[00:00:00] Section: Teaser

[00:00:00] Dr Pragya Agrawal: But a collective anger that we are seeing right now, the simmering, seething anger that we are seeing amongst women everywhere in this world, I think's a fantastic thing. We all need to show that we are not okay with this. We are not going to accept it. And it's okay if we are called hysterical. It's okay if we are called angry. Anger can be a fantastic agent for change, but it also depends on who's allowed to express that anger and whose anger is taken seriously.

[00:00:30] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:31] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:01:04] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:01:05] Anna: Hello, welcome friends to another episode of The Story of Woman. I am filled with hope, frustration, joy, and anger to bring you today's topic of conversation: emotions. You know, those pesky little things that control women and make them do all kinds of crazy things, but have no impact whatsoever on men who can just rationalize all their feelings away.

[00:01:35] Or so that's how the story goes. But of course, in reality, all of us experience the same emotions. It's just that the way we are encouraged or discouraged or sometimes even punished for showing these emotions varies depending on our gender. And also our race and class and other social groupings.

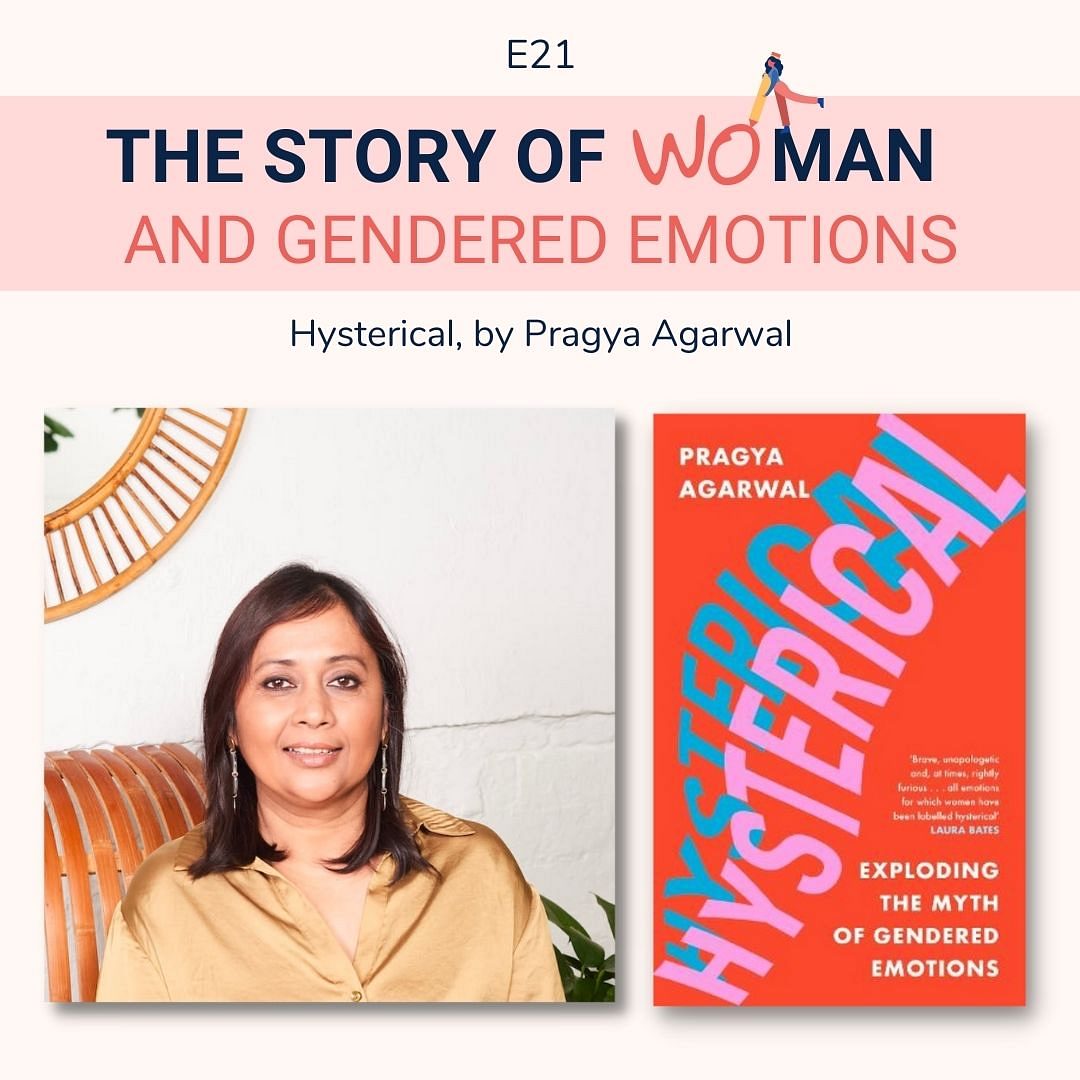

[00:01:57] But my guest today brings all of this to light with her book: Hysterical: Exploding the Myth of Gendered Emotions. I am speaking with Dr. Pragya Agarwal. Pragya is a behavior and data scientist and visiting professor of social inequities and injustice at Loughborough University in the UK.

[00:02:18] She's the founder of a research think tank, The 50% Project, which investigates women's status and rights around the world. Pragya is the award-winning author of Motherhood, Sway, Wish We Knew What to Say, and a book for children about standing up to racism. And her bio goes on. She's a journalist, consultant, speaker, including of two TEDx talks and much more.

[00:02:44] In our conversation today, we get into where exactly these myths come from, why they're so pervasive and problematic, what Pragya's ungendered emotional utopia looks like and how we can get there.

[00:02:57] If you're new to the podcast, welcome, there are a few episodes that might be worth revisiting after this one because the themes we get into in today's episode really overlap.

[00:03:07] For example, in episode three, I speak with neuroscientist Gina Rippon about the myths of the male and female brain. In episodes five and six, I talk to Elinor Cleghorn about the history of hysteria. We trace it all the way back to its origins in ancient Greece. In episode 15, I talk to Virginia Mendez about raising children free from the confines of gender stereotypes, or at least trying to. So if you like today's conversation and wanna hear more along these lines, those are some good places to start.

