[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Anna Stoecklein: Welcome to Season 3 of The Story of Woman. I'm your host, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:00:05] Anna Stoecklein: From the intricacies of the economy and healthcare to the nuances of workplace bias and gender roles, each episode of this season features interviews with thought leaders who provide fresh perspectives on critical global issues, all through the female gaze.

[00:00:20] Anna Stoecklein: But this podcast isn't just about women's stories. It's about rewriting our collective story to be more inclusive, equitable, and effective in driving change. It's about changing the current story of mankind to the much more complete story of humankind.

[00:00:37] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:38] Anna Stoecklein: Hello, and welcome back. Thank you so much for being here. Today we explore topic that with the rise of AI is feeling more urgent than ever: surveillance. You know, 1984 is big. brother kind of surveillance, [00:01:00] CCTV, the tracking of our personal information, activities, and even medical data through our phones, computers, and other devices, and so on.

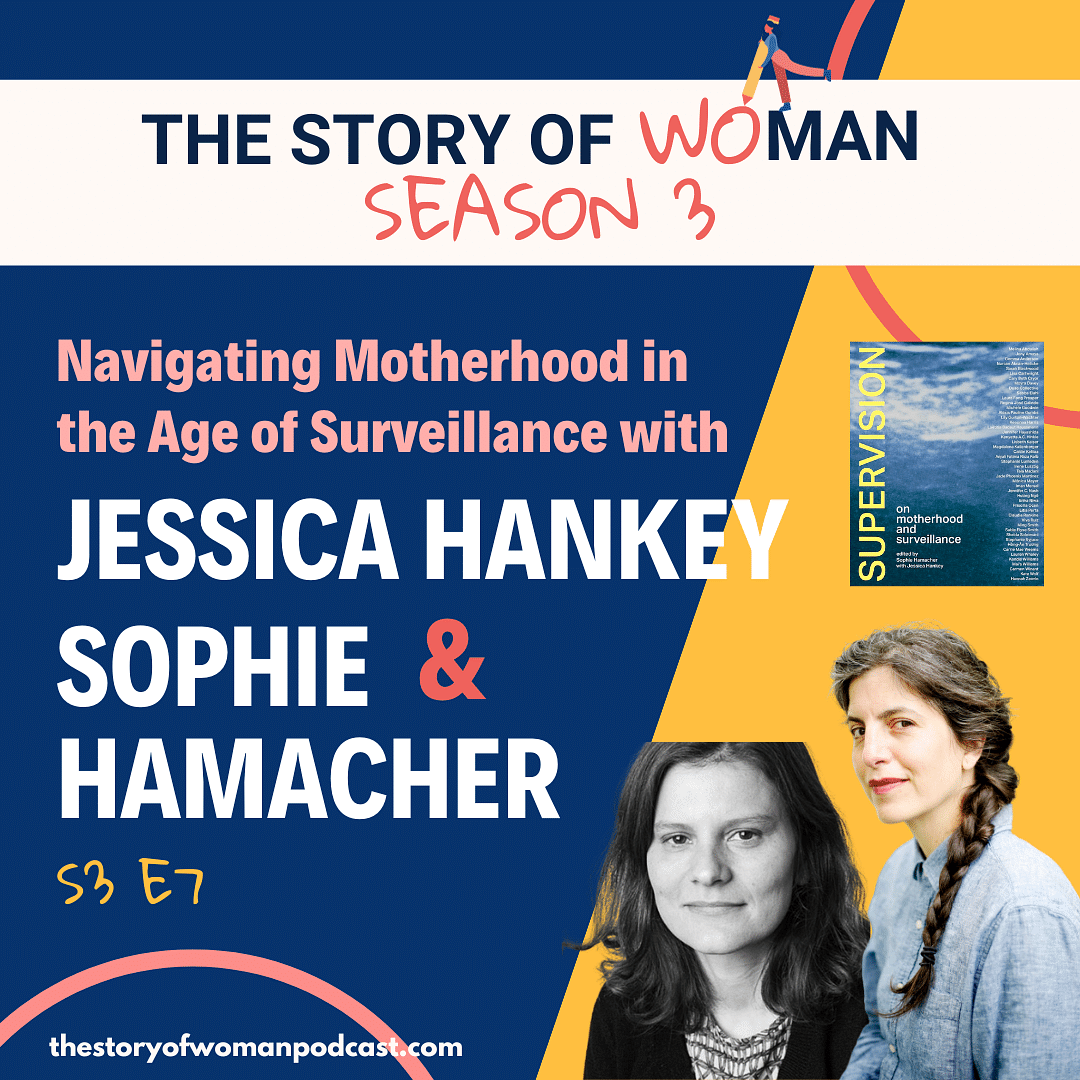

[00:01:09] Anna Stoecklein: But we're looking at it through the lens of motherhood today. The ways in which mothers behaviors and bodies are being observed, made public. Exposed, scrutinized, and policed like never before. I'm speaking with Sophie Hamacher and Jessica Hankey about their book, Supervision.

[00:01:29] Anna Stoecklein: Sophie is an artist, filmmaker, curator, and teacher. Among other things, her films are investigations into the silences and gaps of political and historical narratives. Currently, she teaches at the Maine College of Art and Design in Portland, Maine.

