[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello and welcome to season two of The Story of Woman. In today’s world, it can feel like change is happening, but only in the wrong direction. While we agree there’s still a lot of work to do, we’re reframing that story.

[00:00:17] Overdub: I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein and each episode of this season I’ll be exploring how women make change happen from those at the top helping to drive it. We’ll look at where we are on this long march to equality, what lies ahead, and how important you are in the fight.

[00:00:38] Overdub: This isn’t a story of a world that’s doomed to oppress women forever. This is a story of an opportunity to grow stronger than ever before. Exactly as womankind has always done.

[00:00:50] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:52] Anna Stoecklein: Hello and welcome back. Thank you so much for being here, as always. I'm really [00:01:00] excited to dive into today's topic because it's not one we've explored on the podcast before and it's a topic very close to my heart. And that topic is sports.

[00:01:11] Anna Stoecklein: I played competitive sports basically from the time that I could walk, and they had a huge impact on my life and who I am today. There's all the classic life lessons like teamwork, confidence, competitiveness, overcoming losses, but also really just having a way to use my body in a non sexualized way that made me feel physically powerful. I hadn't realized how important that was at the time, but for a teenage girl going through puberty and entering into this world that is constantly sexualizing her, that was hugely important.

[00:01:50] Anna Stoecklein: But unfortunately back then, and even still today, girls drop out of sports at alarming rates once they hit puberty, and [00:02:00] female athletes suffer from injury, eating disorders, and mental health struggles, that can all pretty much be attributed to a system that was not designed for them.

[00:02:11] Anna Stoecklein: Yes, the story you'll hear today is a familiar story. Like everything else, yes, we have come a long way in terms of women and girls participation in sports, but the system itself was originally designed for men, for male athletes and male spectators. And just like every other system in institution, we can see the repercussions of this fact still today.

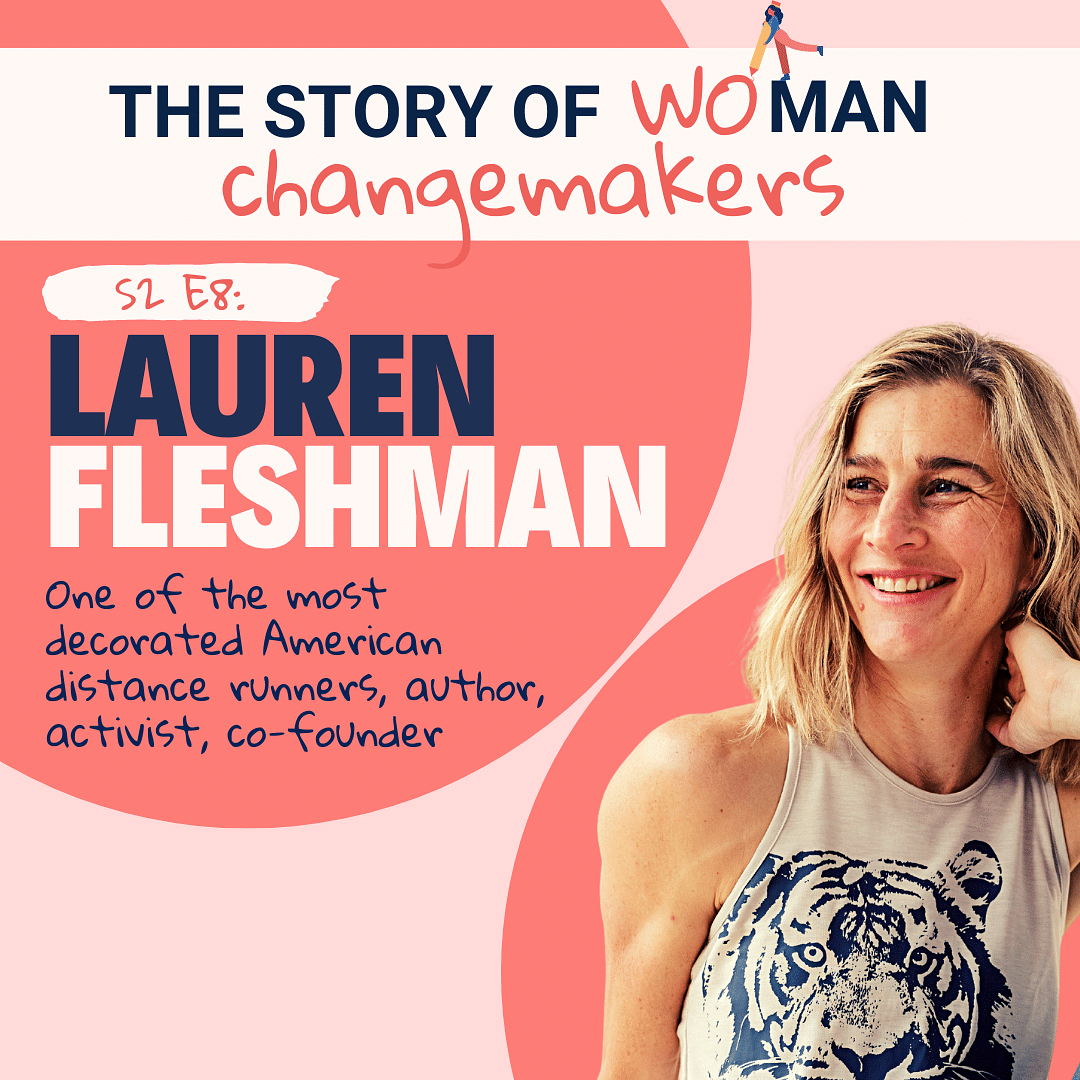

[00:02:36] Anna Stoecklein: So my guest today is raising awareness of this issue and leading the fight for change. Lauren Fleshman is one of the most decorated American distance runners of all time, having won five NCAA championships at Stanford and two national championships as a professional.

[00:02:52] Anna Stoecklein: She's the author of Good for a Girl, which is a phenomenal read that's about her personal journey, but it's also filled with [00:03:00] research about all the problems we're gonna be discussing today. You know, the whole not designed for female bodies thing. She dives into that and provides personal anecdotes as well as research, and it's just a really compelling read for people of all genders and of all ages. And whether you're into sports or not.

