[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Anna Stoecklein: Welcome to Season 3 of The Story of Woman. I'm your host, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:00:05] Anna Stoecklein: From the intricacies of the economy and healthcare to the nuances of workplace bias and gender roles, each episode of this season features interviews with thought leaders who provide fresh perspectives on critical global issues, all through the female gaze.

[00:00:20] Anna Stoecklein: But this podcast isn't just about women's stories. It's about rewriting our collective story to be more inclusive, equitable, and effective in driving change. It's about changing the current story of mankind to the much more complete story of humankind.

[00:00:37] Section: Episode introduction

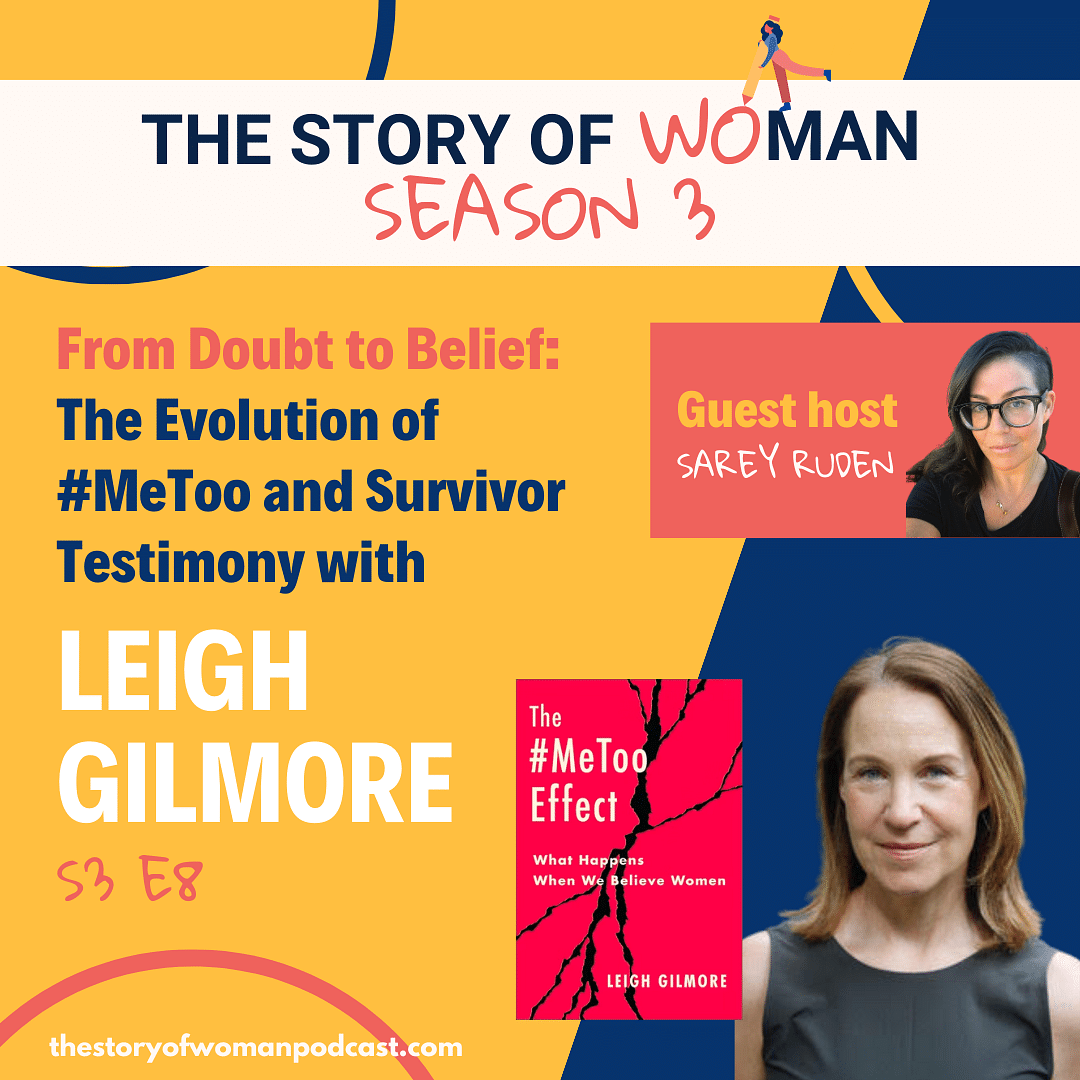

[00:00:38] Anna Stoecklein: Hello, and welcome back. Thank you so much for being here. We've got another guest host taking over today. The last one of this season, Sarey Ruden. A Detroit based artist, Sarey Ruden's project, Sarey Tales, is a collection of artwork inspired by the creepy, cruel, and misogynistic [00:01:00] messages she's received from men during her online dating journey. By transforming the unsolicited messages she receives on dating apps into fearless and provocative works of contemporary feminist art, Sarey hopes to reframe the conversation around gender based digital abuse.

[00:01:15] Anna Stoecklein: What began as a fun project coming up with clever designs from cruel words turned into something larger. Sarey's art is sold in boutiques, pop up shops, art fairs, and subscription boxes reaching thousands of people globally. Her work's been included in gender study courses at several universities, as well as in research papers, focusing on feminism and modern art. She's participated in international art shows with even more events and collaborations on the horizon. Sarey Tales has become more than a concept, it's become a movement.

[00:01:47] Anna Stoecklein: And this is why I thought Sarey would be a fantastic person to speak with Leigh Gilmore about her book, The Me Too Effect: What Happens When We Believe Women. I absolutely fell in [00:02:00] love with Sari's project and her art when I first saw it on Instagram. Yeah, I'm so happy that she was the one who had this conversation with Lee. It's incredible and I think you're really going to enjoy it.

[00:02:13] Anna Stoecklein: And as I've mentioned in past episodes with the guest host, I have ideas of continuing to expand the podcast to include voices of women and people who know more than me than certain topics or come from different backgrounds and lived experiences. So this is kind of the beginning stages of that idea coming to life. So I'd love to know what you think or if you have any ideas or if you'd like to guest host yourself, please get in touch.

[00:02:40] Anna Stoecklein: But for now, please enjoy this conversation with Sarey Ruden and Lee Gilmore, starting with a quick introduction from Sarey about their conversation.