[00:01:45] Anna Stoecklein: Jessica is an artist and the publisher of Orbis Editions, an artist run platform for publications and performance. She's held editorial and positions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the L. A. County Museum of Art, and the [00:02:00] Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles.

[00:02:03] Anna Stoecklein: Together, they created this first of its kind anthology gathering the work of 50 contributors from diverse disciplines and composed of both visual art and writing that explores how surveillance impacts contemporary motherhood.

[00:02:17] Anna Stoecklein: In our conversation today, we talk about how we've seen surveillance in motherhood in the past and how we continue to see it today. The state's long history of sowing fears to allow for greater surveillance, as well as the role advertising has played. We talk about baby monitors and abortion and the importance of finding community and expanding our ideas of motherhood.

[00:02:38] Anna Stoecklein: I'd like to give a special thanks to Kulani Jenkins, who helped out as the assistant producer of this episode, the first one of those for The Story of Woman. I couldn't have done it without her, so thank you so much, Kulani.

[00:02:53] Anna Stoecklein: As always, if you like what you hear today or you think it's important enough that more people should hear it, please feel free [00:03:00] to share with a friend. But for now, please enjoy my conversation with Sophie Hamacher and Jessica Hanke y.

[00:03:07] Section: Episode interview

[00:03:08] Anna Stoecklein: Hi, Sophie and Jessica. Welcome, thanks so much for being here.

[00:03:13] Jessica Hankey: Thank you for having us.

[00:03:15] Sophie Hamacher: Hi.

[00:03:16] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. I'm really excited for this conversation and to start, I just love to have you tell us a bit more about your book, Supervision, a little bit about the purpose of it, how you up with the idea and a bit about the composition of it. What it's made up of, what readers can expect when they open it up?

[00:03:38] Sophie Hamacher: This is Sophie. The Idea behind this book was very personal early on. When I first became a mother, I began thinking of the act of looking and watching in a different way. I was constantly looking at my newborn baby, and I was thinking about looking because I'm an artist and a filmmaker, and [00:04:00] filmmaking has always involved a very concentrated looking for me.

[00:04:05] Sophie Hamacher: I think there was a real need to explore the topic of surveillance specifically when I felt like I couldn't really hold a camera anymore or look through it in the same way that I had before. And the reason why I couldn't look through this camera anymore was because my first child was born and I kept getting distracted. I kept looking at my child instead of looking through the viewfinder and concentrating on composition and lighting. I started thinking about the word 'surveillance' and it's definition, which is close observation. I thought about looking and watching and found it intriguing that language always contains so many nuances.

[00:04:44] Sophie Hamacher: Then I started thinking about baby monitors and watching children with baby monitors and through screens. And the baby monitors made me think of the connection between the history of photography in relation to military research. I really wanted [00:05:00] to understand this trend of watching children through monitors to ease anxiety.

[00:05:05] Sophie Hamacher: Advertising also played a big role, because that creates this anxiety in the first place. I was drawn to thinking about how this technology, so the baby monitor as the first thing that I started thinking about and researching, I was drawn to really thinking about how that technology infiltrates domestic space. And I wanted to explore the larger topic of care and control.

[00:05:29] Sophie Hamacher: The book is made up of a collection of essays, poetry, artworks, and interviews. It includes 50 contributors.

[00:05:38] Jessica Hankey: This is Jessica talking. As Sophie said, it was such a collective effort and we really wanted to put all the names of the contributors on the book, all 50 names, and that's what we did. We were able to do that. I think we started from questions about how mothers might see differently and that really came from Sophie's [00:06:00] own experience of pregnancy and mothering.

[00:06:03] Jessica Hankey: And as we worked on it more, we started to think about the ways in which mothers not only watch, but are watched, right? And they are watched a lot. So, that really expanded the book and allowed us to begin to bring in more voices and as more voices came in through contributors and interviews, another concern was raised which is how mothers prepare their children for life in a world in which they are surveilled. And so the book really became about the ways that pregnancy and raising children is impacted by watching and being watched. By ourselves, by our children, the police, medicine, welfare, at school, and then, of course, the legal efforts at control of our reproduction through constraints on abortion.[00:07:00]

[00:07:00] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. Yeah. And we'll get into some of these specifics here shortly, but I like this little sentence of summarize exactly what you both were saying. I think this was from the preface that, you know, this book brings together 50 contributors, exactly as you say, "50 contributors from diverse disciplines to ask what the relationship is between how we watch and how we are watched and how the attention that mothers pay to their children might foster a kind of counter attention to the many ways in which mothers are scrutinized."

[00:07:36] Anna Stoecklein: So more question kind of on the composition of the book. So there's loads of beautiful photos, and there's interviews, and there's essays. lot of the book is mothers in conversation with one another, not just, you know, one mother saying her part, so I'm curious why you chose that way of communicating these [00:08:00] narratives? Why did you choose to have the majority the book be mothers in conversation with one another?

[00:08:03] Sophie Hamacher: This is Sophie. So much of this project came out of being isolated and really needing community. I had moved from New York City to rural Maine. And so when the pandemic started, my life didn't really change very much. I live in a house where you can't see another house. I know many women have talked about how isolated they feel after giving birth. And that was absolutely the case.