[00:03:23] Anna Stoecklein: Her writing has appeared in the New York Times and Runners World, and she's also the brand strategy advisor for Osielle, a fitness apparel company for women, and the co-founder of Picky Bars, which is a natural food company.

[00:03:36] Anna Stoecklein: We're gonna get into all the ways sports has been failing women and girls, but we'll also talk about the progress that's been made and the hope that Lauren has for the future. So that's not all doom and gloom.

[00:03:48] Anna Stoecklein: I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did, and if you did, please feel free to share it. But for now, please sit back and enjoy my conversation [00:04:00] with Lauren Fleshman.

[00:04:01] Section: Episode

[00:04:01] Anna Stoecklein: Hi, Lauren, welcome. Thank you so much for being here today.

[00:04:05] Lauren Fleshman: Thanks for having me.

[00:04:06] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. I'm really excited to have this conversation with you and there's quite a lot that I wanna get into, and we're gonna talk about all of the problems that exist. But before we get into that, I really wanna talk about why everything that we're gonna be speaking about matters, why sports matter. So I was hoping you could tell us a little bit about what sports at their best can add to women's lives, some of the types of benefits that you personally have experienced in all of your years as a runner?

[00:04:36] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, I mean, the benefits are numerous, which makes sense why women fought so hard to have access to them when we were being denied access in meaningful ways.

[00:04:47] Lauren Fleshman: So I guess the benefits for me are probably similar to the benefits of most people. I think it's like a chance to move my body. I don't have a job that requires me to move my body otherwise. It creates like a [00:05:00] structure for a healthy lifestyle. It creates community. It provides this arena to master different types of techniques and skills with your body.

[00:05:10] Lauren Fleshman: That is an inherently rewarding experience to get better at things. And then community collaboration, cooperation, different sort of energy of shared passion that is a lot more amplified than a lot of us get in our daily life.

[00:05:26] Anna Stoecklein: The list just goes on. And for me, as someone who has, I'm not gonna compare myself to you, but who has played sports most of her life, there is just something about them that makes you feel powerful. It helps to build your confidence. And that's so important for women especially, but also for young girls as they're beginning to navigate the world that begins telling them or continues to tell them about where they belong and how it's not necessarily in positions of power.

[00:05:55] Lauren Fleshman: Absolutely. And very early on in a girl's life, pretty early, actually, with my [00:06:00] daughter, it was two, you begin to learn that the way you are seen by others is noticed and commented on. On my son, no one ever commented on his outfits. And my daughter pretty much instantaneously and has learned right away that what she wears will create some sort of response in her world. And then sports is this chance, theoretically, to use our bodies in a way that is not meant to be for anyone else's benefit. It's purely about using our bodies in powerful ways.

[00:06:31] Lauren Fleshman: Success really requires un self-consciousness. So learning to tune out those other voices and focus on what you can do in your body that day, and to see the women around you, on your team, as more than their appearance, which you get a bunch of women out at brunch and they generally are commenting on each other's outfits or haircuts or whatever it is, part of our way we've been taught to interact.

[00:06:54] Lauren Fleshman: Sports is like, let's get down to it. How are you kicking that ball? How are you doing the thing that you're supposed to be doing for the group [00:07:00] and being in awe of each other's skills, right? I just love that feeling on teams growing up, softball and running, of seeing what my teammates could do and just that, wow, like superhero power of seeing them express themselves physically.

[00:07:14] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. It's incredible. So many, many benefits for the individual and for the collective as well. I'm wondering sports is one of the largest institutions in our culture, what role do you see sports playing in the bigger picture of equality?

[00:07:30] Lauren Fleshman: Oh, I mean, it absolutely should be all the things that we say it is, which is this space that's a safe space that women and girls can go to, to use their body in non sexualized ways, powerful ways, develop literal strength as well as emotional strength and psychological strength.

[00:07:48] Lauren Fleshman: And then that space should prepare us to be more resilient and robust in the rest of life and the world. It's a critical institution, but the institution of sports isn't recognizing [00:08:00] that female bodies experience sports in a different way through puberty, and by ignoring those differences, we are blunting the promise of sports for women and actually flipping it the other way and creating harm in a lot of cases.

[00:08:11] Anna Stoecklein: Hmm. All right. So let's get into that. Its clearly important for a multitude of reasons. And as you alluded to, women have fought long and hard just to be able to start playing, but unfortunately, that's not the end of the story.

[00:08:27] Anna Stoecklein: So just a little more background, and a lot of this came from your book, Good For a Girl, which is fantastic and I highly recommend everyone reads.

[00:08:36] Anna Stoecklein: But in 1971, there were fewer than 300,000 girls that played high school sports compared to 3.6 million boys. And then Title IX was passed in 1972, which was the civil rights law in the US that prohibits sex-based discrimination in schools. So from there we start to see women and girls start competing and the numbers start to even [00:09:00] out.

[00:09:00] Anna Stoecklein: But that's not the end of the story exactly, as you've alluded to, because like everything else in the world, the system itself was designed for men, both as athletes and spectators. So I'd love to have you tell us, Lauren, what happens when you take a system that's designed for men and you try to fit all the women into that? Can you kind of give us an overview of the problem with our current sports system?

[00:09:26] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, sure. I think that it was built around, at least the segments of sports we invest the most in, like Title IX applies to high schools and colleges. It's federally funded institutions. It doesn't apply to professional sports, so there's no mandate that equal professional sports opportunities be provided for women and men, but public schools and high school university, you have to, or you're not compliant with the law. You have to provide equal opportunities.

[00:09:53] Lauren Fleshman: We still aren't, we're still not fully compliant. I think we're about 90% compliant in the United States, but those [00:10:00] 10% aren't spread out evenly around the country. That 10% of non-compliance schools are concentrated in communities of color in the south. In some cases, four out of five schools in an area will not have compliance. So we definitely still have a problem with the basics.

[00:10:13] Lauren Fleshman: But even if you assume we're in an area where access is the same, we're getting access to the system built around the male body, around male norms, around male physiology. So ages 12 to 22, pretty much covers middle school through college, and the male body is going through a type of puberty that is aligned with consistent improvement. Work harder, get better, work harder, get better, like that's the way testosterone works. That's the way the type of sex specific changes related to testosterone work.