[00:03:43] And lastly, before I get into the episode, I wanna take a minute to tell you about the newest podcast that I'm obsessed with, it's called the Vocal Fries, and it's all about linguistic discrimination.

[00:03:56] Regular listeners of the podcast will know that many of my conversations include the importance of language and how our words influence our social systems, reinforce all of the phobias, and really shape the way that we operate in the world. Words matter. And Vocal Fries is here to tell you why. Why our language matters and how it's used to reinforce biases and inequities. Or as they so wonderfully put it, they teach you how not to be an asshole about language.

[00:04:30] And we need more people to not be assholes about language. We need more people who say humankind instead of mankind, who understand that using words like bossy and hysterical and hormonal and shrill and sensitive and emotional are not harmless jokes. Words matter. So I am so glad that these two amazing women, Carrie and Megan, are out there chipping away at the linguistic asshole count.

[00:05:01] And they know it's easy to fall into these asshole traps because of how we've grown up with this programming. So they're there to really help with that, with the unlearning and deprogramming, and they do it all with some amazing guests and much needed humor. There's a link in the show notes or search The Vocal Fries wherever you get your podcast.

[00:05:24] A few episodes I'd like to recommend Maintenance Baes where Carrie and Megan speak with the co-host of the podcast Maintenance Phase, and they talk about wellness, diet culture, fatness, and how to not be an asshole to fat. Or the episode with Sarah Marshall, where she talks about bimbos, vocal fries and the word "like", or the episode with Corey Stamper on the history of swearing.

[00:05:52] So there are lots of places that you can start with this podcast and I pretty much guarantee you won't be disappointed. I'll link to all of those favorite episodes in the show notes as well.

[00:06:03] So Pragya and I talked about the impact language has on these gendered emotions as well. It just didn't make it into the final cut because I'm trying hard to keep these episodes to an hour, but it did make it into the bonus Patreon episode. So if you wanna hear how language helps us make sense of emotions, sign up to be a patron of the podcast.

[00:06:25] Also in this Patreon episode is Pragya's concerns and hopes for the emotional technologies of the future. Have you ever wondered why all the Alexas and Siris of the world who we boss around so easily are always female? And yes, we also get into the future of sex robots. So I think this is a bonus episode you're gonna wanna check out. There's a link in the show notes and on the website, but for now, let's hear from Pragya about all these pesky, universally human emotions. Enjoy.

[00:07:04] Section: Episode interview

[00:07:05] Anna: Hi, Pragya. Welcome. Thank you so much for being here today.

[00:07:10] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Thank you so much for having me on, Anna. It's lovely to speak with you.

[00:07:13] Anna: Yeah, you too. I'm really excited to talk with you about your book, Hysterical: Exploding The Myth of Gendered Emotions. And just a warning to everyone listening, this book and this conversation may evoke strong emotions. I know it certainly did for me. But I wanna start with that myth. Can you tell us what exactly is the myth of gendered emotions that you were trying to explode?

[00:07:44] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Yes. So I wanted to, in this book look at the notion that certain emotions are associated with men, are masculine emotions, and I say that in quote marks, and certain are feminine emotions. And I wanted to address that there isn't really a male or a female brain.

[00:08:02] It's not like men and women experience emotions differently. It's that our expression of emotion and the judgment of emotions is different based on our gender identity. There has been a longstanding commit or kind of a perception that women are too much, that they're too emotional. It's very easy to label women uh, sensitive or hysterical, which carries a lot of historical baggage. And so I wanted to explode this notion that women are too emotional, that women are too sensitive. And I wanted to look at history and science of how this myth came about.

[00:08:38] Anna: Mm. I think that, you know, she's too this or she's too, that is just a classic way of describing women, isn't it? And that we should all be on high alert the next time someone qualifies an adjective with too when describing a woman. And yeah, you do a beautiful job of pulling out science and history and all of the context we need to really understand this issue because it's one of these areas that, because these stereotypes are so kind of mainstream and common, we understand them on a superficial level, but you provided that context needed to really understand where does this come from and you know, what's the harm? And you talk about rules and the book, feeling rules and display rules. Can you tell us a bit about those? What do you mean? And can you give us some examples?

[00:09:30] Dr Pragya Agrawal: What do you say about stereotypes is certainly true, but I think when stereotypes become deeply entrenched in society, in our words and in our language and in everyday actions and the way we see things around us and read things, we start assuming that those are the norm and we start comparing everything to it as the norm.

[00:09:49] And anything that doesn't meet the norm becomes an outlier or is marginalized. So we start assuming it is a norm that women feel too much, that women are too emotional, or women are generally hysterical. And so this label becomes associated mostly with women. In terms of rules, rules are these kind of norms that are set in a society.

[00:10:08] So, every workplace, every society, depending on cultural context, have certain kind of impropriety threshold where anything that is above or below it is considered as an outlier. So this become the norm that if showing too much anger or showing too much sadness or not showing enough happiness or not smiling enough, is seen as an outlier and it can be penalized or judged for being outside the norm.

[00:10:34] And so these norms or these display rules become entrenched in our society and we start looking at these norms or we start imbibing them, but also constantly being aware of these norms around us. And we start uh, modulating our emotion or emotional display according to these norms in the society or in workplaces, wherever we are, amongst family, among friends. We become aware of these expectations that are imposed on us according to these rules, and we start suppressing our emotions or exaggerating emotions depending on what is . Expected of us. And everybody edits their emotions we all do that. But through this book, I wanted to show that there are some people who have to do this more than others, and that has a huge mental and physical cost associated with it.

[00:11:22] Anna: Yeah, it becomes a bit of a self-fulfilling cycle, right. And you talk as well about stereotype threat which is, you know, essentially that fear or anxiety of confirming a negative stereotype about your group. So if you're a woman and you need to solve this math problem in class, you're aware that if you don't solve it, you're gonna be reaffirming the stereotype that women are bad at math.

[00:11:47] And it's the same with feelings and emotions, and exactly as you say, that carries such a huge, emotional, psychological toll, all of which we'll get into. But I wanna back up for a second, the story goes that this dichotomy of emotions is just natural, right? Men just happen to be more stoic. Women just happen to be more nurturing. So what is the reality? Are we hardwired to feel a certain way and what would you say to someone that feels quite adamant that, you know, this is, this is just natural and I see it from, uh, kids as young as 3, 4, 5. So surely it must be natural.