[00:02:49] Sarey Ruden: I had the pleasure of interviewing Lee Gilmore. She's the author of a new book called The Me To Effect: What Happens When We Believe Women. Lee is a scholar of life writing and feminist [00:03:00] theory, as well as the author of several other books and articles on trauma, feminism, and the law. She is currently the visiting professor of English at The Ohio State University.

[00:03:10] Sarey Ruden: When Anna asked me to interview Lee after reading her book, The Me Too Effect, a few months ago, um, I really didn't know what I was getting into, and I didn't know what a treat it was going to be to read this amazing piece of work. Like most of you, you probably came to me too with the idea that this was a moment in time about six years ago that happened, and it was a breakthrough moment where people started believing women and men were held accountable for their actions.

[00:03:35] Sarey Ruden: And it is... mostly, you know, true, but there's so much backstory and feminist lineage that leads up to how the MeToo movement actually came to evolve into the tipping point of what we associate with it now. From the different women whose voices led to the formation of the basis for me to to all the converging stories voices and different narratives[00:04:00] throughout our culture and throughout time that have basically culminated in the tipping point of MeToo.

[00:04:05] Sarey Ruden: Lee obviously is a very accomplished writer and scholar, and I was very intimidated to interview her, but I really enjoyed it so much, especially as her work kind of paralleled a lot of the work that I do with Sarey Tales, which is my personal project that I kind of think, has a lot of similarities with the MeToo movement.

[00:04:30] Sarey Ruden: One of the things from the book that really struck me is this idea of the public exposure of private pain, and that's really what I think brings a lot of people into the movement where it's like showing this side of women's and men's experiences that is typically kept private in the private sphere, but then it's made public.

[00:04:50] Sarey Ruden: So these allegations of sexual assault and harassment and rape that are usually things that are kept on the personal level are being exposed publicly and it's that reframing [00:05:00] of this pain basically that I think is so inspiring and draws people in. And that's really what I do unintentionally with Sarey Tales is sharing these messages that I get and other women get from men and dating apps and bring them into the public sphere. It's really shocking when you see things that really, you're supposed to be kept hidden.

[00:05:21] Sarey Ruden: Also the idea of reframing the default narrative of believing men. And that's really what the crux of this whole movement, the Me Too movement is about, in my opinion. Our default narrative in our culture, in society is to doubt women and to give men the benefit of the doubt. And why is that?

[00:05:37] Sarey Ruden: And she really goes into the history of the patriarchy, and how this forms this bias that we don't even realize we have. And I really encourage you guys to take some time and listen to this interview, because Leigh is just a brilliant woman. And the things that she spoke of really made me think about Me Too movement and other feminist movements in a completely [00:06:00] different perspective.

[00:06:01] Sarey Ruden: I hope you enjoy listening as much as I did asking her some questions and getting to the idea of what happens when we believe women.

[00:06:10] Section: Episode interview

[00:06:11] Sarey Ruden: I'm really excited because I'm just, I love your brain and I love what you wrote, so I'm

[00:06:15] Leigh Gilmore: Oh, thank you so much. Thank you. I'm, I'm happy to be here.

[00:06:17] Sarey Ruden: Yeah. Okay, so this is Lee Gilmore. She is the author of the new book, the #MeToo Effect: What Happens When We Believe Women. And, Lee, I'd love to hear just a little bit about your background and how you got to where you are.

[00:06:32] Leigh Gilmore: Well, I'm a very recently retired professor of literature and gender studies, and I'm now Professor Emeritus at Ohio State. And my areas of expertise are literary criticism, life writing, especially US focused and feminist theory. And I draw on that expertise to examine the relationship between a range of cultural phenomena like the law and doubt, trauma, judgment and [00:07:00] literature.

[00:07:00] Leigh Gilmore: And given that the New York Times seems determined to declare the death of the humanities on its op-ed pages pretty routinely, I think it's really important to highlight how much the humanities can assist us in understanding what's going on in the #MeToo movement, that it enables us to bring both historical context and the tools of close reading and close listening to look at really complicated phenomena that are absolutely on the move.

[00:07:30] Leigh Gilmore: So instead of getting caught up in just the breaking story that's being delivered to us every day, I use my expertise as a humanities scholar to find ways to frame that fast moving phenomenon within longer traditions that help to sort of explain not only how we've gotten here, but how far we might go, which I think is always the question with feminist activism, is can we do more with it while there's momentum?[00:08:00]

[00:08:00] Sarey Ruden: Yeah, I think the idea of drawing on the lineage of feminist movements really explains, I really liked how you had that incorporated into your book because a lot of people, me included, it's just #MeToo, we only became aware of it when it was in the news or in the media, and don't even realize that it has been around for so long, the components that allowed it to reach that breakthrough moment.

[00:08:20] Sarey Ruden: And before we even get into more questions that I have, I want you to just, if you could explain a few of the key terms or concepts that you write about in your book. For example, narrative activism is a very, like big component of what you write in your theory. So I'd love for you to just explain that for our listeners.

[00:08:36] Leigh Gilmore: Yeah, so I define narrative activism as storytelling in the service of social change. So, narrative doesn't necessarily need to do that to shift attitudes about sexual violence. But it can filter into people's everyday consciousness through a range of stories that kind of shift our sympathies and our [00:09:00] awareness and our sense of who deserves care and who deserves attention.

[00:09:04] Leigh Gilmore: So an author doesn't need to be explicitly writing a book, an essay, a poem with a purpose of affecting social change. So narrative, activism as a culturally available form, is something that survivors have used to join with this lineage of shifting attitudes through how stories can be told differently.

[00:09:28] Leigh Gilmore: And I really saw that happening in the #MeToo movement, that the discussions of how to solve, prevent fix, sexual violence had gotten stalled in the courts, and that the courts as a kind of ultimate arbiter of harm and redress for survivors hadn't progressed. And in fact was sort of where complaints went to die.

[00:09:50] Leigh Gilmore: And, the storytelling offered something really different, and it offered, in that particular moment in 2017, what I saw as [00:10:00] the #MeToo effect. And the #MeToo effect, as I, you know, sort of watched it unfold, struck me as involving two key components. One was that it took all those isolated, disparate, individual stories of pain and it brought them together, they sort of coalesced. They all were telling something that could be understood as part of the same story. Not identical, right? Not interchangeable, but related. Related in a description of how the harm had happened, how it was being enabled.