[00:10:43] Lauren Fleshman: Female bodies go through a totally different experience. We have tissue that's being invested in in our bodies during puberty that is not immediately beneficial to sports performance and at first it actually can make us plateau in performance or even get a little bit worse for a short period of time because we have [00:11:00] higher body fat percentage, we have breasts and hips, and a change in our physics, our very physics and biomechanics that takes some getting used to.

[00:11:07] Lauren Fleshman: But, if we're just given the time to make those adjustments and remain healthy through that transition and encouraged and still love sport, if we can get through that little period of time supported, then our bodies peak much later and we can expect a second impressive rise to get to our strongest, most powerful self in our mid to late twenties and beyond.

[00:11:28] Lauren Fleshman: And we're seeing that. We're seeing that in sports now, that we have huge numbers of recreational participants, especially in the sport of running, which is so popular globally. We see women having second and third waves of improvement just shocking themselves, well into their forties of what they're capable of doing when they may have been taught to give up on themselves in high school or college, when their body was going through that plateau and nobody around them could tell them, hey, this is normal and good, you're perfectly on time.

[00:11:56] Lauren Fleshman: But that's not how we treat it. In our culture, we treat female puberty [00:12:00] like it's a death sentence, a career ender, an indication of what an athlete will be able to do long term, and so we are drawing conclusions from a very sensitive time in their life. I've thought of this analogy recently, it would be like taking 13 year old boys that wanna sing and interviewing them and having them do a performance at age 13, right when their voices are cracking the most and then making a determination on what their future in music is based on that year.

[00:12:27] Lauren Fleshman: We would never do that because we understand that this is part of male development and it's normal and that it isn't indicative of what's to come later. And we need to do something similar with understanding female puberty and our development.

[00:12:40] Lauren Fleshman: Culturally, we are just not studying it. I mean, the lack of research, it doesn't exist. It's most female experiences that differ from men are grossly under-researched, stigmatized to talk about, essentially invisible.

[00:12:53] Lauren Fleshman: And you said before we, you know, we were chatting right before this about how your own experience, looking back after reading my [00:13:00] book was like, oh, that's what was going on.

[00:13:02] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, absolutely. I had no idea about any of this, and you helped explain the past two decades of my athletic life in your book. So I mean, how well known is this? You're obviously starting the conversation, getting it going, but has it been studied at all? Has it been researched?

[00:13:22] Lauren Fleshman: The thing of this idea, I call it the female performance wave, in my book, this concept of it's a different path and linear improvement, than all of the sports motivational wisdom we hear, like you get out what you put in hard work equals results. Like all these things of just like one plus one equals two. And that's just not how it works for the female body during development. One plus one does not equal two every single time. You can work harder and get slower for a period of time, and that's normal.

[00:13:48] Lauren Fleshman: And so yeah, I think that I was looking everywhere for a term. Where is the body of research that falls under this term where everybody's putting these things together in one place and it does [00:14:00] not exist.

[00:14:00] Lauren Fleshman: And so I just took a crack at naming it something. But what does exist is you can see improvement in female athletes versus male athletes has been well documented over time. We see that there's a divergence at age 12 and a half. Before age 12 and a half, female male bodies perform the same. There's no sex-based differences in performance, girls can hold age group records. But once puberty starts, the male curve starts to be steeper in improvement, so they're getting more juice out of every squeeze between the ages 12 and a half and 20.

[00:14:32] Lauren Fleshman: And female athletes are improving overall as a group, but the individuals within that group are experiencing plateaus and dips. But as a group, over time, we do get better, but we get better barely at ages 16 and 17. I think it was like less than 2% improvement for 16 and 17 year olds per year overall as a group. Whereas male athletes are still improving three and a half, 4% per year at that point, which feels noticeable [00:15:00] and 1% feels pretty much like being stuck in place.

[00:15:02] Lauren Fleshman: So we know these things. They're in the data, but we aren't connecting them to a larger cultural experience, physical, physiological, cuz it all plays in together.

[00:15:12] Anna Stoecklein: I see. Yeah. I mean, naming it is so important. If all the data is there, but if nobody's doing anything with it or like you said, connecting it. So naming it crucial.

[00:15:21] Lauren Fleshman: I'm calling it the female performance wave because it comes in, goes down, and then it comes back up. And it can keep going. If you have a baby, pregnancy, you'll have another one of those waves, and that's the inherent experience to female bodied people. But we just have a different road to travel in our sports systems if we recognized it as such. If we required coaches and parents to be informed on what is normal, they would view it as such and treat it as such.

[00:15:47] Lauren Fleshman: There's no problem in how female bodies are going through sports. It really isn't. It's how it's being met by the people around them. That's the problem.

[00:15:55] Anna Stoecklein: And that's the kicker to all of it, is that it's women and girls end up getting [00:16:00] blamed for not thriving in this system. Not just not helped, but blamed.

[00:16:06] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah. I talked to a sports psychologist recently who interviewed me and he was saying he's had girls come in, their parents brought them in, or their coaches brought them in while they're going through puberty. And the idea is that they were mentally struggling, the reason they weren't improving was that it was something between their ears, that they were holding themselves back somehow.

[00:16:27] Lauren Fleshman: And that's, I mean, that is indicative of the larger culture of what we think. If you don't understand physiology and you don't understand that this is a normal experience, you go barking up all the wrong trees, looking for what's "wrong", when nothing is actually wrong. And then the people who are brought in to help you are actually causing further harm. And they're well-intentioned, wonderful people, passionate people.

[00:16:48] Lauren Fleshman: So it's just a hole in our understanding collectively. And the goal of this book really is about consciousness raising for our community of athletes and people that care about [00:17:00] athletes so that we don't have this hole in the knowledge anymore. And I'm not a PhD, I'm a human biology major and education master's degree person, and I'm passionate about science.

[00:17:10] Lauren Fleshman: So really, I'm not the one doing the research, but I'm assembling the research that exists and telling it in a story that has a pulse so that people can absorb that information and feel it in their heart instead of spinning it around in their mind and then feel driven to change something.