[00:08:27] Sophie Hamacher: I say in the preface motherhood is never really one experience, but many. And I wanted to talk to other mothers, to see how they were raising their children, how they had dealt with the revolution that is becoming a mother, and what it was like for them to watch and be watched while mothering.

[00:08:45] Sophie Hamacher: I saw the interview process as having the possibility of being a kind of collaboration. So the collaboration was very much between me and Jessica, but also between all of these mothers that we included and spoke with in the process. So to [00:09:00] name a few examples, I spoke with a lawyer working with mothers in prison. I spoke with other artists. I spoke with an environmental studies professor, a sociologist, a child psychologist, a children's book author, and a journalist specializing in reproductive health. It was really an asking and learning process.

[00:09:21] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah there was definitely a through line of community and connection and camaraderie, and I have a line written down here that talked about the invisible string that connects our community of mothering people and that really came across in the book.

[00:09:39] Anna Stoecklein: And as you said, from your own personal experience, Sophie, and I've heard, you know, I'm not a mother myself, but I've heard from plenty others and from the books I read and the people that I've talked to, isolation can very much be a feeling during these stages. So it really was a line through the book of this community and connection.

[00:09:57] Anna Stoecklein: And I thought that was such a beautiful, a beautiful [00:10:00] piece and I'm also curious, before we get into the more specifics of the book, had any difficulty getting this out into the world because, uh, there was someone in your book, Irene Lutzig, who talked about difficulties she had getting one of her films programmed, um, a film called The Motherhood Archives, because she kept hearing people tell her that this centered around women's issues, which were niche, or, you know, maybe their wife might find it interesting, and again, far from the first time I've heard or read something like that. I'm curious if you all came up against that at all, uh, or any friction?

[00:10:35] Jessica Hankey: This is Jessica talking. I should say that, Anna, I'm also not a mother. But we know that the vision and experiences of mothers are very important and are underrepresented in our culture, in our discourse, right? So you and I can recognize that we need to reflect more on the vision and experiences of mothers.

[00:10:58] Jessica Hankey: But, no, in [00:11:00] fact, we didn't encounter a lot of friction because we made this book with very little money through my small, tiny art press. And it wasn't until the book was about 98 percent complete that MIT signed on to co publish with us. So we had a lot of freedom, but not a lot of support in making the book.

[00:11:20] Jessica Hankey: And, you know, surveillance is not really a familiar frame for thinking about motherhood, so we do have to explain the concept of the book to people, but we found that when we reached out to many of these incredible contributors to the book, that they really understood what we were aiming for, and they signed on, even though it was just us.

[00:11:45] Jessica Hankey: So people like Jennifer Nash, who's a scholar at Duke University, and she's written a number of books, but she wrote a book called Birthing Black Mothers that came out in 2021. She signed on pretty early. So did Lisa [00:12:00] Cartwright, who is one of the founders of the field of Visual Culture Studies. And another person who signed on early, is the amazing poet, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who is also an activist, and she's a co editor of the anthology, Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines, which I think came out in 2016.

[00:12:23] Jessica Hankey: And this, you know, their joining us in making the book really helped us to become more ambitious about what the book could be, what it could hold and take on. And then, really it was a little bit later that some of this work concerned with the impact of technology came into the book.

[00:12:41] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, so exactly as you say, surveillance is not a familiar topic necessarily in motherhood, even though surveillance in general is a topic that people are becoming [00:13:00] increasingly aware of. But there could be listeners, you know, who at this stage are even a little confused as to what surveillance and motherhood, you know what, maybe they're familiar with mothers being scrutinized, but surveillance is kind of a newer way of thinking about it and looking at this.

[00:13:16] Anna Stoecklein: So I want to help clear up any of that and get into some of the specifics examples. So reading first, quickly, Sophie, something that you wrote. You wrote,

[00:13:26] Anna Stoecklein: "As I became absorbed with tracking and monitoring my child, I was increasingly aware that I was a subject of tracking and monitoring by others. Advertisers, medical professionals, government entities, people on the street. I began to wonder about the relationship between the way I watched her and the ways we were being watched. And that in this age of surveillance, mother's behaviors and bodies are observed, made public, exposed, scrutinized, and policed like never before."

[00:13:57] Anna Stoecklein: So, we are in an [00:14:00] age of surveillance, right? And this kind of surveillance and being watched and CCTV, digital devices, all these other technologies is increasing across the board. So help us understand how does this happen within motherhood, specifically, and can you give some examples of where we see this in motherhood?

[00:14:16] Sophie Hamacher: Yeah. So, I think the most obvious example are really the baby monitors, which was the first technology that I went to in my research. And it was, I wouldn't even call it research. I ordered a bunch of different baby monitors and began experimenting with them as an artist.

[00:14:33] Sophie Hamacher: So I was really interested in the images that they produced. And I wanted to record everything but the baby. So I was interested to see like, can I start experimenting with this technology, not by clamping it onto the crib, but by I don't know, taking a landscape shot, for example.