[00:10:35] Leigh Gilmore: So that coalescing of individual voices into a collective witness enabled then the sort of second part of the #MeToo effect, which I think is really momentous, which is the shift from doubt to credibility for survivors, and the shift from impunity to accountability for abusers and the institutions that had enabled them. And that was sort of like gravity reversing.

[00:10:58] Sarey Ruden: Write that [00:11:00] in your book. I specifically remember that line. It's that shift, that reframe, that flip, that really, um, that's the groundbreaking moment when everything changes.

[00:11:09] Leigh Gilmore: Just to pick up on what you're saying, it, it wasn't that in this new formation that suddenly we had to suspend all ethical judgment, all of our sense of, you know, like skepticism. It just meant that any survivor is potentially credible, potentially reliable, potentially authoritative, instead of by default lying, right, and that's what we had before.

[00:11:35] Leigh Gilmore: We had, in place of the #MeToo effect, we had centuries of the common, the allegedly common sense formation of he said, she said, the sort of false equivalence between, she said it was rape and he said she's lying. Right?

[00:11:50] Leigh Gilmore: You know, and it doesn't even dispute what happened, right? So often he agrees that there was a sexual encounter but he says that what the problem [00:12:00] is that she misinterpreted it. He says she actually consented, she's wrong, and that's too bad, but he doesn't admit to rape. So that really changed in #MeToo, and the disruption was quite profound. And I think that the breakthrough of that, just replacing doubt and shame with potential credibility enabled lots and lots of people to say, well, it looks like there might be something here and I think we should let it play out. That was very different. That kind of suspension of default judgment, the kind of permission for survivors to speak in their own words, in their own time, in their own fora, that changed.

[00:12:49] Sarey Ruden: Yeah, that's a really interesting point, and I you find it in everyday life with everything. The default is believing men. The default is doubting women, doubting marginalized voices. In my own work with, [00:13:00] when men send messages to women, on dating apps, for example, the default is to say, there's no way that he said this. There's no way that people would act that way to somebody that they don't know spec, especially.

[00:13:10] Sarey Ruden: Even when there are screenshots showing that this is what happened, the default is always to say, well, maybe you did something that made him say this or write this. So the default is always doubting the woman and just supporting what the man thinks. And I think that this, this rupture as you mentioned, like this moment where the past kind of ruptures into the present where there's all these different voices and collective experiences that they come through into the present.

[00:13:36] Sarey Ruden: And that was an interesting theme, I thought it was temporality, is something you mentioned and that really struck out to me this concept of time and temporality. I'd love for you to explain that and how that kind of impacts #MeToo, or intersects with it.

[00:13:48] Leigh Gilmore: Yeah. And before I jump to there, Sarey, I just wanna pick up on two things you said. One is your own incredible work in sharing these messages that you've received. And I [00:14:00] see that as a really important gesture because when people who don't wanna understand the reality and the harm of sexual harassment, abuse, and violence, it protect themselves with a kind of plausible deniability. They say, it wasn't that bad. Maybe you misunderstood.

[00:14:22] Sarey Ruden: Or it happens all the time, is the other thing that you, yeah.

[00:14:25] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. And so we're conditioned through, as he said, she said, to direct care and sympathy more often to abusers than to those who are survivors. And one of the things that shifted in #MeToo, and that's evident in your work as well, is that a lot of stuff that had really been held at the threshold, there's stuff that we just didn't wanna listen to or look at or know about fully, came rushing into the public sphere.

[00:14:50] Leigh Gilmore: And what we heard, instead of, she said it was rape, and he said she's mistaken, is we heard what he said in his own voice, in his own [00:15:00] words. And then we had a context for understanding that as harm. So work like yours, puts that on the table and it removes this kind of euphemistic cloud. That we allow sexual violence to kind of hide within, we'll say, oh, you know, you have a crappy boss. You have a le

[00:15:22] Sarey Ruden: Right an individual, versus systemic and cultural.

[00:15:24] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. Yeah. So, so this idea of temporality, I wanted to come up, you know, as a literary scholar and a feminist theorist, with some explanation for what had happened in this massive reframing of sexual violence from not that big a deal to an urgent problem that required a structural solution.

[00:15:47] Leigh Gilmore: And I came up with several elements that coalesced, they clicked into place in the #MeToo moment. And I call that a breakthrough. And I use that to distinguish [00:16:00] between the word that was used all the time, which is, this is 'unprecedented'. So if you listen to, you know, you read any article, you listen to the news, the lead line is in an unprecedented outpouring of, of stories of sexual violence. We all are now listening. This is unprecedented. We can't believe it. It's never happened before.

[00:16:16] Leigh Gilmore: And, you know, my work had already enabled me to know that that certainly wasn't true, that survivors had been telling these stories, you know, forever. But it was just that no one had listened. So what we needed to come up with was an account for what changed in the hearing of sexual violence.

[00:16:36] Leigh Gilmore: And so I identified the elements of saturation, right? So just like a ton of sexual violence. And I think you can readily stipulate that lots and lots of people know that there is a tremendous amount of sexual violence because you can ask people to quote statistics and most people will be able to come up with something and they might say one in three, one in six, [00:17:00] people will be sexually assaulted, so there's this sense of saturation, so lots of.

[00:17:06] Leigh Gilmore: And then that shifts to the sense of it's too much, right? So something happened with saturation. It wasn't just what's going on. It was the new knowledge about it that came from the perception of it from survivor's points of view. So this new meaning of saturation, not only a lot, but too much, catalyzed visibility so that sexual violence became visible as what survivors describe it as being, which is harmful, long lasting throws you out of your life, derails you, forces you to catch up while other people speed ahead.

[00:17:41] Sarey Ruden: Yep.

[00:17:42] Leigh Gilmore: Then in the presence of those two elements, a wide audience, a diverse global audience who had previously been comfortable permitting this to happen suddenly wanted to participate, they shifted their own attitude. So this new information was [00:18:00] processed as knowledge that needed to be acted on. So there may be more elements than saturation, visibility and participation, but I am persuaded that those are the ones that happened during #MeToo.