[00:17:26] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. That's incredible. I mean, you've been doing advocacy work such as this almost your whole career. As soon as you started really noticing that something was off. I wanna talk about that in a little bit, cause I've got some other topics of things that you have advocated for that I wanna get to but just to clarify one more, is it safe to assume that this kind of performance wave is indicative of almost all female experiences, no matter what kind of sports that you play?

[00:17:53] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah. It extends well beyond running. One statistic that I read that really surprised [00:18:00] me was for NCAA collegiate athletes, overall female athletes, so all sports, over half of the female athletes felt that their body was wrong, that they needed to change their body in a significant way. And these are the most highly trained athletes like whose bodies are in peak form of their entire age group.

[00:18:22] Lauren Fleshman: They're the ones competing in college, and half of them think they're something wrong with their body. 90% of those people think that they need to lose weight. That the problem is that they're too big. And they believe they need to lose an average of 13 and a half pounds, which is a significant, I mean, that's like a leg. I mean, that's like a lot of weight.

[00:18:40] Lauren Fleshman: And if you have that many women aged 18 to 22 feeling that way about their body, how can that many women's bodies be wrong? They aren't, that's how. There's nothing wrong with them, but they are comparing themselves or being asked to compare themselves to an unrealistic standard, multiple unrealistic standards.

[00:18:58] Lauren Fleshman: It could be a male [00:19:00] standard of what excellence looks like, which is leaner on average, because that's what their bodies do. So they could be comparing or being compared to what a male excellence looks like at their age, or they could be getting compared to what female excellence looks like between 28 and 35.

[00:19:14] Lauren Fleshman: Like looking at Olympians in their event and saying, your body should look like that because that's what the best in the world do. But the hormonal situation of a 28 to 35 year old woman is totally different than an 18 to 22 year old woman. And those younger adolescent women, their bodies are investing heavily in peak fertility at that time.

[00:19:34] Lauren Fleshman: You are going to be softer at that time. You should be softer than your 28 to 35 year old self if all else is equal in those years and your training and your body will just naturally change over time.

[00:19:45] Lauren Fleshman: So we do have these expectations that are causing countless women to get up in the morning, look in the mirror and be like, there's something wrong with me, I need to change. And because I haven't been able to change, I'm not committed. I'm obviously not dedicated. I really clearly just [00:20:00] don't have what it takes. And that's psychological harm can last a lifetime. And the research shows that it does for so many people. They remain at war with their bodies well into adulthood and have complicated relationships with food, with self.

[00:20:16] Lauren Fleshman: And the toll on society is significant. Women having to walk around with a static, constantly running in their minds that they're not good enough. That fundamentally what their body looks like is important to their worth and that they spend significant time and energy and resources thinking about that, which limits the amount of power that we can have in the world as a group, and impacts the power that we can have as a whole group for all genders. Like we all lose when a large amount of society is preoccupied with a problem that isn't a problem.

[00:20:50] Anna Stoecklein: Amen. Absolutely.

[00:20:54] Lauren Fleshman: And sports should be the place, like we said in the beginning of this conversation, that's pumping out the most [00:21:00] confident, most embodied people. Right? In theory, cuz that's what sports supposed to be offering us.

[00:21:05] Lauren Fleshman: And if sports is doing the opposite for so many, you know, body image of athletes is worse than the non-athlete peers. I'm like, what are we even doing here? And when the solution is actually quite simple, its just, most people don't understand the female body, so learn about. And that would change a lot. That's why I will beat the drum on this until every last person I can imagine understands those basics.

[00:21:29] Anna Stoecklein: Good, good. Keep beating it and we need more. You just painted a great visual for us of those pressures, but for people who haven't played sports or have not found themselves in these situations, how would you describe where those pressures come from? Can you kind of walk us through what a journey might look like for a girl entering into puberty and beyond, and you've described what's happening to her body, but is it coaches, is it just comparing yourself to [00:22:00] other athletes? Can you just paint that picture for us?

[00:22:02] Lauren Fleshman: Well, there's the overall cultural pressure on women to be smaller. So athletes also have that. And then within the athletic world, we have another tighter standard, which is what high performance looks like. What an excellent body in sport looks like. And that is based on a male standard of leanness. And we've sort of just tossed women into the space and be like, okay, well men have been doing this, so do it like they do it.

[00:22:26] Lauren Fleshman: It's considered a compliment when a coach says, I coach my women, just like the men. It's like, well, what should you be? Yes, we're more alike than different overall, but there's some pretty important differences that need to be seen, acknowledged, and built around.

[00:22:40] Lauren Fleshman: So that's part of it. And then there's the unfortunate reality that if you lose weight in the short term, especially if you have like a significant change in your weight, you can see a short term per performance improvement. That's part of the cycle in running, but also in some other sports where you change your strength to weight ratio quickly, so you [00:23:00] hold onto the muscle power of your larger body when it weighed more, but now you have 10 pounds less and so you carry less weight, the physics are different, and for a short period of time, you're faster.

[00:23:11] Lauren Fleshman: And then the problem catches up to you because you've been restricting your menstrual cycles affected, your bone density is being depleted. All these things under the surface are happening that take longer to show up. And so in that period of time when you are running faster, and your coach is praising you, and your teammates are hearing the coach praise you for getting "fitter" when they really mean skinnier, and the message is clear to them that this is what I should be doing, and then they change their behaviors, and then it's a cycle.

[00:23:40] Lauren Fleshman: And people start, you know, social contagion, copying the behaviors of the teammates who are having success at that time. There's no way for us to see under the surface of each other's skin what's happening and what's breaking down. But it always catches up to you. 100% of the time you will experience injury, compromised immune system, compromised [00:24:00] mental health. It just takes a little bit of time.

[00:24:02] Lauren Fleshman: So that cycle has been happening. And then there's rewards in the system. So in sports, you have, for example, college scholarships in the US they could be worth $200,000 for four or five years of school.

[00:24:14] Lauren Fleshman: That kind of money and who gets the scholarships is dependent on who's the best at age 17 and 18. Now that maybe makes sense for a male body. How good you are at 17 or 18 is a pretty good indicator, a decent indicator of what you're gonna do at 20, 21 and 22. For a female body that's making a determination right in the middle of that 13 year old boy's vocal chords.