[00:12:30] Dr Pragya Agrawal: We start assuming that our behaviors are only a result of our innate hard wiring. And so we start judging or evaluating other people's responses to things and saying that all women are like that, or all men are like that and women are just like this. It's, it's my experience. But I talk in the book about gendered socialization first of all. That research shows that when children are very, very young, just after they're born, there's no difference in how they're expressing their emotions, how much they're expressing their emotions. Yes, there are personality differences, temperamental differences. And that can be innate, but that is not based on a gender of the child.

[00:13:07] That is not just because boys cry less than girls, that they're more stoic, or that girls are just screaming more or, but we know that even from a very young age, because we have got implicit biases as parents and carers, we treat girls and boys differently. We assume different things from them, and we impose these implicit stereotypes that we carry on the children around us. The children we are responsible for.

[00:13:34] Even in the most gender equitable households, research shows that parents use different kind of language with girls and boys. So they might ask girls to be more careful, take less risks or to say be careful or watch out more to girls, while boys are believed or perceived to be wilder or be able to take more risks.

[00:13:52] So they're encouraged to take more risks, be more sporty. They're more permitted to be loud and noisy but girls are supposed to be passive and supposed to be quieter. And this is the kind of assumption that is imposed, a norm that is set in a society according to historical legacy of how gender was defined, how men and female roles were defined or ascertained. And we have taken on these stereotypes and internalized them through the books we've read or the way we've been brought up, or things that we've seen around us. So even in most gender equitable households, we would do that. And I'm quite conscious of my own words and language when I'm doing that with my own children.

[00:14:34] So it is, when we do that, children also take on these stereotypes or these expectations that have been imposed on them, and they start internalizing them in turn. So it becomes like a cycle. And once they become socialized into these expectations, these norms that have set around them, we'd find that by the time the children are 10 or 11 years old, these become quite, what we can call hardwired or deeply embedded into them.

[00:15:01] And so we start assuming that these are just their own temperaments that are innate in them. We also have research, I quote a lot of research in the book, about how when we look at school photographs, we don't see any difference between whether the girls or boys are smiling or not when they're younger, but by the time they're at 11 or 12 or 13 years old, girls are smiling much more than boys because these expectations are imposed on them about that they need to smile to make people comfortable around them. Girls in general are expected to create comfort for around other people, which is also called emotional labor. So we are providing more emotional labor so that people don't feel uncomfortable or inconvenient around us, and we learn to do that.

[00:15:43] We are asked to smile more. Women are asked to smile more. And so, this form of gender socialization, which we see in clothes, which is in books which we see in TV programs or cartoons, or Disney films, become perpetuated or reinforced through children's behavior. We know from neuroscience research that male and female brains are not different. There's no, nothing different about them. It's not like men are from Mars or women are from Venus. That is a myth. So if there's no difference in our brains, then our experience of emotions is not likely to be based in our physiology or our biology. It is according to our social and cultural context.

[00:16:25] Anna: So you're saying we experience emotions the same, but then how we are allowed to express and display those emotions, it goes through this gendered filter based on everything that you've just laid out, how we're raised, all the cues we're taking in from books, movies, all these expectations, and that in turn kind of is where the difference lies and then continues to perpetuate the cycle and so on.

[00:16:51] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Absolutely perfectly. Yes, that's what I'm trying to say. Yes.

[00:16:56] Anna: That's what you did say. Yeah, absolutely. That was what you laid out in the book with ample amount of evidence and, and research. You know, it, it makes so much sense when you look too at the first thing that a baby comes across when they're born, is the colors pink and blue. And is the different types of, whether it's dinosaurs and trucks or barbies and dolls, you know, from the earliest, earliest days. And I had, Gina Rippon on this podcast before, and we talked about how we think babies are these helpless little creatures, but in reality they're like absorbent sponges. So it starts from the earliest days, right, from the time that you're a baby?

[00:17:36] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Yes, absolutely. They are like sponges and that is the perfect word to use, which I was going to say, they are absorbing all this information even when we think they're not, even when we think that they're not taking anything in. We know from developmental psychology research that children as young as six years old can make these distinctions between what is good or what is bad or what is comfortable for them, and they start putting things into boxes and labels.

[00:18:00] And yes, the clothes, I mean, I have such a huge problem with when I go into clothes shops, children as young as, at newborn, they have cuddly toys or soft toys or bunny toys on girls clothes, and there are dirt tracks or tractors and all those construction toys and wild things and adventurous things on boys' clothes.

[00:18:20] And we, we perpetuate that through these things. We also know from developmental psychology research that children, as they're growing older, they're making a sense of their membership groups. So that is how they're making sense of their place in the world of, of their own identities. So as soon as a child starts identifying and saying, I'm a girl, or I'm a boy, they look at other people in their group, in their membership group, to see what kind of behaviors other girls or boys are doing and what I should be doing so that I can be part of this group.

[00:18:52] So if all the girls in the nursery are playing in the kitchen corner and all the boys are playing football outside, then a girl is more likely to conform to what other girls are doing, because that is an expectation. That is something they internalize and that is how these behaviors become embedded. And we start thinking that that is their choice. But a choice are not free of the social and cultural context that they are set in.

[00:19:15] Anna: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that, that freedom of choice. That's a really, really good point. We think that it's a free choice, but exactly as you say, there's so much context that it's not actually the case. So how then do, how do race and class come into play with these rules?

[00:19:35] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Yeah, I think similarly, so in my, one of my earlier books, Wish We Knew What to Say Talking with Children About Race, but also in Sway, I looked at the same rules of developmental psychology, how it applies to race. So race is another form of distinction. Children are making sense of their own place in the world through their own membership, but they're also making sense of the hierarchies that exist in the world through what we see in films.