[00:18:14] Leigh Gilmore: Those elements might be present in anything that resembles a breakthrough where something that is a longstanding historical problem becomes visible to a new broad audience as something that requires their action to change it. So, you know, you could see that in the outpouring of pandemic protests after the killing of George Floyd. Those same elements lock into place. I don't know how to make those come together, I...

[00:18:41] Sarey Ruden: It's like something going viral, right. You don't know, but it's like a chemistry experiment. I feel like the way that you're explaining it, like you have these elements and they, like one thing catalyzes another, and then they, there's an explosion and..

[00:18:53] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. That's what I think that helps to, that maps onto what so many of us felt. It's like, is this really [00:19:00] happening? This is seems to be really happening. What's going on and how can we keep it going?

[00:19:05] Sarey Ruden: Right. Right. And so that is the question, how do we, uh, like capitalize on this momentum? For instance, I know with all like the, the racial reckoning in 2020 with George Floyd, like you brought up, I feel like there was a lot of momentum and now it's almost like it's been forgotten. And not by everybody, but by mainstream media and by the way that it was picked up in social media. So like how do we keep momentum of #MeToo going? And you think it is, has it changed? I mean, is it just part of our culture now?

[00:19:30] Leigh Gilmore: So yes, I think it is part of our culture now. I think that forever after a marker was thrown down and reframes all survivor testimony as potentially credible.

[00:19:45] Sarey Ruden: Mm-hmm.

[00:19:45] Leigh Gilmore: And that, so far, that seems to be sticking. So it offers any survivor the opportunity to frame their account within that context to say, [00:20:00] this is, or sometimes this isn't, a #MeToo story.

[00:20:04] Leigh Gilmore: And when they say that, what they're saying is it should be heard within that context, within a context of demanding accountability for abusers and institutions. And I think that has stuck. Now since #MeToo wasn't like a Supreme Court case, it didn't change laws overnight, and it has a kind of vague antagonist, you know, patriarchy. So you can't really like protest and mail letters to, to patriarchy and shut it down. Yes, yes.

[00:20:35] Sarey Ruden: I really like that idea.

[00:20:36] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. So many people said, um, two weeks into October and as early as November, 2017, people were already proclaiming that #MeToo had gone too far. And also that it was dead.

[00:20:49] Leigh Gilmore: So the desire to write the obituary on #MeToo has been present since its beginning. And that's really just a very familiar story about the co-evolution [00:21:00] of the forces of doubt and discrediting and any kind of social progress. So it's not like #MeToo would kill pariarchy.

[00:21:09] Sarey Ruden: Mm-hmm.

[00:21:10] Leigh Gilmore: Or that Black Lives Matter would end white supremacy. The antagonist is too establish and too big and too mobile, but that doesn't mean that that tool wasn't massively effective. And it changes generationally how we think about what we owe to survivors. It challenges both how we think about the past, which is very important. And how we think about the future and how we think about the future is something where I think survivors really guide us.

[00:21:45] Leigh Gilmore: And it's why I find that it is such an ultimately hopeful and enabling genre of literature and genre really, of everyday storytelling, which is that survivors focus on, [00:22:00] 'what's next?' They focus on what happened, what's wrong, who did what. But they rarely ask for more policing, more criminal legal intensity to be directed at abusers or institutions. They ask for very different things. 'cause sort of like in the aggregate, right? Again, not taking away anybody's individual experience of maybe very much wanting those things, and certainly not letting the law off the hook.

[00:22:32] Leigh Gilmore: But what survivors ask for again and again, first, fair and transparent reporting processes, like, how do I tell this story? So instead of these kind of kafkaesque processes that ensnare complaints, and complainers and ultimately consign them to silence as the clock ticks on statutes of limitations. So instead of that, and instead of the [00:23:00] appearance, the fake appearance of a fair process, an actual fair and transparent process, okay?

[00:23:07] Leigh Gilmore: Then independent third party fact finding, right? So not trusting those who are accused of, or, and not, not trusting them with carrying that out, but also not tasking them with that. Instead coming up with, kind of fact checking entities that can credibly render a view of the case.

[00:23:28] Leigh Gilmore: Instead of relying upon stereotype, status and reputation, to guide a sense of who should be heard and who should be sacrificed, follow the facts. When those facts in that investigation lead to a finding of responsibility and fault, than what survivors typically want is for that to be made known.

[00:23:50] Sarey Ruden: So it doesn't happen again, right, so the reproduction of this is halted.

[00:23:55] Leigh Gilmore: That's exactly it. So it stops the cycle. And then for [00:24:00] proportional penalties to be levied. And just that not like they should go to jail or there should be, you know, any number of harsh, punitive measures because survivors typically detach through their healing from a tight relationship with abusers and abusive entities, that those begin to lose their grip on the psyche and health of a survivor as the community restores the survivor to itself. Right?

[00:24:39] Leigh Gilmore: And so that's the power, that's embedded in something like restorative justice, is that survivors don't typically seek an apology from an abuser. It's not clear that those would be heartfelt or meaningful, but instead to be restored to the [00:25:00] community where the harm was allowed to happen. And so whether that is a workplace, a family, an educational institution, but that taking of responsibility and that kind of public process is more frequently what survivors ask for.

[00:25:16] Leigh Gilmore: So I do think that there is a view of the future that comes from this. You know, so many people were quick to say, what about the men? You know, this is horrible that they've had to sit down for a minute, and men, there're being, I'm using that loosely. And what I mean is those who have abused others, abused their power and abused others and benefited from that.

[00:25:36] Leigh Gilmore: So, our concern and our care for what happens to them suggests that the weighing of the harm of sexual violence, there's still too much stuck within an abuser centric epistemology. Like, what does it mean for them? We can't really think outside that, you can't hold him accountable forever, you could ruin his life, you know, people can readily [00:26:00] supply a lot of reasons to care about the men. In contrast to a real blank, when you ask them, well, what do you think we owe survivors? What do you think we should do next?

[00:26:14] Sarey Ruden: Yeah, again, flipping reframing that from the survivor's point of view can change everything. I was also struck with something you wrote that sexual violence is the only crime in which we doubt that something actually happened. Like if someone says, oh, I was robbed last night. You don't say no, you weren't. Like you, you give them the benefit of the doubt and investigate why is it with sexual violence or rape or harassment, that it's always, there is doubt that that is the initial reaction?