[00:14:51] Sophie Hamacher: How does the zoom work on this thing? And why can you record with it in the first place? So, I was really fascinated by the [00:15:00] pressure put on me, or put on mothers in general to monitor children, to keep them safe. And yeah, the baby monitor was really like the beginning of the interest.

[00:15:11] Sophie Hamacher: But our book is not really about technological surveillance. Although technology is included in the preface and I explained this experimentation with the baby monitors. And there's also another contribution in the book that's very much about technology.

[00:15:26] Sophie Hamacher: But I think we're thinking of surveillance in a much broader scope. And I think some of the questions that the book raises are, for example, the challenge to actually see mothers, the overdetermination of motherhood with symbolic meanings and controlling images. The differentiation between mothering and the state granted status of motherhood. The right to be seen as well as unseen. And especially also the power of collectivity. Jessica, do you want to [00:16:00] add something?

[00:16:00] Jessica Hankey: Uh, yeah, thanks. I also think we can of course talk about abortion in the United States, right? And Sophie and I, and I mean, we're not alone, we see issues about abortion as being central to a discussion about motherhood. So surveillance and being watched have increased so much in the years prior to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and also since it was overturned in 2022.

[00:16:27] Jessica Hankey: In states that have banned abortion, it's dangerous for people to use period tracking apps, for example, because law enforcement could actually use that as evidence of a terminated pregnancy. People seeking out of state abortions are being urged to leave their phones at home, which can be very difficult if you're traveling many hours.

[00:16:49] Jessica Hankey: They're being told to pay cash for health care and to just avoid digital tracking of any kind because that also could be [00:17:00] subpoenaed by law enforcement. It's really an unfolding story, and we don't know how the boundaries will be drawn, and so that's why they're urging people to just steer clear of all of this data tracking if they can.

[00:17:14] Jessica Hankey: And another thing I would just raise, partly because it's so unbelievable and so dystopian, is the Texas bounty hunter abortion ban. I don't know if that made news in England, it engages regular citizens to spy and report on each other, and they can even make a profit of up to 10, 000 by doing that.

[00:17:35] Jessica Hankey: Michelle Goodwin, who's a bioethicist and a legal scholar, she wrote a book that came out, In 2020 called Policing the Womb, which anticipates a lot of these developments and a lot more. And she's a contributor to the book.

[00:17:51] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, I mean, all of that is, is just. I mean, there are so many words, [00:18:00] uh, wild, it did make it over here in the news for sure, the Texas bounty hunting, and this is definitely, those are great examples of the way mothers or women in general are being surveilled with not being able to use these very helpful and important apps because other actors might use that data to put them or people they love in prison.

[00:18:26] Anna Stoecklein: And you you had stuff throughout the book and there was something in the preface, a section called Monitoring and Marketing the Maternal and in that you had a quote about the state's "history of sowing fears about public safety as it pushes for greater surveillance powers and that as parents it can sometimes be impossible to distinguish legitimate fears from manufactured ones. This has never seemed more true today."

[00:18:53] Anna Stoecklein: So I'm curious to hear you talk to us more about that, because [00:19:00] this with reproductive rights being rolled back, you know, there is this kind of underlying fear throughout that now that you're saying that has got me thinking about, how this is not the first time that that has happened.

[00:19:15] Anna Stoecklein: Um, so what can you tell us about, I guess, the history of state's sowing fear in this way and also how marketing and consumerism feeds into all of this?

[00:19:29] Sophie Hamacher: Yeah, I think, the book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism that came out in 2019 by Shoshana Zuboff, who was a former professor at Harvard really helped me in my research. I mean, what an extensive amazing book on the kind of relationship between the commodification of personal data and surveillance.

[00:19:50] Sophie Hamacher: So, Yeah, she talks about it from a very, kind of general perspective of targeted advertising, really, but when it comes to [00:20:00] motherhood, this gets more nuanced. So targeted advertisers create doubts in mothers about their ability to care for their infants. So that's really the strategy. And that's a well known advertising strategy, since I think about the 1930s, maybe 1940s, to create these doubts that the mothers have the ability to care for their infants and then they scare the people into buying their products, your child will only be safe if you watch them with this Biometric baby monitor buy it today. So the biometric baby monitor doesn't just monitor the sounds and the video, but, actually monitors the baby's heart rate. You can put a little, wrist bracelet or ankle bracelet on the baby. And that's all part of the, you know, like even since the beginning of making this book, the technology has developed quite a bit. So yeah, there's profit in fear. And that's really what corresponds to the state's history of sowing fears [00:21:00] about public safety, which allows them to push for greater surveillance powers.

[00:21:04] Sophie Hamacher: We saw that unfolding really during the pandemic, for example, right? There was a lot of fear around the virus and through that we were able to see how states began surveying their entire populations.

[00:21:20] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. Yeah. And, on that, on that point of, you know, thinking about the different devices have now that can better track your baby's health, there could be some people that say, well, I don't see what's what's wrong with that. I would love to know more about my baby's health. I would love to be able to know quickly before things escalate, if something in some way.

[00:21:45] Anna Stoecklein: So can you talk to me, so can you talk to us about that or to what you might say to someone who has that thought, you you write in the book, there's this difference between benevolent and oppressive surveillance [00:22:00] and maybe that stems into this idea. Can you help us understand, um, where's the line, I guess, because not all surveillance is "bad".