[00:19:58] So if they're seeing films or Disney films, which only shows blonde hair, blue eye princesses, then they start absorbing this message that, that is the notion of beauty, that that is classical beauty. That's what beautiful is. So they either idolize that or put it on a pedestal and we know several research studies that children as young as three or four years old across the world, not just in the western countries of all ethnicities, choose a blonde hair doll or a white skin doll compared to a darker skin doll, because that's what they have started internalising the message that this is beautiful and this is ideal, as compared to others. There's also obviously a problem of representation. What we don't see, what we don't hear, that is not made visible and so children either from a sense of a kind of a low self-esteem because they don't see themselves represented in media or books around them and they think, I am the outlier, there's nobody like me. Or they start getting a implicit sense of superiority where they assume that that is what normal is, that they start making a sense of what is normal and what is not. They also assign roles to people. So it's kind of a reductive reasoning that children, young children don't have that kind of reasoning where they can make other kind of rational links.

[00:21:18] So they have this kind of reductive reasoning where they, if they see certain ethnicity or skin color, people doing certain jobs in society, like if they're doing more subservient roles or if they've only had a cleaner from a particular ethnicity or skin color, they start assuming that people of certain communities do certain jobs in society and that's how they start labeling people or homogenizing people.

[00:21:41] It's a very simple thing, but I think we have to challenge these all the time because even as something as simple as what my child was saying a few years ago, that boys have short hair and girls have long hair, and it's such a simple thing, but that's how they were making sense of the world.

[00:21:56] They were assigning these kind of labels and stereotypes to be able to make sense of people they meet. And so I had to disrupt that and say, no, actually we can't assume that. We can't just assume those kind of stereotypes. So I think it's, it's up to us to challenge and disrupt those notions when we see them happening in our children.

[00:22:16] Because even we assume children are not noticing, they are doing that, they're always doing that. And class is another form of hierarchy. So how working class, middle class, upper class people react, what children see in films, what kind of roles people see, what kind of stereotypes are assigned to different classes, that can also become embedded in their psyche as well.

[00:22:36] Anna: Yeah. And we'll get into all of the negative impacts here shortly, but I wanna do a bit of a, a history lesson so we know now, you know, they're not hardwired, we have all of these different influences, that help to make emotions gendered, but how did emotions become gendered in the first place?

[00:22:57] Dr Pragya Agrawal: When we look at history, we don't see much mention of emotions in a very explicit manner. We have to understand that for a very long time, emotions are considered inferior to rationality and logic. So it was not considered a serious subject to be studied or talked about. Even in science, even in scientific research, it's only in the last 50, 60 years that we are thinking and talking more about emotions and we are seeing more research in emotions.

[00:23:24] But for a long time it was just considered a soft subject that we don't really need to talk about. If you go back as far back as classical literature and classical art, we see that there were these certain kind of masculine attributes and feminine attributes that were assigned or determined, as I mentioned, rationality and logic was considered superior to emotionality. And men were supposed to be more logical. Men were supposed to be hot blooded as well, so they could handle some of the extreme emotions like anger. That's why it became a masculine. Women were more fragile. Women, women were coldblooded. And so they couldn't handle a lot of the extreme emotions like anger. But there was an inherent paradox because they couldn't handle these extreme emotions like anger and if they were taken over by envy or jealousy, which was a considered a feminine attribute, so it was an inferior attribute, a desire, jealousy, it was always assumed that they would act in a way that was harmful to other people around them. And we have a lot of examples in classical myths like Medusa, who does that, and in other literature as well, in classical literature.

[00:24:29] So these kind of polarized frameworks were set out from all those years ago. And it kept on getting passed on through generations, through different periods of history. And as we move on, we see that women's emotions were always considered a drawback that it was a limitation. Because they couldn't handle their emotions, they didn't have the strength to do that, they were limited or relegated to the domestic domain, not the political domain, not a public facing domain, because they didn't have the rationality or the logic or the strength to be able to handle their emotions and not act out according to their emotions or not act out in jealousy or envy or desire, all those kind of things.

[00:25:09] And so while it was disadvantage women, I think that these kind of gendered emotions also disadvantaged men at the same time, because men were supposed to act in a certain way, which showed that they were strong, that they had courage, that they were always keeping their emotions in. And that's where the notion of suppressing, crying, that boys don't cry, all those kind of stereotypes came about as well.

[00:25:30] And what we are talking about is in terms of toxic masculinity now. So men were not supposed to cry. And so it is often at funerals, they would bring in people to cry for them because they were not supposed show grief. Grief was a inferior emotion.

[00:25:47] Obviously as we talk about men and women, we had to consider intersectionality. So even during those periods, upper class men and women for allowed certain emotions, they could transgress these norms and they were not penalized as much. But within these different intersections, what considered lower class men or men from minority ethnic communities, or lower mid working class women, were not able to transgress some of these norms, they were penalized more for it. But certain emotions were associated with lower classes as well. So things like lower class men would give in more easily to their emotions because they were closer to women in that way because they were inferior within that hierarchy.

[00:26:30] And lower class women were also associated with giving in too much to the emotion. They didn't have the restraint. That was the privilege of upper class women. So within these groups, also, there are hierarchies that have been set up, and we still see that in our current society as well, according to different intersections of race and gender or class.

[00:26:50] Anna: So it goes way back. And, you had a good amount in there about, you know, the overt ways that people were penalized if they didn't follow these rules. And by people, you know, I mean women mostly. So, you had a section in there about witches. You know, I feel like a lot of this all comes back to witches. Can you tell us a bit about the history there and the kind of enforcement of emotional norms that happened in the more overt ways?

[00:27:18] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Yeah, I think the history of witchcraft is the history of gendered emotions, and it's about the suppression of women and their freedom and their autonomy, because what were witches, were the ones who were transgressing these norms that were saying, I do not believe in these restrictions, in these rules that have been set for me. I don't want to behave in this certain way. They were seen as uh, women who were acting out on their desires, so they were not modest or modesty, a very feminine attribute, and they were breaking out of that kind of, boxes that they were supposed to fit into.

[00:27:51] And so the whole idea of which hunt was actually men playing out the power and privilege they had by hunting women who were breaking out of these boxes and punishing them in a sense. But it was also giving message to other women saying, if you do this, this is what happens to you.