[00:26:43] Leigh Gilmore: Yeah, I think that's a, that's a great example, right? You know, it's like if you are struck in a hit and run. Nobody says, were you wearing a target? You know, that, there's a very swift and, and I would say unconscious because conditioned shift of sympathy away from [00:27:00] victims, it's shifts rapidly.

[00:27:03] Leigh Gilmore: And we give abusers the benefit of the doubt because we take it away from victims. It's like this zero sum game. And it's very long standing so it also requires kind of a big solution, including becoming aware of how it operates. This doubt is sort of, um, a positive artifact of the enlightenment.

[00:27:25] Leigh Gilmore: A kind of shift toward skepticism about authority, where authority is, you know, God pope's, kings, and to people to figure out with themselves and for themselves the meanings of tremendously important things. So, you know, we have internalized that as it's been carried on through our law, through culture, through everyday life as rational and good.

[00:27:51] Leigh Gilmore: So it feels good to doubt women, and I don't know how many times you've been in a conversation where someone will just be bringing up [00:28:00] a story of sexual harassment, dating violence, something that happens in the workplace, or that was really creepy and weird, but for which they're really struggling to find words to only to have it cut off. Are you, are you sure? Are you, are you sure? Like, maybe you got that wrong. Maybe it was something you said, maybe it started earlier with something you did, you know, that it kind of very rapid reframing to get things within um,

[00:28:28] Sarey Ruden: ...where we're comfortable that, that the status quo, right? Yeah. It's like that discomfort of maybe if, if it was different, what does that mean for everything? If the default becomes believing women.

[00:28:39] Leigh Gilmore: Yes, if the default is, and you know, I love the phrase 'believe women' because it replaces doubt all of them, you know, so that really makes a lot of sense. I write in the book about the phrase, believe all women is, you know, kind of a boogeyman invented by Barry Weiss. No survivor group ever said [00:29:00] that, right? I mean, we don't have to like become credulous people who say like, well, you know, whatever you say goes, I, I mean, I don't think that that helps survivors either.

[00:29:10] Sarey Ruden: Right, right. Because it diminishes the truth. We don't need to do that. Like we don't need to say, believe every single woman, like believing some women and giving the women the opportunity to be heard is what all we need.

[00:29:22] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. And as you say it, those words are so powerful. That's all we need. That's all survivors are asking for, is don't deform and freight down the already terrible experience with an aftermath characterized as a revictimization. You know, it's a new chapter in the abuse and we don't need to open a new chapter in abuse.

[00:29:50] Leigh Gilmore: And so doubt sort of hounds women whenever they speak out in public or in private, because it's our default setting. We see women [00:30:00] as unreliable, as sinful, as associated with shame, as dangerous to men.

[00:30:07] Sarey Ruden: Do you think that's from like Adam and Eve, even like back from that? Like that's just like that initial like evil?

[00:30:13] Leigh Gilmore: Religious traditions often use gender as a framing of who is authoritative and who isn't. Who has credibility, who doesn't, who counts, who's lesser, you know, so yeah, absolutely. Religious traditions weave that in the law. It's woven into the law. It's woven into all of our institutions...

[00:30:34] Sarey Ruden: It's insidious. It's when you can't even unsee it once you understand that, that it's in the foundations of everything we believe.

[00:30:41] Leigh Gilmore: And it helps to explain why survivors feel shame. It explains how effective the threat no one will believe you is because that's something you can observe in daily life and may even feel it about [00:31:00] yourself. And so the internalization of those harmful forms of bias show us how important it is, how very beneficial it would be if we were to rethink that from survivor's perspective and reframe it as an unhelpful standard of judgment and an unhelpful guideline for justice. And think instead of what survivors ask of us, which is to listen.

[00:31:29] Sarey Ruden: Absolutely. The internalization of this because of cultural norms, it's also the idea of self-policing. What I have found, like not even in just not wanting to go to the authorities because you know that they're not gonna help, but it's also when you're sharing your story, understanding that you probably will not be believed.

[00:31:49] Sarey Ruden: Like I've experienced this with my work with Sarey Tales and my art. It's not just uh, reporting the men who send these messages to the dating platform, the app, they ignore you, [00:32:00] but when I share them or when they are shared publicly the vitriol that me and other people who share this type of work get back is so overwhelming in defense of the perpetrators that it's just you begin to self-police and you begin to not share.

[00:32:14] Sarey Ruden: And when you stop speaking up and stop sharing, and then the collective stories like everyone, as you mentioned in your work, like all these collective voices of the aggregate of these stories, that is where the power is when you have all these voices coming together. And as soon as we start policing ourselves, then there's not even an opportunity to be heard. And that's like, I think the biggest shame is that the silencing of ourselves.

[00:32:37] Leigh Gilmore: I was listening to one of my favorite podcasts, Amicus with Dahlia Lithwick, who whom I adore and admire greatly. And she was interviewing Roberta Kaplan and E Jean Carroll. And at the end of the podcast Dahlia Lithwick observed that what we really, really need is to multiply attorneys like, Roberta [00:33:00] Kaplan. And E Jean Carroll said no. I mean, although having powerful and effective and committed advocates is super important. But she said, no, it's to collectivize and empower the survivors. And advocates, activists, attorneys are invaluable, without whom real change is slow and impossible.

[00:33:22] Leigh Gilmore: But the #MeToo effect enables all survivors to see each other in relation to each other. And the fragmenting on social media of that process by mobbing and bullying, by bots, and by monetized YouTube users, which we saw very to horrible effect in the Amber Heard Johnny Depp Defamation trial, that those kind of online publics can be created through very cynical means and mobilized to benefit [00:34:00] those who are directing hate and harm further at survivors.

[00:34:05] Leigh Gilmore: That shifting of the focus toward an assembly, not to create an echo chamber, but to silence the other shouting down forces, that I think, is difficult to maintain and it suggests why any kind of social media campaign is always a slice in time, right?

[00:34:26] Leigh Gilmore: It's like this happened in this moment. It can be carried on, you know, on Twitter through hashtags, which kind of create the citation change in which enable these organic feminist publics that arise around particular campaigns to link to each other over time and for other kinds of stories to come out. Facebook is a longer form, doesn't have a word limit. Many people shared their accounts there, people who were telling their stories for the first time. And so to the extent that that capability of social [00:35:00] media exists, survivors can use that. But in hostile forums, where survivors don't have a guarantee that a forum will even entertain the possibility of their truth telling, then they're at risk.