[00:24:34] Lauren Fleshman: It really doesn't make sense that that's when we determine scholarships for girls. That's a tumultuous time in our bodies, and that adds a huge amount of pressure for the range of athlete that has the maybe potential to get a scholarship. Fight puberty to try to reverse time. And even if they don't make those decisions, so many women I've spoken to will say that, yeah, I was scared of puberty. Like I did not look at puberty as [00:25:00] anything to look forward to. I looked at it as a threat to take away what I loved. Because that's how we're taught to think about it by coaches and parents that don't understand that puberty and body changes are our pathway to our eventual best self that we just require some patience for.

[00:25:15] Lauren Fleshman: So yeah, there's these economic forces, there's social forces, and then just performance forces. It's a lot. That's why parents need to read this book too. I mean, parents and coaches, but especially parents like I've got two young kids, and you gotta know what your kids are gonna be up against, what pressures they're gonna be facing so that you can be like a steady force helping them stay with themselves, with their bodies on that long-term path toward health.

[00:25:38] Anna Stoecklein: And you talked a little bit, you mentioned in there we don't know what's going on underneath the surface when you're not getting the proper nutrition, when there's disordered eating that gets into it. I'm wondering if you can kind of elaborate on that specifically, cuz that was definitely found throughout the book stories of people who are facing these outside pressures and then have some kind of disordered eating that [00:26:00] leads to injury. So yeah, it's called the Female Athlete Triad even there's a whole name around it.

[00:26:05] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, there's increased research in several areas of what ends up happening to female athletes. We are doing less studying of the environment that causes these things in the first place, the psychological environment and social environment. The stuff that you and I have been talking about so far.

[00:26:21] Lauren Fleshman: But what they are studying okay, well, what happens when an athlete has already stopped eating properly, they've stopped menstruating and they're getting broken bones. Well, that's the female athlete triad- eating disorder, osteoporosis, amenorrhea- lack of period. But by then, by the time you get to the triad, there's a lot of steps have happened that could have been intervened along the way. That could have been red flags. The reason why eating is the primary place we need to look is because it becomes a method of control for the female body.

[00:26:51] Lauren Fleshman: If you feel like your body is too big, you feel like your body's growing out of control, the only thing you can really do is change how much you're exercising and change how much you're [00:27:00] eating and what you're eating. And it may start out, and probably generally always does, as a simple thing someone's trying to do, like sleep more or do their meditation.

[00:27:11] Lauren Fleshman: It's viewed as an area where you can be more professional and make better choices and whatever. But the psychology of food restriction is very dangerous waters. Continuing to eat enough is essential for our survival. So when you start messing with that system, trying to control it, stopping listening to that voice that tells you when you're hungry or you're full, and instead saying, no, my calorie counter is what decides if I'm hungry or full, my food log is what decides if I'm allowed to eat or not. We have a wisdom inside us that knows how to eat enough. We turn that off aiming for control, and then that can cause the deadliest psychological disorder for women.

[00:27:52] Lauren Fleshman: I mean, eating disorders are the deadliest. Opioid addiction is right up there, so it's very serious and people don't realize it. They think that there's this [00:28:00] harmless thing of eating "healthier" and really. Putting themselves at grave risk of a very difficult to recover from psychological disorder.

[00:28:10] Lauren Fleshman: And then in a subclinical standpoint, REDS, relative energy deficiency in sport, that's pretty new like maybe in the last nine years, and is just now receiving a larger wave of funding that's kind of like female athlete triad light.

[00:28:24] Lauren Fleshman: So once you start having menstrual dysfunction, something like 80% of female athletes had at least one symptom of REDS. So if you're just like slightly low energy availability, you're not eating quite enough compared to what you're burning and you're doing that consistently, there's a host of things that can be affected in your body, even if you don't develop an eating disorder.

[00:28:44] Lauren Fleshman: So it's menstrual dysfunction, your immune system becomes compromised, your libido becomes compromised, your overall mental health. So increased anxiety, increased risk of depression, and also your pain tolerance is decreased, your recovery rates are decreased. So these are more of the things happening under the surface that you can't [00:29:00] see, and you don't even have to be losing weight for that to happen. You may not even notice that your just low grade deprivation over time is impacting you in those ways. So there's a lot of that happening. A huge number of female athletes are experiencing REDS in some degree.

[00:29:16] Anna Stoecklein: We've talked about the pressure, the pressure that's coming from a variety of means, a lot of it has to do with performance. But then on top of that, especially when you get into collegiate level, professional level, there is the pressure to keep weight off in the right places in order to be an attractive feminine woman. I'm wondering if we can pivot slightly and have you talk to us about the sexualization of female athletes and you know, this is obviously something I've seen.

[00:29:47] Lauren Fleshman: Oh yeah.

[00:29:48] Anna Stoecklein: But didn't give much thought to until, yeah, reading your book and what you experienced as an athlete and, oh my god, yes please tell us about this.

[00:29:56] Lauren Fleshman: Who gets to play as a professional? Like I said, it's not subject to Title [00:30:00] ix, so there's no requirement that we get as many opportunities as our male peers do. It's run by a capitalist system. Pro-athletes are marketing assets and you're invested in if the company believes that you will help them sell more shoes or more clothes or whatever the thing is, they're trying to get a return on their investment.

[00:30:19] Lauren Fleshman: And there are cultural beliefs around what makes a woman a good marketing investment that are different than what makes a man a good marketing investment. And ours are much more heavily weighted towards appearance. A female athlete is still looked at as someone who is supposed to be appealing to the male spectator, the male gaze. Which is honestly just so dumb. But that is still how we're looking at it because then the people who get to play professionally aren't even necessarily gonna be the best. They're gonna be the best people who also look the part that they want them to look like.

[00:30:52] Lauren Fleshman: There are some sports where that effect is mitigated, like sports that have league minimums, women's soccer or [00:31:00] women's basketball where they fill rosters, like there's some amount of merit involved where you're drafted based on more than your looks, and you're gonna get paid a certain minimum amount that the union has fought for and guaranteed. In track and field that does not exist. There's no league minimum and a lot of Olympic sports is the same way. So you gotta be fast and attractive to get the biggest contracts.