[00:28:10] And we also saw that women were reporting other women as well. Of course. And that happens still in our society because women also internalize these messages. And the proximity to patriarch is what gives them power as well. So it is a way of protecting themselves as well. So women were also reporting other women because it was a way of protecting themselves, saving themselves, or keeping themselves safe. And we saw that in England a lot, obviously. Then it went across to America and we saw witch hunts happening there, and they were public facing trials that were happening to give this broader message that everybody has to keep within these norms that were set in these kind of implicit but also explicit norms.

[00:28:52] There were a lot of books at that time coming out with rules for how women should live, how women should behave, how a proper good girl or a good woman should behave. We know about how many of which chance happen in the UK or in England at that time.

[00:29:07] Actually, I looked at how witchcraft still continues in some communities and it is also a way of punishing women. Um, So I looked at India that it happened a few years ago. It's about women who are either widowed or women who don't have a husband who are unmarried. So basically they're shattering the notion that women have to be married, or women need to have children. Women need to be protected by patriarchy to be able to be a valuable member of the society.

[00:29:39] And if they're not, if they're independent, if they're asserting their independence, then there's something wrong with them. And we are still seeing that because we are still seeing all these messages in the media, whereabout that's falling birth rates or that women are not having enough children. And that has got the implicit message associated with it, that childbirth is a way of women to conform to the feminine roles or attributes that were assigned to them. And if they're not doing that, then there is something wrong with them.

[00:30:08] Anna: Hm, uh, yep. That, that is an all too familiar narrative. So I wanna talk a little bit about the impact then, and why all of this matters. So, you've just laid out that clearly, you know, in some of these communities, accusations of witchcraft and punishments for women that leave their boxes is very much alive and well and continuing to happen. So can you tell us about, in addition to that, what the problem with all of these rules and stereotypes are? Why does it all matter?

[00:30:49] Dr Pragya Agrawal: It matters because we are still judging people according to these rules or norms. And we might think we've made a lot of progress, but I think some of these implicit stereotypes and expectations and assumptions are still persisting.

[00:31:02] So let's talk about just about women in politics, for instance. We see this being played out in politics again and again. Women in politics, in leadership positions in particular have to walk a very thin, tricky line where they have to conform to certain attributes to be seen as a good leader. And that is because for a very long time, the notion of leader was associated with being a man with masculine attributes like toughness or courage or stoicicity or resilience. All those restrained, emotional restrained. And so women were not considered to be good leaders. And that still happens. Women are not seen to be authoritative or aggressive enough, or self-motivated enough to be good leaders.

[00:31:41] They have feminine attributes associated with them, like warmth and likability or collaborative, all those kind of things that we still see a very gendered way that women and men are described in workplaces or even when recommendation letters are given in the same team. So, women have to walk this thin line where they have to show some of these masculine attributes in order to be seen as a good leader. So they have to be aggressive, occasionally authoritative, assertive, tough, emotionally restrained, not show anger or too much emotion because any expression of emotion is suddenly seen as they're too feminine and not a good leader, not fit for this role.

[00:32:22] But they can't move away too much from the feminine attributes either. So they still have to be warm and likable because they're penalized for not being that as well. They're very quickly called bossy or bitchy, and as well and, and shrill if they ever break out of those kind of norms. So it's a really thin, tricky line for women to follow.

[00:32:43] We saw that with Hillary Clinton. I give an example of Hillary Clinton and a number of other women in politics. She has herself talked about that from a very young age, she learned that she shouldn't show any anger or emotion because it could count against her. So during the whole election presidential campaign, there were lots of occasions when she was called, ice cold or that she didn't have any warmth or empathy. But she was also called angry at times.

[00:33:09] Whenever she occasionally raised her voice in her debate when other candidates were doing the same. She was the one judged for it negatively. And then obviously she lost, and when there was the survey happened later, both men and women in this huge survey in the us admitted that they thought that she was the more qualified candidate out of the two who won, which obviously she was. Whatever your

[00:33:35] Anna: Shocking.

[00:33:36] Dr Pragya Agrawal: your political affiliations or beliefs might be, but, but she, they didn't consider likable enough or empathetic enough to be a good president. And that is such a strange paradox or this kind of thin, tricky line that women have to navigate in politics, but because they're still judged by these archaic rules and tropes that have been set out in society, and that's just one example.

[00:34:01] In medical domain, this plays out in form of how women's pain is underestimated and, and women are not diagnosed and treated as quickly. We know from the recent NHS research actually that men get diagnosed and treated for the same conditions four years younger than women.

[00:34:17] And women are seen or perceived to be overestimating their pain. So that means that they're not given the same treatment for the same condition, while men are actually believed or perceived to be underestimating their pain because they still believe that men are more reticent or restrained or stoic. So that means that they're underestimating their pain.

[00:34:38] And this plays out again and again in medical domain. There's such a huge disadvantage for women, in terms of how women's conditions are perceived, how things like endometriosis is not treated or we don't have enough treatment for that. How it's often said, it's in your head, how it's associated with psychosomatic causes. How women are not given the right support or treatment.

[00:35:04] I know from personal experience, I know from testimonies of women, I know from huge amounts of research. Within this, obviously there are intersections. We know that Black women die four times more in my childbirth and maternity. We know that certain ethnicities face more racism, so there's intersection of that as well.

[00:35:23] But basically it's, these are just example of two domains in medical domain and politics. But this is in all sorts of areas. This notion that women are more emotional or women are too emotional, has a huge disadvantage for women.

[00:35:39] Anna: Huge disadvantage. And yeah, like you said, that's only two, two examples, and you can apply that to every industry, every facet of life, and even just like at a basic level, you know, the way I see it is like, as you say, all of us humans, we experience emotions the same, but all of these emotions get split up into two buckets that each gender can access one of, but neither of which can access both of, so no one can express the full range of human emotions and feelings and, you know, what does that do kind of psychologically, emotionally, what's the kind of mental toll that that takes on a person to have to regulate and suppress their emotions?

[00:36:30] Dr Pragya Agrawal: When we are constantly modulating our emotions or suppressing our emotional expression, we are juggling this all the time. We are basically being hyper aware, first of all. So it's a form of stereotype threat, but being hyper aware is that we are constantly judging other people's emotions and modulating our emotions according to their own emotional discomfort.