[00:35:17] Leigh Gilmore: And so, for that reason several people have written Tanya Serisier is one person who's written very powerfully about this, that it's not ethical to demand that survivors speak out in general, right. This idea that some people have internalized, that all survivors must or ought to tell their stories, I don't think is a legacy of #MeToo.

[00:35:40] Leigh Gilmore: I think that that is too closely connected to the demand to expose yourself to harm, ridicule and shame and thereby diminish the power of your person and the power of your voice, rather than a lifting up, and a collecting and [00:36:00] a connecting of those stories within a, this kind of testimonial framework where you hear them not as one more sorted story of he said, she said, but instead as this truth telling exercise, that needs the context in which it makes sense for it to move forward and do the work in the world that is so necessary for it to do.

[00:36:24] Sarey Ruden: Yeah, the way you spoke that, it reminds me something you wrote, how it's not just the initial pain and trauma of the abuse, but then it's being re-traumatized through the judicial system and through the courts and through public opinion, and it's constantly being doubted over and over again. That is incredibly traumatizing and harmful to survivors.

[00:36:45] Leigh Gilmore: In the book, I offer several examples of that in the chapter on consent before and after #MeToo, I write about some memoirs and some court cases. And one of the memoirs is the memoir Consent by Vanessa Springora in [00:37:00] France, a very recent memoir. And she was groomed for a sexual relationship by a much older man, an important and famous writer, Gabrielle Matzneff.

[00:37:09] Leigh Gilmore: And he was a very publicly vocal figure about pedophilia, and it was kind of hiding in plain sight. You know, he is a, novelist who writes about what he calls seducing, which I would call raping children. And his patron was former President Francois Mitterrand, and he regularly appeared as important guest on literary and intellectual television programs.

[00:37:41] Leigh Gilmore: One of his tactics was to compel his young victims to write him love letters, which he would then use as evidence of consent. And when Vanessa Springora was able to finally extract herself from this [00:38:00] terrible situation she saw in a bookstore window, his most recent book, which had a photograph of her on its cover, and there was no relief in the law that would enable her to have that taken down.

[00:38:12] Sarey Ruden: Wow.

[00:38:13] Leigh Gilmore: She also came to understand, in a very personal important way, that there was no age of consent law in France, and so her memoir restarted the #MeToo movement in France and culminated in the first age of consent laws in that nation's history. So if we think about very specific examples of harm and the work that life writing can do, it's quite powerful because it takes the full context of the harm that is woven into someone's life, which is the focus of a memoir, right, is some aspect of your life is the focus of it, and it shows [00:39:00] the sort of insidious folding in of this harm into social networks, the kind of complicity of friends, family, and the society at kind of all levels to protect this right to abuse and to strip from victims this right to redress it.

[00:39:23] Leigh Gilmore: But, join together under this kind of me too movement, those individual stories can have a new kind of direction they can reflect back on not only, you know, what enabled all of you to seemingly exceed this in public and shift that to what kind of actual structural change might address that particular kind of harm, might start to cut the ties that connect this tissue together and make this net woven very tightly around victims?[00:40:00]

[00:40:00] Leigh Gilmore: And you know, what can we do to, in some ways free them, to prevent their perpetual ensnarement in these tactics and also to prevent others from being entrapped in similar ways. And they found that to be a very effective example when people ask, well, what can it do? What can a memoir do? Um,

[00:40:19] Sarey Ruden: Right, it's concrete solution.

[00:40:21] Leigh Gilmore: That's right. And you think for her, had it not eventuated in a change in age of consent laws, for her, it would have at least for once and for all, have put her stamp on the story and have been out there. That might only have been a, he said, she said without the transformative structural address of the change in the law.

[00:40:49] Sarey Ruden: That's so true. And that brings me to think about so the, with E Jean Carol, wasn't her case then possible because wasn't there something with the statute of limitations, like there's a law passed a couple years [00:41:00] ago where they extended it, you know, when you statute you limitation might have prevented somebody from bringing charges, now they were able to?

[00:41:06] Leigh Gilmore: Exactly right. So that is the law using the tools at its disposal to address a structural disadvantage to survivors and to offer a remedy in the law. And so in some jurisdictions, as with E Jean Carroll, the statutes of limitations for reporting are loosened. And it's usually just a window. It's like, okay, you've got in one year, three years, five years, you can bring forward this claim, right? So the clock starts ticking

[00:41:35] Sarey Ruden: Which is so crazy. I mean, even that it's like, it's better than nothing, but it's just you only have 90 days or one year, whatever to, you know, get all of your reporting in.

[00:41:44] Leigh Gilmore: So one of the things that I think is so interesting is the statistics that show under these conditions of silencing and under these conditions where there's no process for bringing it forward. You know, they are like what, how do you do [00:42:00] it when there's, you know, how do you do it, is a legitimate question. How long it takes for people to tell about abuse. And for children there's statistics I look at in the book is many tell the story for the first time after the age of 50.

[00:42:18] Sarey Ruden: I remember that.

[00:42:19] Leigh Gilmore: So if you think about the mismatch between a statute of limitations, when you look at that asymmetry, and then you ask simply who benefits, right? It's not the survivor. And if that's the tool in the law for them to seek redress, why is it set up so that it favors an abuser? Right, so all of the requirements that we demand of survivors in order to make their testimony credible, we also take away from them the opportunity to access those.

[00:42:55] Leigh Gilmore: You know, I think #MeToo has exposed that. #MeToo has really exposed [00:43:00] that the reality of the prevalence of sexual violence in people's lives, you know, sort of from the youngest ages into old age, just this sort of pervasiveness and prevalence, it's like the cat's out of the bag on that, everyone knows.

[00:43:16] Leigh Gilmore: But the institutional enablement, the structural disadvantage, that was hard to expose. But exposing those together I think is crucial to the #MeToo movement. You know, so when we talk about what it did, I am really anatomizing in this book what it did, right, how it exposed patterns and broke patterns.

[00:43:40] Leigh Gilmore: And I think a lot of people read probably Jodi Canter and Megan Twohey's reporting in the New York Times where they broke the Harvey Weinstein story. And Ronan Farrow's reporting in the New Yorker, where he broke the same story from the perspective of how Weinstein had been enabled to do it.