[00:31:24] Lauren Fleshman: And you're supposed to be kind of nice. You're not supposed to rock the boat. We've seen examples of this in our culture of like someone like Serena Williams who had displayed aggression on the court and lost her temper sometimes. I mean, male athletes are allowed to do that all the time. And her very character was assassinated when she showed any sign of that similar aggression or temper lost to a far higher degree than any male athlete was held to.

[00:31:51] Lauren Fleshman: And her body was criticized her entire career for being a fuller figured person in tennis. Her body didn't fit [00:32:00] whatever white female appearance, thinner, whatever, that tennis had decided was the most marketable thing, and just overlooking the fact that the body Serena Williams was in was kicking everybody's butt. So that's what excellence looks like. Like, it's like, but people would still say things like, oh, imagine if she lost some weight. She'd be better. I mean these, there's these assumptions that are so ridiculous.

[00:32:21] Lauren Fleshman: So yeah, there's a lot of pressure. And then there's also uniforms, like we're put into skimpier uniforms that are designed to show our body, showcase our body, showcase more skin. And what that does in track and field, you know, we've got these tiny little bathing suit bottoms and crop tops, and it really makes it so you're already feeling a pressure to be a certain weight, and then it makes you feel like if you ever venture above that, everyone's going to see, it'll be on clear display. Versus a male athlete that has a looser fitting jersey in some split leg, regular shorts, you're not gonna notice every single little change.

[00:32:56] Lauren Fleshman: But yeah, in a female athlete uniform, just being PMS-y, [00:33:00] you're gonna see everything on display and that adds another layer of stress to the athlete who then has to like manage that psychologically.

[00:33:09] Anna Stoecklein: And I just wanna point out to listeners, cuz you said this in your book of like, this isn't just marketing people subtly sending these message, this is overt. There was one marketing executive that told you you were a more valuable marketing asset as a single woman and that "men are the ones that watch sports, not women. The female athletes worth watching are the ones that appeal to men."

[00:33:31] Anna Stoecklein: And then another one said that the best seats to watch women's track begin at the starting line because "the best bodies in the sport are all lined up in little more than bathing suits."

[00:33:46] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, that was shocking to me and disgusting. These are the people that I was trying to negotiate a contract with.

[00:33:52] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah.

[00:33:52] Lauren Fleshman: So they're telling me very clearly what they value and what's important, and I am having to try to walk that line of like, well, these are the [00:34:00] people with power and money. I need them to like me and to invest in me.

[00:34:04] Lauren Fleshman: So I didn't even feel like I could say much in response to that. There were no female people I was negotiating with for money. And it's still the case that it's vast majority white straight men in charge of where the funding goes in sport.

[00:34:20] Anna Stoecklein: And then one other example was the Nike ad campaign for their new shoes, which regular listeners of the podcast will know, so women's shoes are usually just men's shoes colored pink, designed for men's feet, shrink 'em and pink 'em, or whatever they say.

[00:34:40] Lauren Fleshman: Mm-hmm.

[00:34:40] Anna Stoecklein: So Nike had come up with women's specific running shoes. Way to go. That's great news. Right? And then they asked you to be the face of it. They sent you the spec and the idea for it, and they wanted you to be out there, maybe wearing the shoes, maybe not, but completely naked, advertising these shoes completely naked. [00:35:00]

[00:35:00] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah. That was the look and feel of the ad was a naked athlete.

[00:35:03] Anna Stoecklein: Imagine it the other way.

[00:35:05] Lauren Fleshman: Oh yeah. No, no. Yeah. It's not a thing.

[00:35:08] Anna Stoecklein: For a man to be naked with a man's shoe selling to men, that would never happen. Like you are supposed to be selling for women.

[00:35:14] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, and I had to remind. I was like, we're selling these shoes to women. If it wasn't for a women's specific shoe, maybe they would've had more ground to stand on, even though I still would've objected to it, of like, okay, we're just doing brand promotion here and we want all people, quote "all people", meaning men, to like Nike even more.

[00:35:36] Lauren Fleshman: And so we take these attractive female athletes and we put them on display, but this was for a women's specific shoe. Those are the people buying the shoe. And yet the like concept hadn't budged. There are very few women in the room, so that's how these things happen. You gotta have representation in the room where the decisions are made.

[00:35:55] Anna Stoecklein: But you did get them to change the campaign?

[00:35:58] Lauren Fleshman: I did get them to [00:36:00] change the campaign, yeah. It turned out I was the woman in the room and I was willing to risk them just saying, no, nevermind we'll use somebody else. It took a lot of courage and it took a lot of mental strife to get to the point where I was willing to write the email and say, hey, I don't wanna do it that way. Here's why. Here's what's wrong with that, and here's what we should do instead. But I'm glad that I did.

[00:36:21] Lauren Fleshman: And it turned out it didn't risk the opportunity of me being in the ad. It just resulted in a better ad where I was wearing clothes and shoes and I was not bent over in a vulnerable position. That was the other thing with the look and feel is the athlete was literally bent over, but instead standing strong in myself, looking head on into the camera, not smiling, which is like the opposite of what female athletes or women in general are told to do.

[00:36:44] Lauren Fleshman: You know, smile more. I look back, and that was a long time ago. It was 2007. Now that advertisement definitely moved a lot of people and it has had some staying power as a result. And then I continue to watch athletes win things and then be put [00:37:00] in Playboy or the E S P N body issue or put in a gown or something uber feminizing or even lingerie. I think Serena Williams did some cover in Lingerie for Sports Illustrated.

[00:37:11] Lauren Fleshman: Maybe that's their choice. Maybe it was not. For me, feminism is about people just having agency and making their own choices, and if that's being naked on something, go for it. But like we do need to examine where that desire is coming from. What are the forces at play that are making that sound like a good decision to you?

[00:37:28] Anna Stoecklein: Totally. Well, I was really impressed with how you stood up to them because it was not the right choice for you and what you saw as the right choice for women everywhere who would be potentially buying these shoes. So I'm sure that took so much courage because like you said, it was not just something that you didn't wanna do, but this is your career on the line.

[00:37:48] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah.

[00:37:48] Anna Stoecklein: And when you have Nike wanting to put your face on one of their campaigns, you know where the power lies in that situation.