[00:22:09] Jessica Hankey: I'd like to just chime in here, this is Jessica, just in one area building on what Sophie said, which is, you know, during the pandemic, the online classroom was a solution that was offered. And what we saw, right, is the acceleration of bringing really what is school surveillance directly into people's homes.

[00:22:35] Jessica Hankey: And one example of the consequences of that was in 2020, a nine year old named Kamari Harrison was actually suspended from school for six days because his teacher saw a BB gun in the background of his virtual learning session, like in his video. And that's just, I think, an example of kind of the Wild West, of bringing these authorities [00:23:00] into the home. It's different from what you were just asking about, about tracking your infant. But I'd just like to tag that, flag that for people.

[00:23:08] Sophie Hamacher: Yeah, I think that's a really good question. And that's actually a question, I mean, the question that you posed about benevolent versus oppressive surveillance, that question really was leading a lot of my early interviews. I asked the whole kind of first set of people that I interviewed a question about the possibility of surveillance being benevolent, because I kept asking myself in the process, don't we closely observe our children and don't they closely observe us?

[00:23:36] Sophie Hamacher: isn't that how parents and children learn? And isn't that surveillance? That question was really the very beginning of thinking about, like, what is surveillance? And is there a way to survey with care? And isn't the surveillance that I was just speaking about earlier in terms of the pandemic, isn't that a caring and somewhat benevolent [00:24:00] surveillance.

[00:24:00] Sophie Hamacher: But the more I spoke to other mothers and especially mothers of color, the more it became clear that no, there is no benevolence in surveillance, especially if the surveillance comes from the state. For example, I asked Jennifer Nash, the professor from Duke university that Jessica mentioned earlier, can surveillance be something that is desired when it is motivated by an interest in care and protection. What does surveillance as care mean to you?

[00:24:29] Sophie Hamacher: Her answer included an example of the state keeping track of breastfeeding rates by race and the result of that looking and feeling like surveillance and compulsion instead of a compassionate effort because the women were robbed of a choice in their infant feeding practices as a result. Jessica, I think you have some other examples, no?

[00:24:49] Jessica Hankey: Yeah, and I just want to add on the subject of this program of tracking mother's breastfeeding, that WIC, which is a supplemental [00:25:00] nutrition program in the U. S. that stands for Women, Infant, and Children, they were actually tying access to more nutrients and food to whether or not mothers were breastfeeding. So it was coercive in that way, even though it was under the guise of being benevolent because breastfeeding is good for babies.

[00:25:19] Jessica Hankey: I also, something I want to flag in our conversation, is this language of benevolence, sometimes also what it's doing is it's really privileging the needs of children over those of their mothers.

[00:25:31] Jessica Hankey: And we see that a lot in some of the debates about reproductive health care. Oh, what are the needs of the fetus? The mother's needs don't matter. So I just want to put that in there as a seed of something we can keep thinking about when we're being benevolent. Who are we being benevolent toward? And how are we interpreting the needs of individual potential mothers and also families?

[00:25:54] Jessica Hankey: So I think one of the great questions of the book relates to how we need a government that cares [00:26:00] about us. We need healthcare, education, access to healthy food, and the problem is that these forms of care are often used by the state to control and punish families, as we heard in the example about the WIC program.

[00:26:16] Jessica Hankey: So, two contributors to the book, Caitlin Kalia and Stephanie Lumsden, who are scholars of indigenous history and gender studies, are very clear on this point about the benevolence of the state as it surveils, families and communities. They talk about the state's history of using claims of benevolence to justify policies aimed at destroying Indigenous families and communities, including forced sterilization of Native women through the Indian Health Service.

[00:26:47] Jessica Hankey: It's been estimated that in the 1970s, as many as 25 percent of Native women of childbearing age were sterilized through these programs. Or, under the guise of [00:27:00] concern for Native children, there's the forced removal of those children from their families and communities into unsafe institutional spaces.

[00:27:09] Jessica Hankey: Or for another example, and there are many, Priscilla Osen, who's a contributor and a legal scholar, talks about how these non criminal systems, institutions like welfare, schools, and hospitals, disproportionately regulate poor women of color and can lead to incarceration. So for example, a family receiving welfare is forced to allow state agents into their homes through what are called home visits. They are forced to share personal information about themselves and their families. It's demeaning, and increasingly, it's a path to incarceration, because welfare agencies have shared data with law enforcement, making these dangerous encounters for families.

[00:27:54] Jessica Hankey: Even a doctor's visit can lead to warrantless searches and arrests, so [00:28:00] we're not going to get rid of some of these programs, we need them, but it's important to advocate for privacy, for dignity, in these programs, without surveillance.

[00:28:09] Anna Stoecklein: I think that makes a lot of sense and, you know, these examples I think will be quite obvious to most of us as oppressive surveillence. guess I'm wondering, you know, back to that example of being able to look at your baby's heart rate. How do we know when it's oppressive and when it's benevolent? You know, how do we even know it's coming from the state, did you learn anything on that front or anything you can share to help us discern when its not as clear?