[00:43:59] Leigh Gilmore: And then they, [00:44:00] both of them published book form versions of the journalism that they had published Catch and Kill by Ronan Farrow, and She Said by Jodi Cantor and Megan Twohey. And together those books show both the impact of the collective testimony, what happens when survivors speak together.

[00:44:18] Leigh Gilmore: There's an epigraph I use in the book from the wonderful scholar and public intellectual Sarah Ahmed about when we speak together, we sound louder, we are louder. You know, this kind of stronger together, louder together, the amplification of #MeToo helps understand why when we went from, he said, she said to, we said, you know, that broke through. And then Ronan Farrow showed what survivors had to break through, the catch and kill policies where negative stories are not published and the protection of very, very powerful men by boards of directors and by those who [00:45:00] orchestrate payouts and nondisclosure agreements that I think there were a lot of people, you know, who said, what's a non-disclosure agreement, right? Or they said, I thought that was about intellectual property and people not taking proprietary information with them when they changed jobs, I didn't know it was to shut survivors up.

[00:45:21] Leigh Gilmore: So I think a lot of people kind of got a quick education on what survivors face. And it was that not only it was the sort of newly credible narrator of those experiences, the eyewitness authority who could tell about it, but it was what they were telling about, you know, that this wasn't a one-off, this wasn't a bad apple scenario. This was something really quite complicated, orchestrated, purposeful, knowing, and damaging. And those two books together, I think gave many [00:46:00] readers a sense of what survivors had been up against.

[00:46:04] Sarey Ruden: And speaking of survivors, do you have any advice, if somebody has experienced abuse or sexual violence, like at this point, what do survivors do? What tools do they have?

[00:46:14] Leigh Gilmore: That's a really good question. And there are national hotlines and national organizations to which people can turn. So, RAINN is one national hotline and one network that's trustworthy. There are rape crisis centers and clinics. You know, so when people are experiencing the immediate aftermath of such trauma, getting support early is very important, getting support and advice if people wanna go through the criminal legal system, it's a kind of supported tour through that, but understand that what makes sense for survivors is individual. You know, so, instead of, you should do this, or kind of blanket [00:47:00] advice, I think what many survivors say is most effective for them is if they are allowed to make their way in a supported way through a process on their own timeline.

[00:47:14] Leigh Gilmore: So there's no one size fits all, I think that's really important. That's something that the life writing about sexual violence, sexual harassment, sexual assault teaches us is that it happens to specific people in specific communities and in specific locations. That it's happening all the time to lots and lots of people doesn't mean that what will help someone will help another person in the same way or is even available. And so navigating to conditions of trust and support are crucial. Being heard is crucial.

[00:47:49] Leigh Gilmore: And so what I want to shift then, is the onus from survivors for figuring that out to institutions and communities, to laying that out and having that [00:48:00] ready. What are you doing as an organization right now, or have already done and have publicized to make it clear and safe to bring forward a complaint? What have you done? What are you doing, that's the question. Not holy cow, what should they do? You know, bad thing just happened. Who's gonna believe them? Where should I go?

[00:48:20] Leigh Gilmore: Like, all of that placing of the burden back onto, you know, someone who is traumatized and somebody who already in some ways has been let down by the situation and what's occurring in it, right? So in the book I talk about shifting our perspective from this dyad of the perpetrator and the victim, and to placing them instead within the sort of theater of participation so that we can understand how there are victims and abusers for sure, but there are also people who would never imagine [00:49:00] themselves as ever inflicting harassment or abuse on anyone who are nonetheless bystanders to it. Sometimes passive, sometimes deceptively unhelpful, that they promise help, but they don't offer help, that they enable the abuse, they minimize, they excuse, they tout the reputation of the abuser over the reputation and work life of the victim.

[00:49:28] Leigh Gilmore: Then there are people who are beneficiaries, you know, sort of like it or not, when people are harassed out of employment situation, out of educational situations, the queue gets shorter to the top. So there are those who are, perhaps as I've said, unwilling beneficiaries, but beneficiaries nonetheless.

[00:49:48] Leigh Gilmore: And so we need to understand that it's a coordinated response that's required, that the message goes throughout a particular culture, a work culture, a sports [00:50:00] culture, a religious organization, a family, a community, that the word goes throughout that violence, harassment will not be tolerated.

[00:50:10] Leigh Gilmore: And it's really important that that become one of the main goals in the mission of any entity. Organizations that are hospitable to sexual violence are notoriously and systemically tied to environments where racism, homophobia, and transphobia also thrive because those forms of bias are interwoven. So as much as we focus on women, on what happens when we believe women, the harm that women face, the disadvantage and structural inequalities that women experience in the law, it's really important to emphasize that survivors of all gender are discriminated against in the same ways.

[00:50:56] Leigh Gilmore: You know, not invariably and for every person, but the same [00:51:00] tools in the arsenal of bias and abuse that are directed at women are directed at all survivors. This kind of structural inequality and disadvantage, this use of bias and stereotype to ensure that the facts don't come out, that you persuading listeners to hear this according to their bias of who's trustworthy and who's not.

[00:51:20] Leigh Gilmore: And that's very important because when survivors of all genders bring forward claims of sexual harassment and are doubted, they experience the same shaming, everyone experiences the shaming and the silencing that comes with it, the turning inward and turning against oneself of focus that really should be an opening onto a process of healing and justice.

[00:51:46] Leigh Gilmore: And I say ought to in a just and fair world, I don't say that lightly. And I don't say that as if it were silly to want it or expect it. Because [00:52:00] absolutely it's opposite is what is being set up and carried out now. So if you can do that, you can do it differently. That's been the hope at the core of my life as a teacher for several decades, which is that if you are taught to do something in one way, you can be taught other ways of feeling, doing and knowing it.

[00:52:21] Sarey Ruden: Which seems so obvious, right, it's those simple things like that, that are so mind blowing that right, if you can be taught to do something harmful way, you can be taught to do something the helpful way.