[00:37:55] Lauren Fleshman: Totally. It was a dream come true that then was like, oh, this is what that dream [00:38:00] looks like.

[00:38:02] Anna Stoecklein: You mentioned this with Serena a bit, but I wanna ask a specific question about how much worse this problem is for women of color and other marginalized groups? And I'll start with reading a quote from your book that sets the scene for it that will surprise no one, you wrote, "If you were fast, cute, and white, or light-skinned, you got paid. If you're just fast, maybe you got paid, but you'd better be really fast."

[00:38:26] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, I mean that's just something that has been consistent across the industry is that it's similar to how we view men as the audience for women's sports, and we've been building the presentation of women's sports around those eyes, so smaller uniforms, more skin showing, just the way we even talk about female athletes in general. We use their first names more. We talk about their bodies more. We ask about their love lives more.

[00:38:49] Lauren Fleshman: So there's that stuff, but then it's not just women, it's white women is really who is for the most part viewed as the most [00:39:00] desirable. The men who are in charge of the money are mostly white men. White straight men. It is impacting their decision making and their funding, and there are a lot of black athletes that I have known in track and field have told me that their contracts are, on average, a lot more heavily weighted towards global rankings, that they're expected to stay on top of the world to keep their money because that's what is valued is their performance above all.

[00:39:27] Lauren Fleshman: Versus white distance runners who, because they share more in common with the people giving them money out, on average, being white, being distance runners, or being sexually attractive to those white men, then you have some sort of base level of value just for existing, just for being appealing to them. And then beyond that, you get extra bonuses for being really fast.

[00:39:50] Lauren Fleshman: Not everybody gets that security, that financial baseline of money based on, hey, you're just worthwhile for existing in this sport and being [00:40:00] yourself. And that's where the racism and sexism and everything overlap.

[00:40:04] Anna Stoecklein: Like everything else, like all the other systems designed for men and designed for white men specifically.

[00:40:09] Lauren Fleshman: Exactly. Yeah. Yep. We have a lot of work to do.

[00:40:12] Anna Stoecklein: All right. Kind of a two-part question about representation in women's leadership and just gonna throw some stats out there that again will probably surprise no one. So there's the representation of women's sports on tv, right? So today women make up 40% of the athletes in the US but receive only 4% sports coverage, which as you point out in your book, this was about the same as it was 30 years ago, so has not budged.

[00:40:41] Anna Stoecklein: And then there's also the representation of women in leadership positions, both for the athlete themselves and people watching. So only 3% of NCAA men's coaching jobs are held by women, even though of course men hold 58% of [00:41:00] NCAA women's coaching jobs. I would love to hear your take on this, you know, the importance of the representation in both of these areas and kind of what you think it's gonna take to change it as well. We'll start to move into what we actually do about all these problems next.

[00:41:16] Lauren Fleshman: Well, I think that we are at a really exciting time. I think that people are more ready than ever for women's sports, and I'm hoping that the timeliness of this book, I hope that 10 years from now people go, oh wow, this book is so dated. Women's sports are on TV all the time now, and they're getting paid tons and they aren't required to be in little bikinis when they're racing and whatever.

[00:41:39] Lauren Fleshman: And that very well could be the case, and that would be the best thing in the world that could happen to me is to have my book become irrelevant as quickly as possible. But I think that coaching stat that you gave is really telling. The fact that I don't even hear women talking about a goal of getting half the coaching jobs of men's sports. It's so pie in the sky. It's like sending someone to [00:42:00] walk on Pluto or something. I mean, it's just like, you wouldn't even think of it.

[00:42:02] Lauren Fleshman: It's already been so hard. We've been stuck at 42% of the women's sports coaching jobs for a very long time.

[00:42:10] Anna Stoecklein: Of the women's sports.

[00:42:12] Lauren Fleshman: Yeah, of women's sports. Like we can't even get half of those jobs. We can't even get half of those jobs. And before Title IX, we had 90% of the jobs in women's sports. And yes, they were club and intermural for the most part, but still we did have those jobs and we had collective wisdom of women working with women, working with female body. And that was all lost. That was one of the bummers about Title ix that, predictably, once the jobs became higher paying and higher status as they were part of the NCAA and everything, then men came in and got those jobs.

[00:42:45] Lauren Fleshman: And the way that coaching works, it's a lot about who you know and women are being hired in record numbers in the assistant role where they are responsible for the emotional labor and talking about things like periods, like talking about subjects that male [00:43:00] coaches find uncomfortable, even though they're just essential functions of half the population, like periods and breast development and whatever.

[00:43:07] Lauren Fleshman: They should be as easy to talk about as an elbow or an Achilles tendon, but we aren't there yet, and so we hire women to do it and they're paid less. The head coaching staff is motivated to keep them in that role versus promote them. They're serving a valuable function that they find uncomfortable to do themselves.

[00:43:24] Lauren Fleshman: So there's definitely a lot of factors at play here that are keeping the numbers and coaching from changing much. Also, if you don't have enough female head coaches in women's sports, you're not developing a pipeline that could even apply for men's sports jobs. It's really a struggle.

[00:43:38] Lauren Fleshman: But when it comes to, just kind of going back really quick about optimism, women's soccer in the UK was watched an incredible amount of time, and when we have these moments with women's soccer in the us, same thing has been going on a little bit longer than in the uk, that phenomenon.

[00:43:52] Lauren Fleshman: But we do know that I think people are ready. I really do. I think that we have some like archaic things happening [00:44:00] in sports marketing that aren't really indicative of what the average person wants out of sports. And as soon as they figure that out, they can start making some changes.

[00:44:08] Lauren Fleshman: But when you have a gay athlete with a short haircut, Megan Rapino, being one of the most beloved female athletes in the world, you're like, okay, this obviously isn't about a straight white man, what they find appealing, right. She is highly paid, highly celebrated. She's for us. She is for the women's sports crowd, and if men wanna watch it too, fantastic. You are welcome to. We're not gonna center your desire for the product, but you are more than welcome to come enjoy the games.

[00:44:38] Anna Stoecklein: I am very happy to hear your optimism. So you feel optimistic overall?

[00:44:42] Lauren Fleshman: I do. And I feel like athletes like Simone Biles, Naomi Osaka, primarily women of color, Alison Felix, Alicia Montono, these women who have come out and been like, no, I'm not trying to be like the top men athletes. I'm not trying to appeal to you. This is who I am. This is what I need. This is what I'm [00:45:00] doing. Get used to.

[00:45:01] Lauren Fleshman: And Serena was such a great example of that. Simone Biles deciding not to do one of the events at the Olympics to protect her mental health. Naomi Osaka deciding to break the rules and not do press conference for her mental health. I mean, they're just saying, no, this is how it's gonna be. I don't care what your rule is, or whatever your norm is. I have my own needs here and we're gonna change the norms around those. And we really need to develop more of that swagger as female athletes and women in general in our offices.

[00:45:26] Lauren Fleshman: And it's understandable that we haven't had that in large numbers for many decades because it's been hard enough just to get in the room and survive in the room. And it's natural survival strategy to mimic the dominant behaviors in order to succeed in the environment. That is what you have to do at first, but then once you get enough critical numbers in there, you don't have to do that anymore.

[00:45:47] Lauren Fleshman: There's enough of us here to like change the actual culture of this place instead of just enduring shoulder massages at work. Right? Like we can change what is expected.

[00:45:58] Lauren Fleshman: The Me Too movement makes me [00:46:00] feel optimistic. There have been a lot of cultural changes of expectation of what normal is since then, and the same thing I think is on the cusp of happening in sports, women's sports specifically.

[00:46:10] Anna Stoecklein: Great, great. So yeah, in terms of what it's gonna take to change it. I mean, you've given us a good picture there. It's a lot of talking, telling stories, women embracing their swagger, all of it. Is there anything else that you would say, just in terms of concrete actions or what it's gonna take to get to this equal playing field?

[00:46:32] Lauren Fleshman: I think that we need to expect more from men in women's sports. Like we need to expect them to have, I think, a mandatory coaching certification for working with female bodied people. There's enough physiological differences, biological differences that deeply impact our experience in sport and the amount of harm caused by participating in sport in environments where people are ignorant to that, like there's so much harm being caused that there should be a mandatory coaching certification to work with female athletes [00:47:00] where you have proven you understand their biology and physiology. And you can say the word period without euphemisms, you know, you can comfortably...

[00:47:08] Anna Stoecklein: The bar is so low.

[00:47:10] Lauren Fleshman: It's so low, honestly. It really is so low. So low. And then if we could do something simple like that, which I know we can do, cuz we have safe sport mandatory protocols for coaches now to be educated on sexual abuse and stuff like that. So we can do it, we can make it mandatory. That would go a long way.

[00:47:27] Lauren Fleshman: And then I think the other thing is, yeah, just women developing their collective swagger. Supporting other women in sport. Like a certain amount of the obstacles are very real obstacles that exist, and then a certain amount of our remaining obstacles are not putting up with it anymore.

[00:47:43] Anna Stoecklein: Cultivating our collective swagger, this is one of my favorite lines from this whole talk. So in addition to that, any advice that you would give to a woman or a girl that's navigating the sports world as it is today?

[00:47:56] Lauren Fleshman: I mean, definitely pick up Good For a Girl. You know, the stats and [00:48:00] data are in there that are important, but also one of the most powerful things I'm seeing is people will read the book and then they'll write to me and say, this completely changes how I view my experience. Like this fundamentally shifted things inside me.

[00:48:13] Lauren Fleshman: And that's because it's a sports story and it's told through a first person narrative where you're running in my shoes with me. So like if you're just reading a scientific article, something in a journal, it doesn't land the same way it stays up here in your head. It brings it down into your heart and into your body when you read it through story. And so I would say do that. It'll have the best impact possible.

[00:48:34] Lauren Fleshman: And then if there's anything you take away, it's just like have respect for your physiology, for female bodied norms. Your development towards your strongest self is gonna look different than your male peers, and you are right on time. You are doing what you're supposed to be doing. So spend as little energy as possible fighting against that. Let yourself become, and yeah, learn about [00:49:00] nutrition and learn about recovery, and learn about those things, but not with the goal of changing yourself.

[00:49:05] Lauren Fleshman: This is with the goal of taking care of yourself. Just by being so much easier on yourself. You will get to the other side of any changes in a healthier way, and you will have less static bouncing around between your ears stopping you from doing your unique work in the world.

[00:49:21] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. Thank you. A kind of final question that I like to ask is, if people take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:49:33] Lauren Fleshman: There's nothing wrong with you. That's it. There's nothing wrong with your body. And to dig in and like, really, if you find yourself being hard on your body, put the spotlight on who's making you feel that way. Take the spotlight off of what your stomach looks like in your jeans. And put it on who's making me feel this way?

[00:49:53] Anna Stoecklein: I love that. I love that. And obviously that can apply to all people, all women, not just athletes, [00:50:00] but all people...

[00:50:00] Lauren Fleshman: Absolutely.

[00:50:01] Anna Stoecklein: ...as well. So what a beautiful sentiment to end on. Collective swagger, and move the spotlight.

[00:50:08] Lauren Fleshman: That's it. Let's do it.

[00:50:09] Anna Stoecklein: Let's do it. Lauren Fleshman, author of Good for a Girl. Thank you so much for your time today. It was such a lovely, lovely conversation.

[00:50:19] Lauren Fleshman: Thank you. Thank you so much.

[00:50:24] Overdub: Thanks for listening. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, and think we need more of women’s stories in the world, be sure to share with a friend! And subscribe, rate and review on Apple, Spotify or wherever you listen to help us beat those pesky algorithms.

[00:50:42] Overdub: Follow us on socials for more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes.

[00:50:48] Overdub: And for access to bonus content and ad-free listening, consider becoming a Patron of the podcast. This is the best way to help me continue to put out [00:51:00] more and better episodes. You can also buy me a metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs.

[00:51:07] Overdub: And in exchange, you’ll receive my eternal gratitude and good nights sleep knowing you are helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.

[00:51:18] Overdub: This episode was produced and hosted by me, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:51:22] Overdub: It was edited by Maddy Searle. With communications support by Jo Cummings.A special thanks to Amanda Brown, Kate York, and Dan Kendall for their ongoing production support and invaluable advising.