[00:28:41] Sophie Hamacher: I think the main premise of this book is really to talk about and to list a lot of forms of surveillance, and just lay them on the table. And speaking of them and identifying them can be a form of power and a form of kind [00:29:00] of taking back the power, at least like seeing it, and seeing all of the problems, Jessica, what do you think?

[00:29:07] Jessica Hankey: Yeah, I think we, we've had trouble answering this, Anna, because we don't want, if mothers and parents want to monitor their infants heart rate, et cetera, through these new devices, we don't want to judge them or deny them their own, you know, rights to do that. We just want to raise questions about it because sometimes it can seem like we think that more information is always better.

[00:29:35] Jessica Hankey: And sometimes, you know, it's good to kind of hit the brakes a little and think about you know, what is this, how is this changing the dynamics in the home?

[00:29:44] Jessica Hankey: The, The increased ways of tracking your infant's health, those are options for people and we don't want to tell them that they can't use them.

[00:29:53] Anna Stoecklein: I think that makes a lot of sense. It's about [00:30:00] being aware because so much of this, you know, is kind of from the outside and we take it as we just can take it in stride without questioning. And then, um, yeah, like you say, just increasing awareness around all of this. And a part of that, you know, throughout the book, you really, I think you did something clever, which is you challenged those that you were in conversation with, and in turn the reader to consider ways in which their everyday parenting duties could be a form of surveillance.

[00:30:31] Anna Stoecklein: So again, just kind of increasing that awareness, just taking a look as a first step there are so many ways in which, um, we may have internalized some of the surveillance against ourselves and others. So can you talk more on that point, what that internalised surveillence looks like?

[00:30:44] Sophie Hamacher: When I think about internalized surveillance in terms of myself, I think about the ways that I unconsciously watch other mothers and judge their parenting and choices. And I'm worried that others are judging me. I think that's one of the very obvious [00:31:00] examples of this internalized surveillance.

[00:31:02] Sophie Hamacher: I want to latch onto something that we said earlier about the breastfeeding. I think breastfeeding generally is another area where a lot of women feel an immense amount of pressure from society, from the state, in the example of the WIC program, for example. And through the, yeah, the pressure is felt also, because of this internalized surveillance.

[00:31:24] Sophie Hamacher: We have two contributors whose work we included that make work of, about this self surveillance in relationship to breastfeeding. One is Sarah Blackwood who contributed a short essay about her meticulous, measuring and tracking of her breast milk.

[00:31:45] Sophie Hamacher: And another one is Gemma Anderson contributed this very beautiful colored pencil drawing, where she's also measuring breast milk. She has twins. So that's why if you look in the book, you can see [00:32:00] this beautiful colored pencil drawing by Gemma Anderson, who is also really dealing with internalized self surveillance in terms of the measuring of how much she's lactating.

[00:32:12] Sophie Hamacher: But I learned through my interviews that for many people surveillance is a word that they reserve for the workings of the state and not for their own parenting or internal activities or internal thinking, especially perhaps those mothers who are disproportionately targeted by the state. So black and brown mothers, migrant mothers, trans mothers, the mothers of trans children, for example, I'm thinking again of two other contributors.

[00:32:41] Sophie Hamacher: Kiana Harris, who is a writer and prison abolitionist. And Malina Abdullah, who's a professor of pan African studies and one of the founders of Black Lives Matter in LA. Both of those women talk about teaching their children to police and monitor themselves in public to [00:33:00] protect them from a state apparatus that seeks to criminalize them. So they both talk about this as a loving form of care that they regret, because it, denies their children a certain amount of freedom in order to keep them safe.

[00:33:14] Sophie Hamacher: And, Malina especially, Malina Abdullah, is very clear that she would not use the word surveillance to describe this. For her, surveillance is really always coming from the state.

[00:33:25] Jessica Hankey: This is Jessica. This question also makes me think of a piece by the artist Magdalena Kallenberger in the book. It's really a very funny and moving piece. Which is called The Terrible Two, and it reproduces text messages. I think it's somewhat fictionalized, but it reproduces text messages she sent to the father of her two year old son as she spiraled while having to parent him by herself. She's fighting with the dad, and confessing how she's in conflict with her son, and she says that the messaging becomes a [00:34:00] self monitoring device. And she, quotes Franz Kafka. I'm gonna try not to butcher the quote and share it with you.

[00:34:08] Jessica Hankey: He says, The inescapable duty to observe oneself. If someone else is observing me, naturally I have to observe myself too. If no one observes me, I have to observe myself even closer.

[00:34:22] Jessica Hankey: Ad break

[00:34:23] Anna Stoecklein: I . You've kind of already you've touched on this topic a bit, but I just want to ask explicitly because as with every issue we ever talk about on this podcast, this is inherently worse for people of color and those that are at the intersection of gender and another marginalized group. So, I'm curious what you learned from

[00:34:45] Anna Stoecklein: Um, but one thing in particular, you know, you all, was this through line in the book from BIPOC mothers and families about being both hyper visible yet invisible at the same time. Priscilla Osen talked about the difference of being [00:35:00] seen and being watched. Being scrutinized, but not recognized. So can you elaborate on that? What you kind of learned from BIPOC mothers and families about being hypervisible yet invisible?