[00:52:32] Leigh Gilmore: That's right and it requires collective understanding, collective knowledge, collective commitment, and collective carry through, you know is to think, instead of what about the men, to think about what do we owe survivors? This idea of obligation, I think is really important because we've shifted potentially, I mean, there's a sort of reframing from doubt to credibility, from impunity to accountability, and that enables us to ask new questions [00:53:00] and take new actions and steer down different paths.

[00:53:03] Leigh Gilmore: And one of the questions that can equip us to carry out that work is to ask, what do we owe survivors? What are our obligations, like ethically. Now that we know this, and now that we understand that there is a protective benefit for abusers, what do we owe survivors? And to keep thinking about that, to ask that in the contexts as they arise, not to get as caught up or focused on the past, right? Like, what about these great men in the past who did these wonderful things, but have these, you know, stains on their character?

[00:53:42] Leigh Gilmore: If you think that you can dissolve the complicity of the Republic of the United States by saying Thomas Jefferson was a slave owner and taking a few names off a few buildings, then I think you're gonna find that that's like a bandaid [00:54:00] on the problem. That what we need instead is, I mean, you can think through individuals and through specific cases, that's an effective way to focus any kind of inquiry, but the problems are bigger, right? And they're institutional and the solutions are often institutional as well, is a kind of accounting of what enabled that to happen, but how it still happening.

[00:54:20] Leigh Gilmore: So the notion of obligation focuses us on what happens next, what do we do now, you know, not to necessarily stop talking about what we did in the past, not saying that, but how we talk about that now is really important because new generations are listening and prior generations are testing whether they're being heard, right?

[00:54:47] Leigh Gilmore: So what are the conditions for making the world safe for survivors to speak out and to have that change things, right? So I'm much more interested in the message that comes from [00:55:00] survivors about what do we do next. And sometimes that means absolutely removing abusers from positions of power and preventing them from holding those in the future.

[00:55:14] Leigh Gilmore: And that seems to me to be fair, because it understands the longstanding harm to survivors and to the industries in which they are held up as exemplars. And for new norms to establish themselves, we have to be kind of in tune with the conditions of emergence in which this breakthrough happened. We are aware in new ways of the prevalence and the harm of sexual violence, full stop. No one can say they don't know.

[00:55:51] Sarey Ruden: Right. The context now is there, and you say the #MeToo movement, everyone knows what that means, and we have that frame of mind moving forward when there are [00:56:00] abuses that happen or reported. So, when I asked earlier, like, what happens to me too now, like how has it evolved, in a way that's not the right question because it's, it's never gonna go back to how it was like, we've already now established this new frame of reference, right?

[00:56:14] Leigh Gilmore: Theoretically we have, we have theoretically, and I think theory is really important. So theoretically we have, so we have that available to us. And I think part of the power of #MeToo was, it wasn't just like October, 2017 for the first time ever, survivors have spoken their truth and we're listening. So we're over, we've come of age about the unprecedented narrative. That's not true.

[00:56:36] Leigh Gilmore: #MeToo is a quote, it's a quote from the work of Tarana Burke. And you can draw a line, as I do in the book, from Harriet Jacobs and the book incidents in the Life of a Slave girl, a slave narrative that ties together sexual violence and racial violence under white supremacy and slavery. You can connect that to Toronto Burke. There's a lineage of Black feminist activism in the United States that produced [00:57:00] and propelled the context, the framing, the knowledge, and the understanding that let #MeToo fly.

[00:57:08] Leigh Gilmore: It wasn't just those two words. It wasn't Hollywood, it wasn't Weinstein. It was always bigger than that. And that's why all around the world, longstanding and more recent feminist organizations and feminist movements everywhere on the globe, grabbed #MeToo as a resurgent energy and it wasn't brand new, it was resurgent.

[00:57:33] Leigh Gilmore: So organizations that were doing this kind of work affiliated themselves with this global phenomenon. In a sense, it wasn't an unprecedented moment, although it's important to note that unprecedented is the right word for how it felt. Powerful men were being held accountable. I think a lot of people thought that's new. That piece, that does feel new.

[00:57:57] Leigh Gilmore: So it became, instead of this, you know, like a [00:58:00] brand new experience, it was an episode in a longstanding tradition of intersectional feminist activism and in narrative activism. Because the signature form of #MeToo is the story. It's the personal story. And that is part of a long tradition. And the conditions for that story being heard and heard in new ways is now part of, whatever #MeToo can do and can be going forward, that's part of it.

[00:58:29] Sarey Ruden: That's a wonderful, um, place to kind of wrap this up because I think the intersectionality that allowed the #MeToo movement to get to where it is, the reason that it's there, it's this lineage, as you mentioned. It's not just something that happened out of nowhere. And I think your book, The #MeToo Effect really did an amazing job in educating me.

[00:58:48] Sarey Ruden: I loved reading the literary lineage and the talk about narrative activism is just, it was a really powerful book and an important read, and I really hope that people who are listening will definitely [00:59:00] get this book, The #MeToo Effect: What Happens When We Believe Women by Leigh Gilmore.

[00:59:04] Leigh Gilmore: One of the great joys of this work has been sharing it with audiences, academic audiences and audiences who do work on behalf of survivors. That's been a real joy to be able to equip those who are looking for a different way to understand this problem with some perspective that they may not readily have, but I hope can readily use and absorb. Thank

[00:59:29] Sarey Ruden: Thank you so much. This book is a wonderful tool and we're so lucky to have you. I'm really thrilled that I gotta speak with you. Um,

[00:59:36] Leigh Gilmore: Thank you Sarey, and thank you for your work too. And thank you for including me on the podcast. I appreciate it.

[00:59:42] Sarey Ruden: Course, of course. It's gonna be a great episode.

[00:59:44] Section: Outro

[00:59:44] Anna Stoecklein: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one woman operation run by me, Anna Stoecklein. So if you enjoy listening and want to help me on this mission of adding woman's perspective to mankind's story, be sure to share with a friend. One mention goes a [01:00:00] long way. Hit that subscribe button so you never miss an episode and make sure to rate and review the podcast while you're there.

[01:00:07] Anna Stoecklein: For more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes, follow The Story of Woman on your social media platforms. And for access to bonus content, ad free listening, or to have your personal message read at the end of every episode, consider becoming a patron of the podcast. Or you can buy me a one time metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs and helps me continue to put out more and better episodes. In exchange, you'll receive my eternal gratitude and a good night's sleep knowing you're helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.