[00:36:52] Because for some reason women tend to internalize this more that they are responsible for other people's comfort. So they tend to do this juggling act more. And when we are being hyper aware, you're always on high alert and that creates stress and that creates anxiety because you are always wondering, what is the threshold here? How am I supposed to be? What are the expectations here? What are the norms here? You're constantly monitoring things and if you don't, you know that you're fearful of being penalized or judged for it, or punished even for it. And it has huge cost. We know that angry women are judged differently to angry men, even in workplace situations.

[00:37:32] So there was this experiment done where it showed that when a woman is perceived to be angry, it is attributed to her personality. She's just an angry person. While for a man, it is attributed to circumstance. He's having a bad day. So there are more excuses can be made for it. It's attributed to other causes besides his personality.

[00:37:51] But also in workplace, people admitted that they would pay an angry women four times less than an angry man, at least four times, but significantly less than an angry man. So it has a huge cost. And so women are mostly aware of this, often aware of this, the cost that it would incur if they go outside these norms.

[00:38:09] And psychological research shows that it has consequences such as anxiety and depression and insomnia because you're constantly carrying this weight of expectations around with you. And of course, as we say, there are other costs associated, direct and indirect in terms of medical diagnosis and treatment, in terms of how women's depression and anxiety is treated, how they're believed or not believed, how their testimonies are believed.

[00:38:34] So even in jury situations, women are not often believed. They have to modulate their emotions in order to be believed. We saw that with the recent Amber Heard, Johnny Depp case. And I am not going to comment on what was right and what was wrong, cuz I don't know what happened inside a relationship.

[00:38:51] But all I know is that the way that Amber Heard was judged for her expression of emotions was different to how Johnny Depp was judged. If she was a trauma survivor, she was expected to act in a certain way. She was expected to act like a victim. She was expected to be passive or sad, crying all the time just because she showed anger, she was judged for it.

[00:39:13] And we know that after the trial, one of the jury members even said anonymously that she, one moment she was crying, another moment she was angry or shouting, and so we could not believe her. So women's testimonies are not believed and that has a huge mental, emotional cost as well. And we know that emotional cost is very much linked to physical discomfort, but also other forms of physical illnesses as well. Yeah. So those are some of the mental and physical impacts.

[00:39:42] Anna: Yeah. And you, you talk about anger there and I just keep thinking too, and I, you know, you lay it out in the book is like, how important anger is, not just in terms of how unhealthy it is to suppress it, but in the terms of the fight for equality and change and progress, anger is, is vital. So is there anything you wanna add to that point? You know, you talked about anger as this agentic reaction and I thought that was a really good way of laying it out and really understanding what anger can do. Can you explain what, that means?

[00:40:16] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Anger is an agentic reaction because it creates change. It is an agent for change. It mobilizes change. When we are angry at something, that means that we don't accept the status quo. And there are lots of reasons to be angry about right now. Women's reproductive rights are under threat, women's rights are going backwards everywhere.

[00:40:35] And we are seeing collective anger, but we still know that when women get angry on social media or in real life, they are judged for it, especially on social media. You're not allowed to get angry because you'll treat like an angry person.

[00:40:50] But the problem is that when men get angry, they're often taken seriously. But when women get angry, because it's attributed to their personality, it can be used calling them hysterical or angry or even fiery I think a word that's not used for men, silences them. It is used to shut down their very valid opinions. And expressions of displeasure or the fact that they want change right now, that this is something not good.

[00:41:20] But a collective anger that we are seeing right now, the simmering, seething anger that we are seeing amongst women everywhere in this world, I think's a fantastic thing right now. I think it is great because we all need that. We all need to show that we are not okay with this. We are not going to accept it just like this. And it's okay if we are called hysterical. It's okay if we are called angry and we are not just getting things out of perspective. This is as bad as it gets and we are not going to accept it. So I think anger can be a fantastic agent for change, but it also depends on who's allowed to express that anger and whose anger is taken seriously.

[00:42:05] Anna: Definitely. And in addition to being on high alert, when you hear a woman called "too" something too aggressive, too emotional, I also think we need to be high alert of how people respond when a woman is angry. Exactly as you say, it's attributed to her personality or you know, getting her to calm down, her mental stability instead of looking at, Oh, what is she angry about?

[00:42:29] You know, we don't, we don't listen and look at the thing that she's angry about. We look at her. Whereas for men, we look at the thing that they're angry about, typically, so..

[00:42:38] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Yeah, recently, I mean, I know this happened so much on social media recently we were talking about something and I expressed, and it was not even an angry tweet, but there was quite a few men who came and said, do you always have to get your nickers in a twist? And that was just another way of silencing me because you immediately feel like,

[00:42:58] Anna: Yeah.

[00:42:59] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Oh gosh, have I been too much? Have I said too much? And that is, that is how people can be shut down.

[00:43:08] Anna: Absolutely. Yep. And not, they're not addressing what you said on Twitter. They're just addressing your emotion of anger. And you mentioned this before, but I think it's an important point to kind of circle back to, and that's emotional labor. Can you tell us what that is and how that plays into all of this?

[00:43:30] Dr Pragya Agrawal: So emotional labor is modulating our emotions for the comfort of others. That means that we are making changes to our emotional expression or even to the way we are experiencing emotion. We are putting a barrier to experiencing certain emotions because we think that it's going to make other people uncomfortable.

[00:43:49] And so the original definition of emotional labor, it was sort of how women do this labor to create comfort with others. It doesn't necessarily have to do with emotions. It's like if I take on a lot of mental load. So the notion of mental load is very much linked to emotional labor. So even if I'm feeling angry about something, I cannot show that anger because I'm creating discomfort for people around me. So if I'm in a meeting and I'm getting really angry, I can't show that anger cuz other people are going to get really uncomfortable about it. So that's sort of a form of emotional labor.

[00:44:24] In a workplace situation, that happens quite a lot because again, women are supposed to be warm and nurturing. So they are assigned more roles, which have to do with creating comfort for other people at the cost of their own comfort. So, for instance, women are given more mentoring roles, like organizational roles, like organizing an event in the workplace or doing something that is unpaid, invisible labor, that is not paid, that then nobody thinks incurs a huge amount of time, but they often have to do it.