[00:35:09] Jessica Hankey: This is Jessica talking. There are so many contributors to the book, so there's really a lot of different perspectives. And this is a topic that comes up in a lot of different ways. Some of the important ideas that were raised include questions about the visibility of women's lives, of their bodies, of the youth, and we might say innocence of their children, and here I'm thinking of the tendency to prosecute BIPOC children as adults, and to disproportionately criminalize disobedience among BIPOC children in school.

[00:35:42] Jessica Hankey: So you could say their disobedience is hyper visible, and their youth, that they are children, is not seen. And it's easier maybe to talk about written pieces in the book, but themes of visibility run through a lot of the works of art. And a few that come to [00:36:00] mind are works by Stephanie Suhuko, Carrie Mae Weems, Regina Jose Galindo, among others. And if I just were to start by talking about Carrie Mae Weems as one example, she has a photograph called Morning that's part of a project called Constructing History, and it shows three women seated on a pedestal, and they're dressed for a funeral. The central figure is wearing a black veil of mourning, and around them, there's the metal track that's used in filming to make a tracking shot, like a horizontal shot where the camera moves smoothly through space.

[00:36:40] Jessica Hankey: So, to me, this photograph evokes what Jennifer Nash talks about in her conversation with Sophie, which is the hyper visibility of Black maternal grief within the culture, and what's less visible, what's less explored perhaps, is maybe their joy, [00:37:00] or also the ambivalence they might feel about the immense pressure that they carry.

[00:37:05] Jessica Hankey: In a different work by Regina José Galindo, she looks at the often hidden incarceration of undocumented families. And we did hear a lot more about this under Trump, but it had been going on for years in the United States. For her performance in 2008, which took place in Texas, she rented a cell from a company that supplies private prisons and she moved in with her husband and daughter for 24 hours into this prison cell and then exhibited the cell for the duration of the show.

[00:37:36] Jessica Hankey: So, invisibility is so important to the carceral state, right? People are imprisoned and they disappear from public life. The prisons are located often really far away from towns and cities. So we don't see the prisons and we don't see the prisoners. And yet in many cases, as many of the contributors point out in the book, it's the extraordinary [00:38:00] scrutiny of people of color by the state, and it's institutions that lead to incarceration.

[00:38:04] Anna Stoecklein: So, I mean, we can all start to deduce why this is so important, but you do end the preface saying the study of surveillance in our daily lives has never been more urgent. And, I mean these examples that you just gave, Jessica, are exhibit A, B, C, D. I want to ask, you know, why, why is this an urgent issue and where do we go from here and what needs to happen for this to change?

[00:38:33] Sophie Hamacher: I think this is such an urgent issue because surveillance has implications for equality and it has implications for justice. To look closely at surveillance is really an attempt to understand the very quickly increasing ways that we are being watched. And this is not only limited to data tracking, but can also be applied to all sorts of things as we see really see in the book.

[00:38:58] Sophie Hamacher: I recently read an article about [00:39:00] how AI is revolutionizing how governments are watching us, for example. In George Orwell's 1984, there weren't enough people to watch all the surveillance cameras all the time, but AI can watch all of the surveillance cameras all the time. So all of these changes, all of these technological changes are going to really impact how we interact with one another.

[00:39:25] Sophie Hamacher: I think that's why it's such an urgent topic. So what we're really trying to do with this book is move from the individual experience to systemic policies to see how our struggles are connected. So the way we live today is directly influenced by surveillance. We are a surveillance society.

[00:39:45] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely And something else that jumped out to me and that we kind of touched on in the beginning, is this idea of community. You know, this was a through line throughout the book, [00:40:00] but the contributors, especially BIPOC women, talk about the importance of expanding our ideas of mothering.

[00:40:06] Anna Stoecklein: So there's everything that you just mentioned. There's raising awareness like we talked about, but there's also this idea of expanding our ideas of mothering, of family, and of how we care for one another. So why do you think that's important or how does that tie into how we progress forward from here?

[00:40:21] Sophie Hamacher: I think that's, that's really important. And that's one of the questions that I was also asking the contributors of the round table which serves as the introduction to the book. I asked specifically about what we can learn from practices of community motherhood and how mothers can resist and create opposition strategy, strategies to state surveillance.

[00:40:44] Sophie Hamacher: Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who we mentioned earlier, had the most poignant answer and a really great example. She taught me about the sisterhood of Black single mothers in Brooklyn in the 1980's. Their revolutionary act was to [00:41:00] transform the Black single mother from a problematic individual in the eyes of both the state and the social community into a collective of experts collaborating on care.

[00:41:11] Sophie Hamacher: The person who knows best how to support a new black single mother is not the social worker, she said, or the political author of social policy, but simply another black single mother who has been a black single mother longer. So they redefined themselves, this sisterhood, they redefined themselves as motherful, an abundant community of mothers moving beyond the isolation of stigmatized individuality.

[00:41:39] Sophie Hamacher: You also asked why expanding our ideas of mothering, of family and of care for one another is important. I think this expansion is imperative, especially in the U. S. because the state doesn't support us. In Biden's Green New Deal, there is no money for child care or education. I can hardly believe that.[00:42:00] All of the systems here are really broken, and the book takes the stand of resisting a government that provides no help when it comes to reproductive health care or child care, resisting the fact that there is no social welfare system.