[00:44:58] They are better at organizing. You are just good at it. You're just better at it is often said to women. And so they take on those roles that I should be okay with it and I shouldn't get stressed because I am a woman and I should be able to manage. And a lot of things. Women are better multitaskers is another thing, a myth that has been perpetuated so much, which really disadvantages women because women start believing it. And women think, I can do it all. I can do it all really well. And no, nobody can do it all and you shouldn't have to do it all.

[00:45:30] At home, the notion of mental load happens because even if in the most gender equitable households, women often take on the responsibility of organizing people's timetables, children's schedule, who's supposed to get presents? What is the Christmas shopping list? What is the Christmas present list? Who's wants what presents? Who would like what? How do I organize a holiday? All those kind of things that seem like they just happen automatically on their own without anybody doing it. And so that is an invisible, unpaid labor.

[00:46:01] But it's also linked to how certain communities or minority ethnic communities, are expected to provide more emotional labor or mental labor for comfort of other people. And again, that's linked very much to societal hierarchies. Recently I went to California and all the salons there, nail salons, are run by women from East Asian origin, like China and Japan, Vietnam, and that kind of creates this kind of myth that women from that community are better at providing this kind of emotional or mental support to other women at the cost of their own because they have to modulate their emotional expression because they're in the service industry. So anybody in the service industry like airplane attendants, or anybody who's providing this service, like in the restaurants, they have to moderate their emotional expression. So it is a form of emotional labor, but as I said, it often falls to women more in workplaces and in the home organization because of this traditional feminine attribute, or that women are just better at it.

[00:47:04] Overdub: “And now for: “men are losers too”... in gender inequality of course. These are not "women's" issues, these are everyone's issues, because as long as women are held back from their full potential, so are we all.”

[00:47:19] Anna: Switching gears slightly, well, not really switching gears, but on the flip side, you mentioned in the beginning, that boys are taught from a young age that crying is not okay, that sadness is not okay, but that anger is, and that they are allowed to access other emotions. But a recurring section of this podcast is talking about everything that men stand to gain in a more gender equal world. So I'd love to know from your perspective, how do all of these rules impact men and what do they stand to gain by helping to shift and un gender all of these emotions?

[00:47:56] Dr Pragya Agrawal: I think any form of equality is going to be good for everybody, for everybody in the society. And although there's a slight initial discomfort because it's changing the status quo, and whenever we flip these kind of norms, um, we incur some kind of cognitive load or cognitive discomfort. And we always think this is not right, this is not correct because we are flipping the status quo.

[00:48:18] But it is going to be good for men because men are also boxed in through these gendered emotions, these notions that men have to be stoic, men have to be strong, men have to can't cry. And that also pushes men into certain templates and boxes as well. And men feel the pressure to act like a typical man.

[00:48:39] What does being manly mean? And because we are having these conversations of gender equality, a lot of men are feeling quite insecure about the manliness, about how to be a man. And I think we need to break out of these binary divides about trying to be a man or trying to be a woman in their certain roles that we have to be played to, that we just have to play to our own strengths, and we have to be the best humans that we can be.

[00:49:03] I think that is the most important thing. For instance, yes, crying is not perceived to be good in men. So, which means there's a rise of depression and suicides in men as well. For a very long time, men were not able to express the mental health concerns. We didn't have a conversation around it. And still, I think even though men's crying has become a bit more normalized, that especially in certain domains like sportsmen can cry after they've won, in particular because they have demonstrated that masculinity or aggressiveness or authority in winning a competition like tennis players, they can show grief, you saw Roger Federer crying recently when he retired, or when Nadal crying and all those kind of things are breaking some of these norms.

[00:49:47] But then we also have to think about which men are allowed to do that. It's, again, there's intersectionality within it that there's certain men are allowed to transcribe these norms and in certain conditions, which means that they are also being judged for it. In sports, for instance, it's still this notion of toxic masculinity, very much perpetuated, especially in football like rugby or football or soccer, that men should not cry or men should not weep, they shouldn't show any weakness. So I think any sort of these kind of stereotypes box men in as well, they have to conform to certain rules which can disadvantage some men more than others.

[00:50:29] Anna: Absolutely impacts us all. All right, so looking forward, what do you think a future where emotions are ungendered looks like?

[00:50:40] Dr Pragya Agrawal: It's my vision of an emotional utopia where, where all of us are free to express our emotions in the way that we want. So it's not according to whether I'm a man or a woman, or a trans man or a trans woman or, or gender nonconforming or whatever our identities is. We have to remember that we should be able to experience the whole range of emotions, not according to other people's expectations and these norms that are set in society.

[00:51:09] I also want us to challenge these assumptions more, not just in others, but in ourselves as well. I think because all of us internalize these assumptions in norm sometimes, and we don't inspect them, we don't reflect on them continually. And I also want a world where, both men and women are allowed to express all sorts of emotions without any kind of negativity or positivity assigned to any emotional outburst.

[00:51:36] And where certain emotions, the negativity associated with certain emotions, like anger for instance, is flipped. So that we think of it as an agentic emotion. And we think about how we mobilize some of our emotional experiences into change if we need to. What do we do to create the change that we need to make it better for us. Because emotional expression, or experience, is not enough, we should be able to change things as well. So first step is to be able to experience the emotions and express it, but then we have need to have the resources and the ability and the frameworks to be able to make those changes as well.

[00:52:15] Anna: So do you think this utopia is ever gonna happen?

[00:52:18] Dr Pragya Agrawal: I'm very optimistic. , I keep hoping.

[00:52:22] Anna: Good, good.

[00:52:22] Dr Pragya Agrawal: One time.

[00:52:24] Anna: One step at a time. So what, um, what advice or tips or what would you say to people who are still, you know, were still navigating this highly gendered world, so you mentioned paying attention to how we are experiencing and expressing our emotions, being more self-aware, but any other advice or, or tips you would have for women or men for navigating this gendered world?

[00:52:49] Dr Pragya Agrawal: I think understanding that we all have some of these implicit stereotypes embedded in us is a really good start. It's acknowledging that, I think is the first step because, um, these cognitive shortcuts exist to help us navigate the world, but they can also be discriminatory because we made sense of this world to the world we have navigated, and that means that we just accepted that this is the way it is.