[00:42:15] Sophie Hamacher: Resisting, that during the last presidential election, there was only one candidate that even brought up child care in the first place. Resisting a country that doesn't respect care work, or children for that matter. That is why expanded care is so important. We really need more of it across the board.

[00:42:34] Anna Stoecklein: Only one presidential candidate that brought up childcare. Wow. Yeah, so, content of your work, everything we've talked about, this can be quite grim. But, imagining and fighting for a better future, you have to have a bit of hope. Or else, you can't be in this work in the [00:43:00] first place. So, what keeps you hopfeul?

[00:43:01] Sophie Hamacher: Breaking down the nuclear family and finding alternative models to live. So the models that I just spoke of, the models that I learned about from others within the book, speaking to other mothers, the models of other collectivist mothering, that gives me hope. And, just thinking about the conditions that inform and ground our caretaking practices also gives me hope because they have such profound implications for taking care of others and of ourselves.

[00:43:34] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, seeing that there's other ways of doing it. What about you Jessica, anything that keeps you hopeful?

[00:43:38] Jessica Hankey: Yeah, it is grim, as you said, and there are things that keep me hopeful. Collaboration and dialogue give me hope. The work of the contributors gives me hope. To launch the book we collaborated with the artist Viva Ruiz, who started the collective Thank God for Abortion, and with her we [00:44:00] threw dance parties and even a roller skating dance party to raise money for reproductive healthcare, so abortion providers and a community midwifery practice.

[00:44:13] Jessica Hankey: And that gave me some hope, and I think we need events like that to help us recharge for the fight ahead. So yeah, I see a lot of cause for hope.

[00:44:22] Anna Stoecklein: Love it. I'm glad, glad to hear it. We're getting to the end of our time together today. Is there anything else that either of you would like to talk about?

[00:44:36] Jessica Hankey: I've been thinking recently about when U. S. Senator Tammy Duckworth made history because she brought her infant daughter to the Senate floor for an important vote. That was in 2018. And the Senate actually had to pass a resolution allowing her to do it. It took months and there were all kinds of debates about what the baby would [00:45:00] wear, would it wear shoes? How many babies could there end up being in the future on the Senate floor during a vote? And would that be a problem?

[00:45:09] Jessica Hankey: And she was the first senator in US history to give birth while she was in office. And it just starts, you know, it's just thinking about the ways that motherhood and parenthood and child rearing is sequestered and kept out of public life.

[00:45:26] Jessica Hankey: And... Just I think the implications of these efforts to bring the activities of mothering and anybody can mother, right, people of all genders can mother as a verb. To bring the activities of mothering into public space, I think, has a lot of potential for changing the views of parenting in our culture, right?

[00:45:49] Jessica Hankey: And for having it be that there's not just one presidential candidate talking about childcare as part of their platform. I

[00:45:57] Sophie Hamacher: I think the one thing that I would [00:46:00] add is that we, the time that we invested in creating this book, we worked on this book for five years. I think this time and the accumulation of interviews and perspectives echoes the work of political activism for us, in terms of the work is never over and organizing is hard and it takes a lot of dedication.

[00:46:20] Sophie Hamacher: I think the conversation that we've had today has really only begun to scratch the surface of what the book contains. And I really hope that our listeners today can take a look at the book.

[00:46:32] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, definitely barely scratches the surface. I second that. Well, if people take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:46:47] Jessica Hankey: I think about books like Of Woman Born by Adrienne Rich and This Bridge Called My Back, which is an anthology edited by Gloria Anzaldua and Sherry Moraga. And the effort to just [00:47:00] radically reimagine how society might be organized and ask these bigger questions. And our book, I think, is contributing to this project, and I hope it generates more conversations about how we want to live and support one another. I hope that's what people take away.

[00:47:17] Sophie Hamacher: I echo that. I think that was well said.

[00:47:21] Jessica Hankey: Thanks, Sophie.

[00:47:23] Anna Stoecklein: Amazing. Sophie, Jessica, thank you so much for your time today, for starting in some ways and continuing on this conversation that is urgent and important and for putting this work out into the world. Thank you.

[00:47:41] Sophie Hamacher: Thank you so much, Anna.

[00:47:42] Jessica Hankey: Thank you so much.

[00:47:43] Sophie Hamacher: It's been a pleasure talking to you.

[00:47:45] Jessica Hankey: Yeah, it's been great.

[00:47:46] Section: Outro

[00:47:47] Anna Stoecklein: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one woman operation run by me, Anna Stoecklein. So if you enjoy listening and want to help me on this mission of adding woman's perspective to mankind's story, be sure [00:48:00] to share with a friend. One mention goes a long way. Hit that subscribe button so you never miss an episode and make sure to rate and review the podcast while you're there.

[00:48:10] Anna Stoecklein: For more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes, follow The Story of Woman on your social media platforms. And for access to bonus content, ad free listening, or to have your personal message read at the end of every episode, consider becoming a patron of the podcast. Or you can buy me a one time metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs and helps me continue to put out more and better episodes. In exchange, you'll receive my eternal gratitude and a good night's sleep knowing you're helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.