[00:53:14] There's also a resistance to changing things as they are. This is the resistance to status quo, and that's also cognitive shortcut in our brains. We are resistance change because our brain has to do extra work and our brains are lazy really. So I think acknowledging them and accepting that this is going to happen, there'll be some initial discomfort and it's okay to sit with the discomfort.

[00:53:37] If we don't sit with the discomfort, we don't create change. I think that's really, really important for us to think. . And also, I always say this, but I think it's a really good thing for me personally to remember and for other people that when we think about gendered language or our impact of our actions, which might be gendered, we need to focus more on the impact it has rather than our intent.

[00:54:01] So our intent might not be to offend or to be offensive or to be biased or sexist or whatever, but if that is the impact that's having in society or in an individual, then we need to change that behavior or need to think about how we can change it. And then ultimately it's our responsibility to educate ourselves. There's a lot of resources out here. Um, this podcast is a good start and there are lots of...

[00:54:25] Anna: Thank you.

[00:54:27] Dr Pragya Agrawal: um, and people have an opportunity to educate ourselves and I think it's not just wokism and using work as a negative term, I think is, is a, is the first step not to do that. But it's not just that, it's actually has real concrete impact on people's lives. So I think it's a responsibility to create a better world for everybody.

[00:54:49] Anna: Amen. Absolutely. All right. Then, if, people take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:55:00] Dr Pragya Agrawal: That all emotions are valid. That the fact that we feel that we share and express our emotions is what makes us human.

[00:55:09] Anna: Love it.

[00:55:11] Overdub: And now for: the “feminism gets a bad wrap because the narrative has been just a bit one-sided" corner.

[00:55:19] Anna: All right. And now for some rapid fire questions to wrap up. These are questions I ask every guest at the end. What does feminism mean to you?

[00:55:30] Dr Pragya Agrawal: My feminism is always intersectional because we can't talk about equality without thinking about the stratified layers within the various groups. But I also think about what Audrey Lord said, a masters tool will never dismantle the master's house and how we have to first break out of these systems of oppression in order to actually create any kind of meaningful change and achieve true equality for all.

[00:56:01] Anna: Wonderful. And what is one of your earliest memories of gender? A time when you realized the world didn't treat girls and boys the same.

[00:56:11] Dr Pragya Agrawal: I wrote a lot about this in my book, Motherhood. I think I grew up in India where this became quite evident quite early on. So my first memory is that when my youngest sister was born and we were three sisters, so she was the third, and in the society where everybody craved a son, my father distributed sweets in the hospital when she was born and I noticed that people were quite shocked and they were expressing sympathy when she was born rather than delight and happiness. I think that was the first time it really struck me about how girls and boys were really treated differently.

[00:56:49] Anna: Wow. Yeah, that's quite a memory early on as well. And what is the story of woman to you?

[00:56:57] Dr Pragya Agrawal: It is a big one. It's a big one. I mean, as a story of woman, as a story of patriarchy really, isn't it? It's the story of how patriarchy came established, and it just perpetuates and we accept it as the norm. And unless we really dismantle that, we cannot really change the narrative or the story of woman.

[00:57:17] Anna: A big one, but a great answer, and a couple more, uh, what are you reading right now? reading right now?

[00:57:24] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Uh, my attention span has been shattered through the pandemic and while writing my books, I read mostly related to the books, but I read recently, I went to the US for some work and on the way there I read Sorrow and Bliss by Mag Mason, which was fantastic. It was really good. There was so much in it, which kind of normalized introversion and mental health and the way we engage with the world. I also read, recently a proof or sent to me of, a Horse by Night by Amina Kane, and I think I'm getting that right. It is a fantastic book. It's very difficult to describe it, but I just absolutely loved it.

[00:58:03] Anna: Wonderful. And do you have a book that you would recommend to our listeners? A favorite or one that sticks out? Another tough

[00:58:14] Dr Pragya Agrawal: My mind just goes blank whenever people ask because it changes day by day, can I just say The Velveteen Rabbit? Because I really love book.

[00:58:24] Anna: Of course you can.

[00:58:26] Dr Pragya Agrawal: I, I, I mentioned it again in my book, Motherhood, and it's the first book that I bought for my twins when they were born. I think it's such a beautiful book about how we are made real by love.

[00:58:39] Anna: Oh, love it. Love it. And your, your book Hysterical obviously just came out quite recently, but is there anything that you're working on right now that you would like to share with our listeners?

[00:58:50] Dr Pragya Agrawal: Um, Um, I'm working on bits and bobs, a few things. In the meantime, since I finished working on this book early this year, I've been writing a lot of short pieces. I wrote a piece, couple of pieces last year, which were published this year. So one of them has been published in an online magazine, thing called Below Herb Review, which is a slide departure from my usual work.

[00:59:11] It is a nature piece, but India, Scotland, and it's very culturally specific because we often see nature writing by certain kinds of people. So I wanted to disrupt that narrative. I also wrote, something called Mother Tongue, which was published online in the Florida Review. It's about language and it's about the language we want to pass on and it's a very personal essay. So that's the couple of things that have come out recently.

[00:59:38] Anna: Lovely. And, where can we find you? So we can find some of these writings and, and see what you're up to?

[00:59:44] And

[00:59:44] Dr Pragya Agrawal: My website is very simple, drpragyaagrawal.com. It's got information on the books and it needs to be updated, but it's got all the upcoming events and recent events and how to contact me through the website. And I'm on Twitter and Instagram as DrPragyaAgrawal

[01:00:04] Anna: Lovely, and that will all be in the show notes as well. So Great. Thank you so much for your time today. Joy has been the main emotion I've had speaking with you, though of course, you know, maybe a bit of anger as well, but mostly joy. So thank you so much.

[01:00:21] Dr Pragya Agrawal: It's been an absolute pleasure. Thank you so It's been an absolute pleasure. Thank you so much for speaking with me.

[01:00:26] Overdub: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation... so if you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes!

[01:00:45] You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, become a patreon for access to bonus interviews and content, buy me a... metaphorical coffee which helps with production funds, or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

[01:01:20] Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of our story to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring