[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Anna Stoecklein: Welcome to Season 3 of The Story of Woman. I'm your host, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:00:05] Anna Stoecklein: From the intricacies of the economy and healthcare to the nuances of workplace bias and gender roles, each episode of this season features interviews with thought leaders who provide fresh perspectives on critical global issues, all through the female gaze.

[00:00:20] Anna Stoecklein: But this podcast isn't just about women's stories. It's about rewriting our collective story to be more inclusive, equitable, and effective in driving change. It's about changing the current story of mankind to the much more complete story of humankind.

[00:00:42] Section: Episode level introduction

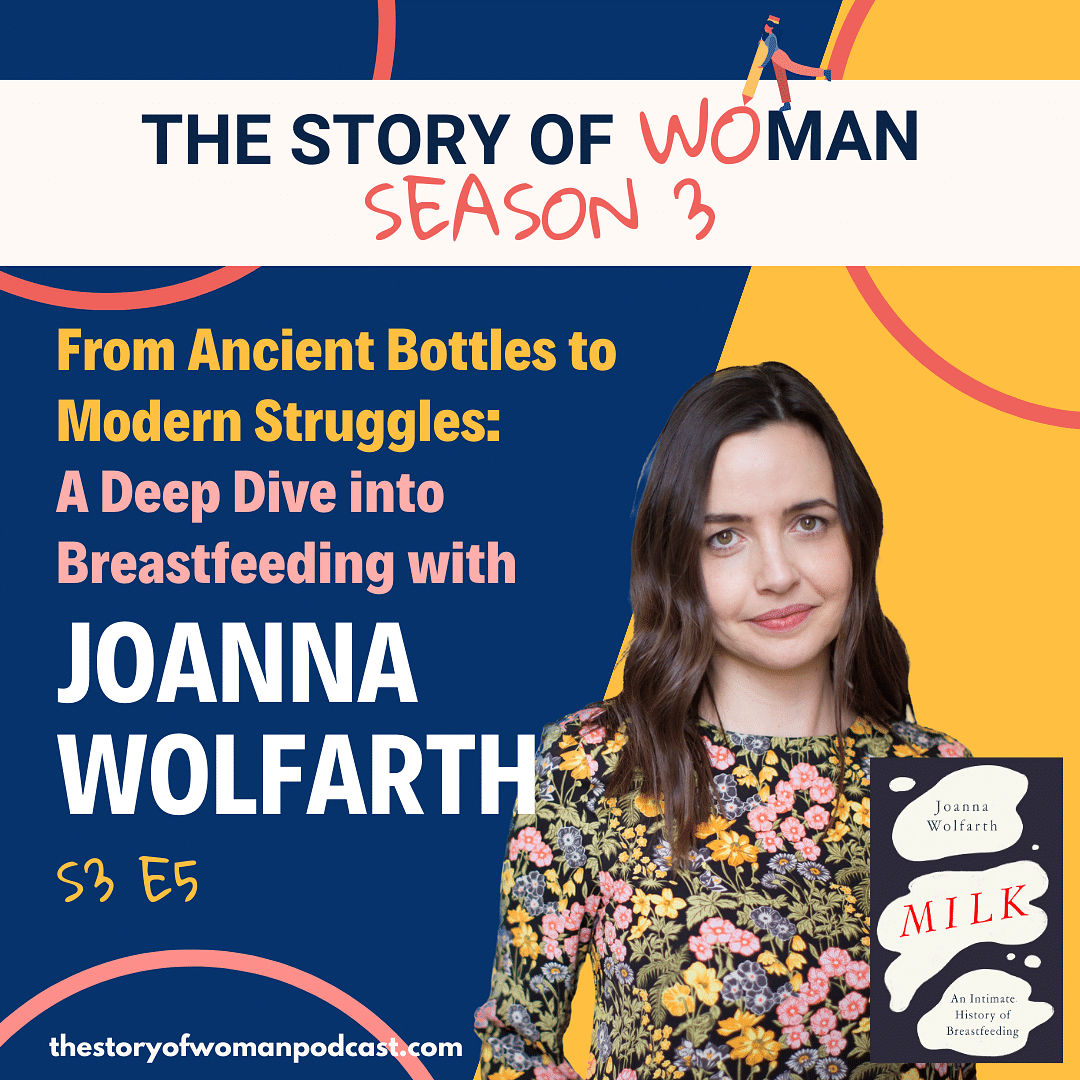

[00:00:44] Anna Stoecklein: Hello, friends, and welcome back. Thank you, as always, for being here. Today, we are diving into a topic that holds a pretty big significance in the lives of all human beings: breast milk. [00:01:00] I'm thrilled to be speaking with Joanna Wolfarth, author of Milk: An Intimate History of Breastfeeding.

[00:01:06] Anna Stoecklein: And just like how Joanna's book is not just for mothers or parents or people who want to become parents, neither is this conversation. Believe it or not, uh, as you'll soon hear, how we feed our babies and the experiences of the caregivers who feed all of the world's babies matters to us all.

[00:01:25] Anna Stoecklein: We'll kick off the conversation with a quick biology lesson, because of course, as seems to be a theme with women's health, there is not very much research into this topic, even though it's growing, so there's a lot of stuff that most of us don't know.

[00:01:42] Anna Stoecklein: So for example, did you know that there's a back and forth dialogue that happens between the baby and the mom, the baby's immune system and needs, and then the milk that the body produces in response to that? I had no idea. And there's a few other tidbits like that, so be prepared to [00:02:00] be amazed by the wonders of the human body.

[00:02:03] Anna Stoecklein: And we'll also get into motherhood as a social construct and all the different ways the idea of what being a quote "good mother" has changed throughout time and how breastfeeding ties into all of this.

[00:02:16] Anna Stoecklein: And we'll reflect on how we arrived at our current situation. One where women who struggle with breastfeeding or choose not to often face judgment and shame. And one where breastfeeding in public is somehow still up for debate. Even though, I mean, among other reasons that it shouldn't be, uh, these same public spaces are often lacking the facilities a woman might need to feed her child in private in the first place.Uh, Stay tuned to hear what percentage of the UK population thinks breastfeeding in public is wrong and even prefers babies to be fed in restrooms rather than at restaurant tables.

[00:02:59] Anna Stoecklein: Joanna [00:03:00] Wolfarth is a writer, cultural historian, and lecturer. She's a specialist in Southeast Asian art history and currently teaches at Open University.

[00:03:09] Anna Stoecklein: And lastly, I want to give a quick shout out to Kulani Jenkins, who is my assistant producer on this episode, the first one of those for The Story of Woman, which is very exciting. And she has been incredible to work with on this. So thank you so much Kulani.

[00:03:26] Anna Stoecklein: If you like what you hear today, please, please take a minute to rate and review wherever you listen and don't forget to follow The Story of Woman on social media, where you can find clips from the interviews and much more. But for now, without further ado, please enjoy this enlightening conversation with Joanna Wolfarth.

[00:03:47] Section: Episode interview

[00:03:48] Anna Stoecklein: Hello, Joanna. Welcome. Thank you so much for being here today. I'm really looking forward to our conversation.

[00:03:54] Joanna Wolfarth: Thank you so much for having me. I can't wait.

[00:03:56] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, so we're talking today [00:04:00] about your new book, Milk: An Intimate History of Breastfeeding, and I wanna start with a story of how you arrived to the point writing this book and a little bit about what it's about. Because I imagine, you know, there might be two camps of listeners, one who hears this and says, oh yes, this has to do with women and women's bodies and reproductive care. Of course there's gonna be a big story here and a lot of history to tell that leads us to where we are today.

[00:04:29] Anna Stoecklein: And there might be others who are thinking, well, this is just a, an innate part of the human experience. The human condition. And it always has been. So what could we even be talking about today? So I'd love to dive in with your personal story that kind of led to all of the research and, in turn, this book, and then we can get into some of the history itself.

[00:04:50] Joanna Wolfarth: Sure. Well, I mean both of those listener camps would be kind of absolutely correct many ways. And I think makes this subject [00:05:00] so interesting. I think also there will be another segment of people who feel that this is not a topic that is, you know, applicable to them.

[00:05:10] Joanna Wolfarth: Often, usually that's men, of course who would probably not pick up this book in a bookstore, unfortunately. But like you said, it is something of an innate condition of humanity. Breast milk is humanity's first food. And we were all babies once and once upon a time we were fed.

[00:05:29] Joanna Wolfarth: And I wanted to explore those ways that we may have been fed and the different experiences and feelings that our caregivers may have felt while they were feeding us. So this book came to me very, very early on in my own parenthood experience. I always knew that I would breastfeed if I ever had children, it wasn't something I thought about particularly, but, my own mother had breastfed us.[00:06:00] And I just came from a family of breastfeeders and it, it seemed like the easy option. It seemed like the free option.

[00:06:07] Joanna Wolfarth: So, you know, of course that's what I was going to do. And then of course, the reality of having a baby, and for many parents, breastfeeding is trouble free, but for others it can take a while to get the hang of it. You and the baby are learning a new skill. It's a new relationship between you and your baby. There can be other issues that arise. And, you know, we experienced, those issues.

[00:06:32] Joanna Wolfarth: So my son, at about four weeks old, went back into hospital because he'd lost quite a lot of weight I thought breastfeeding had been going well and clearly it hadn't. Because now I look back and think, thank goodness it was just a problem with feeding. You know, it was easily remedied with some formula and a breast pump, and it wasn't anything more serious. But at the time it was devastating.

[00:06:56] Joanna Wolfarth: You know, my body had let me down. I had let my son [00:07:00] down, and I was wrestling with all of this, and wrestling with all these images of breastfeeding I'd seen as an art historian. And I thought, I need to write about this. If only for myself, I need to grapple with all of these emotions and all of these feelings.

[00:07:16] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. And we'll, dive into everything that you discovered on your journey because as you point out in the book, because this is innate, as we mentioned, this is seen as natural, sometimes that's a synonym, synonym that's used for easy. And then when it doesn't come easy, these other feelings of feeling unnatural somehow, feeling like you're failing. You know, I think this is quite a common experience. And you point this out early in on in the book, so I wanna point it out early on in our conversation that mothering is not restricted to a gestational or birthing body, and that it must also include trans and non-binary parents as well as adoptive parents. So I just wanna take a moment to highlight that and to see if you can elaborate on that point at all for us, so we have that same understanding moving into [00:08:00] this conversation.

[00:08:01] Joanna Wolfarth: Absolutely. I wanted to make it very clear early on that when I'm talking about mothering broadly, sometimes in the book that is a synonym for caregiving or a parent. Sometimes it's not, if I'm referring to myself, but also in the course of my research, you realize that across histories in certain cultures ideas of gender are different.

[00:08:22] Joanna Wolfarth: And gender expression becomes different and the number of genders is different. And so I wanted to highlight the, the way in which the term mother, historically, and within different cultures doesn't necessarily refer to the person who gave birth to the child. And I believe that that's true now as well, today.

[00:08:42] Joanna Wolfarth: So, you know, that's important as well. And I can point to interesting stories around people, women who have induced lactation, even though they didn't give birth to their child, but they breastfed their child. So breastfeeding doesn't follow that you have to give birth to the child to [00:09:00] then breastfeed the child.

[00:09:01] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. Yeah. And it's a great point to bring up upfront, you know, this social construction of gender, which the listeners of this podcast will be familiar with. And that stems into the social construction of motherhood itself, which we will get into very shortly. But before we do, I thought we'd do a quick biology lesson to start. Because early on in the book, you recall your surprise when quote, "swollen and ready for birth, I first tried to express milk by hand and found that the nipples didn't have just one outlet, but like a garden hose, instead, a thick fluid appears as if from a sprinkler."

[00:09:41] Anna Stoecklein: And I will not lie to you as a non -mother, never having breastfed myself, this was complete news to me as well. And I even trained to be a nurse. I even have worked in the healthcare field and do not remember this ever coming up in the lessons. And I was like, holy shit, is that how it works? [00:10:00] So would you mind briefly explaining to us, how milk production in the body works and then yeah, what do you think the implications are for us as individuals and as a society that we know so little about even just this basic part of such a life giving physiological process?

[00:10:20] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah, it's so surprising, isn't it? But also, you know, really unsurprising, I think to the, the extent to which we don't know our own bodies. Or, you know, our own bodies have not been kind of, I mean, it's common knowledge, isn't it, across the medical world and medical science, the neglect around thinking about female bodies. So that was definitely a surprise to me.

[00:10:41] Joanna Wolfarth: So, historically breast milk was thought to be menstrual blood. And so from the time of the ancient Greeks right through, up until the early modern period, there was a belief that as menstruation stops during pregnancy, [00:11:00] what happens is that there's a vein that connected the uterus to the breasts, and the menstrual blood would come from the uterus, up this special vein and the body's heat and various other things would, would change it into breast milk.

[00:11:14] Joanna Wolfarth: There was a lot of then kind of symbolic and metaphorical connections between menstrual blood and breast milk and a lot of taboos that connected the two, as you can imagine, taboos around blood um, and menstrual blood. What we actually know now is that breast milk works on a supply and demand basis. And so when you are close to giving birth or after birth, your body produces a hormone called prolactin. And that prompts the little ducts in your breast tissue to take all of the kind of fat and sugars and proteins and things from your blood supply and make it into milk.

[00:11:54] Joanna Wolfarth: And then the milk obviously then comes out. And so there's a lot of involvement of [00:12:00] hormones, of prolactin, of oxytocin, that lovely love hormone that can be released when you're giving birth. So breast milk is still made through the blood, but we now have a much better understanding of actually how that process works and that there is no magical vein, that connects the uterus is to the breast.

[00:12:16] Anna Stoecklein: We do know much better of how it works, however, I am gonna point out one thing you point out in your book, which was both exactly as you say, surprising and not surprising at all, which is that we have more scientific research on tomatoes than we do breast milk. This is from your book, so a search of the most comprehensive scholarly database, Web of Science, found 10,000 scholarly articles relating to tomatoes, but only 3,636 relating to breast milk. And it gets better semen brings up 7,851 articles and menstrual [00:13:00] blood just 239. That could not be a better example of, I guess, how we prioritize things in society as it stands. Tomatoes and breast milk.

[00:13:13] Joanna Wolfarth: And again, it's something that when I was doing the research and you look historically, there is so much around, breast milk obviously was known to be, you know, good for babies, but also it has such symbolic potential.

[00:13:26] Joanna Wolfarth: So breast milk often becomes a metaphor within the Christian Church for example. And so on. So it's known to be this magical substance really early on. I mean, even the ancient Greeks talk about how the stars, the constellation, the Milky Way comes from divine breast milk.

[00:13:43] Joanna Wolfarth: So there's always been that level of knowledge, but in terms of actually, what we would now call scientific research into it, that's something that has been a much more recent, development. And historically there was far less research into breast milk and so on, compared to men's [00:14:00] secretions and tomatoes. And so we know now that breast milk is a living substance. It has loads of things to support the microbiome and things like that. So it's an incredible substance.

[00:14:12] Anna Stoecklein: It is. Again, I was, blown away. Not just by the mechanics of it, but by, yeah, the actual composition. You know, you wrote about how when breast milk interacts with a baby's saliva, it secretes antibacterial compounds that can fight against different harmful bacterias like salmonella. I had no idea there there's a back and forth interaction.

[00:14:33] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah. And the specifics, I think of how that interaction works, the mechanisms of that is something that is being explored. And I think the saliva feedback is one theory. But there is definitely a dialogue happening between the baby's immune system and needs, and then the milk that the body then produces in response to that.

[00:14:52] Joanna Wolfarth: Similarly, the hormone levels and the composition of milk may change. It may change depending on the time of day. There's gonna be more [00:15:00] melatonin in the breast milk, towards the end of the day to promote sleep. Haha. Uh, no. None of that necessarily works. Um, um, but also it might vary depending on whether it's your first baby or your second baby, the sex of the baby. There's loads of different ways, it's such a responsive substance.

[00:15:19] Anna Stoecklein: The feedback, the back and forth, I think, yeah, that's, it's incredible and I really look forward to more research continuing onward to see what else we find out as that number, hopefully one day passes the number of tomato articles. But in summary, it is a quite miraculous, magical substance, and that's kind of what's going on inside of our bodies.

[00:15:42] Anna Stoecklein: But what you look at a lot and what we're gonna really focus the conversation on today is what's happening outside of our bodies. And you write early on in the book that we can't talk about breastfeeding without understanding that motherhood is a social construct. Just what we touched upon in the beginning.

[00:15:59] Anna Stoecklein: And [00:16:00] then throughout the book you talk about all the different ways, socioeconomics, scientific, political, all these different ways of the ideas of what a good mother is, has been kind of constructed and deconstructed. So can you just kind of help us understand how is motherhood a social construct? And then perhaps before we get into some of the current barriers to breastfeeding, can you walk us through some of the historical examples of how this construct has shaped not just what we think about breastfeeding and motherhood, but how at times it gave us little choice in

[00:16:37] Joanna Wolfarth: Mm, mm-hmm. Yeah, Adrian Rich draws that distinction right between motherhood as the institution, as the social construct, and then mothering as the act, you know, mothering as a verb. And I would say mothering as a verb is something that I would say is non-gender specific.

[00:16:53] Joanna Wolfarth: But motherhood as a kind of institution, as a socially constructed [00:17:00] identity, it's all of those things around what makes a good mother. I think it kind of wraps itself up in a language around, you know, what is natural, what is innate, what good mothers should do, the emotions they should feel, the responses they should feel. It's constructed, I think, around this idea of, it's a very sentimental kind of picture of motherhood. It's about motherhood as kind of self-sacrifice for your child. That if you want to do anything that takes you, that is anything other than being a mother, that's somehow viewed as selfish.

[00:17:34] Joanna Wolfarth: It's the kind of ideas about motherhood that we see play out in discussions around working moms around, stay-at-home dads, around the choice between formula and breastfeeding. Which is something that I think, you know, I'm so glad we have that choice. That there are choices available to parents. But it's about this kind of cultural imposition on us and how we should be in the [00:18:00] world. And it comes with so many value judgments.

[00:18:02] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. I thought that was a really important distinction that you made throughout the book, the motherhood compared to mothering that Adrian Rich and other people have, have pointed out and this is again a quote from your book, "Mother is to nurture. Mother is not a fixed, stable identity. Instead, like love, it is both a noun and a verb. And 'mother work', can be considered doing caring, nurturing, whereas motherhood is a noun in a kind of fixed state of being."

[00:18:31] Anna Stoecklein: I think that really, really helps to kind of paint the picture between the two. So then looking at motherhood and looking at that fixed state, that's kind of a social construct, help us understand, you know, how has this changed throughout time? So we wanna talk about what's going on in the current day, the current barriers and challenges. But I think it's really helpful, as you know, and this is kind of what led you to it, to look back in time and to see how did we get to this, [00:19:00] where we are today. And obviously your book is very comprehensive and it's very dependent on location and time and class and so many different variables. But can you give us a sense of how these messages, these constructs have kind of changed and evolved over time?

[00:19:16] Joanna Wolfarth: Absolutely. I think one of the best, you know, how we feed our children, how we feed our babies is actually, is such a good way of seeing the different ways that motherhood has been constructed. You know, motherhood as a kind of fixed identity of something that is imposed on us from, from kind of outside forces.

[00:19:32] Joanna Wolfarth: So, for example, thinking about wet nursing, right? Who feeds the baby? And of course there is so many questions of class and status and wealth that comes into this. But for so much of history, it wouldn't always have been a birth mother.

[00:19:50] Joanna Wolfarth: Feeding her own child. And that's still true today. It's true of certain cultures, certain societies, where shared feeding [00:20:00] is a kind of completely usual part of child rearing. So if the birth mother has to go and do something else or can't feed her own baby, somebody else within that kinship group will carry out the task. And I know women here in the UK who do that. Although I think it's far less talked about here because we have a construction of motherhood which can view that as quite a taboo thing to do.

[00:20:23] Joanna Wolfarth: But then of course that kind of shared feeding becomes something more formalized in the practice of wet nursing. So we have ancient Babylonian texts, which are contracts which specify the length at which a wet nurse would be employed to feed a baby. The kinds of payments she would get, the kinds of status she would be allowed to have. In Egypt, wet nurses who wet nurse pharaohs were very high status, and the children of the wetness were seen as sort of like kin to the kingship. There was a connection between them. They were kind of milky siblings, or milk kin.[00:21:00]

[00:21:00] Joanna Wolfarth: And then if we look at Europe, you know, having royal babies, aristocratic babies, wealthy families, babies fed by wet nurses because the role of their birth mother was to get back to the business of procreation. So not wanting to be tied up, breastfeeding, wanting to return to fertility, so they can produce more babies. Also there was a belief that sort of in early modern England that sexual intercourse could trouble the breast milk. So it might curdle the breast milk the body gets too excited. Um, so, so, um, if you have the means to employ a wet nurse, then you want to employ a wet nurse so that your wife can return to the marital bed. So there's all these ideas about the role of the woman, the role of the mother, as both a mother and a wife, and the ways in which certain mothering duties were kind of packaged out.

[00:21:59] Joanna Wolfarth: And then[00:22:00] in Western Europe towards the end of the 18th century, there was a kind of change, and there was this idea that actually wet nursing is problematic. One concern that you do see throughout history is that a wet nurse might pass on characteristics of the baby through the milk.

[00:22:19] Joanna Wolfarth: So there were concerns, in the 17th and 18th centuries, that working class women, who are wees might pass on undesirable traits to the children, you know, immoral character. You have wealthier men who start writing about how all of their health misfortunes in adulthood are down to the fact that their wetness wasn't healthy enough or wasn't of a higher social standing. So there's all these concerns around wet nursing.

[00:22:49] Joanna Wolfarth: There was also practical concerns around passing on things like syphilis between a wetness and a child. So there was lots of concerns about wet nursing. And what we see is [00:23:00] philosophers like Jean Jack Rousseau, who famously kind of constructs this idea of we've got to get mankind back to kind of nature.

[00:23:07] Joanna Wolfarth: We've got to restore kind of moral sense of duty amongst men. And the way to do that is birth mothers should feed their own babies. So it's not just a health issue, it's not just about, you know, what's best for baby, it's what's best for the whole of civilization and for the whole of mankind.

[00:23:25] Joanna Wolfarth: And so you then get lots of writing, promoting the importance of a mother feeding her own child. So, wet nursing goes outta fashion. And this idea of the mother as sentimental nurturing, non-sexual, so that distinction between maternity and sexuality starts to come to the fore. And that completely changes how we think about mothers and the mothering role, particularly mothers with their infants.

[00:23:55] Anna Stoecklein: And, um, worth noting, Rousseau, as you point out in your [00:24:00] book, right, was a big advocate, as you say, really had this push for making sure that it's the birth mother that feeds the child. And then where did he send his children?

[00:24:12] Joanna Wolfarth: They all, went to, uh, founding hospitals. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:24:16] Anna Stoecklein: To have wet nurses..

[00:24:17] Joanna Wolfarth: have wet nurses. If they were lucky, the children in the founding hospitals would be sent to wet nurses. Otherwise they would be what was known as, kind of dry fed. So it would be something like a mixture of pap, you know, kind of milky barley bread concoction.

[00:24:31] Joanna Wolfarth: Or they would be fed with animal milk, with goat milk or something. So yes, Rousseau's own children, he certainly was not involved in the day-to-day upbringing. He was barely involved in their upbringing at all. And yeah, he certainly didn't make sure that they were fed, by their birth mother.

[00:24:46] Anna Stoecklein: Which I just feel like that's a little microcosm, a little good example of the people who are coming up with these rules and norms throughout time, and the ones that are actually living them out.

[00:24:59] Joanna Wolfarth: Absolutely, [00:25:00] absolutely.

[00:25:02] Anna Stoecklein: Okay then, so that's a good feel for how it's changed throughout time and in your book, there's this really clear demarcation, I guess you could call it, from the industrialization age to where we get to today. So perhaps could you walk us through some of the biggest changes that occurred around the social norms and what happened with breastfeeding around the time of industrialization?

[00:25:27] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah. I mean, we start to see, I suppose, ideas of time changing, ideas of how we measure our working day, and that becomes by the clock, right, by the minute and the hour. But also in terms of where women were living and working. So we start to see obviously the move to cities and urbanization, which would often take women away from maybe the support that they would have from their community, maybe having, you know, their mothers or their other kind of kinships, support that they would have to help with [00:26:00] child rearing. If women are going out to work in factories, then they're no longer working in the home.

[00:26:06] Joanna Wolfarth: So I kind of, I, it's, it's a big contrast to make, but there is this wonderful sixth century bronze statue that I came across in my research. It's from Indonesia, and it shows a woman sitting on the floor very upright, and she has a foot loom. So she's a weaver. She has her loom at her feet. But she's paused that while she breastfeeds her baby. It's a beautiful image, and we see throughout history where women would've worked within the home, but they would've been able to pause their work to feed their baby or whatever.

[00:26:42] Joanna Wolfarth: But if you're going out to a factory, you can't do that. So there were ways that, ideas around feeding babies to a schedule. So feeding them every three hours, every four hours. Obviously if women were going out to work, then that would perhaps affect their milk supply because it works on a supply and [00:27:00] demand supply and demand basis.

[00:27:02] Joanna Wolfarth: And so, then sometimes that would be detrimental to women's milk supply. They would then supplement feeding with animal milks or pap, which weren't good for the babies and also were delivered in very unhygienic ways. There was no sterilization. So the bottles often dirty and disease ridden.

[00:27:21] Joanna Wolfarth: And then we see that kind of continue in what we see in the early 20th century with the rise of what was known as scientific motherhood and this idea of things needing to be quantifiable. And breastfeeding is, it's sometimes it's really hard to quantify sometimes. You can look at your baby, we can think about baby's weight and so on, but it was a way of trying, I suppose, to kind of put motherhood in a kind of scientific language.

[00:27:50] Joanna Wolfarth: So feeding by the clock, feeding for certain amounts of time, feeding for certain intervals of time. And I think that really, really [00:28:00] changed how we think about our bodies. You know, they become, they become industrial, they become machines. It's more militarized in a certain sense. And I think probably a consequence of that was women becoming more divorced perhaps from their bodies as well, and less trusting of their bodies.

[00:28:17] Anna Stoecklein: Hmm. Yeah. And I'm wondering if we can look at any of this and see how it kind of evolved to some of the barriers that we see today. You know, seeing this division between paid work, women going out and, and working and having this divide, meaning that their breastfeeding bodies, you know, weren't visible like they were before, and then they come across these different barriers that we'll get into. So, yeah, can you tell us about some of the current barriers, to breastfeeding that exist? And if you feel like any of this kind of stems from these problems that you've mentioned, how that's kind of connected?

[00:28:51] Joanna Wolfarth: Well, I think, you know, one problem that we can draw parallels to is the problem of kind of going out and paid work. And so the absolute need [00:29:00] and right for parents to have paid parental leave, I was very fortunate that I'm in the uk so I was entitled to a year from work, and much of that year was paid.

[00:29:12] Joanna Wolfarth: And that I think is absolutely necessary to kind of establish breastfeeding, to establish yourself as a mother or as a caregiver and to be with your baby, if that's what you kind of choose to do and what's right for you. So there has to be, there has to be this investment, right, by governments and by employers to support caregivers and to make sure that they have access to paid leave.

[00:29:39] Joanna Wolfarth: And I think this idea that it's kind of, that it's natural, that it's free, that it's easy, I think it's a, you know, it can be a way of putting all of the responsibility on the individual woman, on the individual parent without looking at the broader connections, without saying, well, we need structural support, we need financial [00:30:00] investment, we need all of those things.

[00:30:02] Joanna Wolfarth: When you look back at history, women would be mothering in communities with structural support around them. And I think that is something that is missing now. And something that we need And I think that does come from the idea of the industrial kind of women's body, right, that does this because it's innate, because it's natural, and therefore doesn't need any external support or external help.

[00:30:29] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. Yet these, quote unquote, natural work that is being done still has to exist within these systems and structures. And because of that, as you say, then it's gonna be, especially particularly groups of people that suffer, people that are already left out of these systems, marginalized within these systems. So yeah, anything that you can talk to about how these barriers impact particularly along class and racial lines?

[00:30:56] Joanna Wolfarth: Mm, mm-hmm. Yeah, I mean, breastfeeding, I said right at the beginning that it's [00:31:00] free and it's only free if you don't value women's like labor, you know? But yes there are different intersections of, of class, of race, and it that's very, very different I think within a UK context compared to a North American context and to the context within the us. There's very different histories there. There's very different histories along racial lines in terms of mothering and parenting and the legacies of enslavement still lingering. So that there's, there's real kind of differences I think, within the different contexts.

[00:31:35] Joanna Wolfarth: Here in the uk, which I'm much more familiar with, it's interesting that actually breastfeeding, over the last kind of 50 years has been kind of more prevalent and more supported within, black and Asian communities. Where there often is more kind of family support.

[00:31:55] Joanna Wolfarth: And it's seen as the done thing. I was talking to someone quite recently, about, in the [00:32:00] 1960s, 1970s, 1980s in the uk where breastfeeding rates were quite low because formula was seen as the best thing for your baby and it was seen as something, you know, you can afford to buy formula, that's it was a status symbol.

[00:32:13] Joanna Wolfarth: And actually women in, cities in the north of England, where there was big communities from the Asian subcontinent would often feed their babies' formula in public, but breastfeed them at home. Because breastfeeding is what they felt supported in doing and what they wanted to do within their community.

[00:32:29] Joanna Wolfarth: But they felt a broader pressure to look like a good mom and a good parent and doing the best by using formula. So there's so many different points of intersection and where those ideas of what being a good mom, where they come from and where they are imposed from, and also the legacies and the baggage that we all carry within us.

[00:32:51] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. Um, and I appreciate you sharing all of that background. I'm happy to jump in here real quick on the American side and go on a, a [00:33:00] quick tangent about the disparities there. Um, because yeah, I've just got some stuff written down here cuz, as, as an American, as someone who has been speaking about everything going on there in terms of Roe being overturned and lack of healthcare and all of that, that all of this just feeds into that dire picture and situation that inevitably impacts marginalized communities more than anyone. But you know, in America, speaking of that healthcare, there is no universal healthcare and no family pay leave. Zero days!

[00:33:38] Joanna Wolfarth: I am aware of this and I see, you know, I, I hear stories of people having to go back to work two weeks after giving birth, and I just cannot wrap my head around how that is possible in any way. I find it, yeah, it is, it is deeply disturbing. Deeply disturbing.[00:34:00]

[00:34:00] Anna Stoecklein: Two weeks. And I had, um, Reshma Saujani on here in the last season who has an organization that's advocating for policies for paid leave and for more support. And she told two stories. And one was of a woman who was literally in labor trying to get an email across the line on her laptop because she needed, or, you know, an email, a document, whatever, it doesn't matter on her laptop, working on something that needed to be done by midnight or else she wouldn't qualify for her leave. And she's literally in active labor.

[00:34:30] Anna Stoecklein: And the other story she told was of exactly as you say, two weeks back. And it was a NICU nurse, so it as a nurse going back to take care of other people's newborns two weeks after having their own. And it's just, it's awful. And then, you know, on top of that, without the leave, without the healthcare, low wage workers, who are often people of color, left completely on their own to navigate this whole postpartum period, deciding if they can afford time off or not, figuring out if they [00:35:00] can afford formula so that they can go back to work on top of childcare.

[00:35:06] Anna Stoecklein: And then you look down at the breakdown in America, again, this is in America, where hospitals that serve larger Black populations are less likely to offer help in support in breastfeeding and are more likely to introduce formula. Black babies are much more likely to be born prematurely. So in 2019, 14% of Black mothers gave birth prematurely compared to 9% of white mothers.

[00:35:28] Anna Stoecklein: And all of this is a huge barrier to breastfeeding. And again, in communities of color, there's kind of deserts for support groups and lactation services. And then as you've mentioned, you can't touch upon any of this without talking about the generational trauma that exists, undoubtedly exists within Black bodies from the forced wet nursing and . The enslavement. So yeah, it's, it's dire there, especially.

[00:35:55] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah. And I mean, you know, things in the UK obviously we have, [00:36:00] across the board rights to leave rights to maternity pay, if you qualify, rights, you know, free healthcare, access to those kinds of things and support. But I have to say you know, we have our issues here with recent reports, the embrace report, which looked at health outcomes for Black and brown women who are more likely to die in the first, of the per, well within the perinatal period.

[00:36:24] Joanna Wolfarth: And so we have huge disparities here, yeah, yeah. And problems with the sort of, the institutional racism and problems within, maternal healthcare here as well.

[00:36:33] Joanna Wolfarth: And it's something that I wanted to be very careful about talking about in my book around the question of formula that you brought up. And it becomes a very pertinent question when we are thinking about women going back to work or women choosing, saying, breastfeeding's just not the right option for me. In thinking about formula, I realized that for much of my life I've conflated the formula industry and the marketing formula with the productive formula.

[00:36:55] Joanna Wolfarth: And I think doing the research, I'm so [00:37:00] grateful that we have formula, that we are aware of Hygiene and sterilization and that we have lovely bottles that are not made of glass they used to be. But you know, I think the fact that access to formula, I think, you know, it's a health product.

[00:37:15] Joanna Wolfarth: It should be something that is not something that has to be paid for, that is not something that, that is a commercial product. And we've seen the problems over here with the cost of living crisis, issues around parents being able to afford to buy formula and then having to kind of water it down or not use sufficient quantities of it, which again, is deeply disturbing and completely immoral as a society that parents are forced to do that.

[00:37:42] Joanna Wolfarth: And that aren't able to access the formula they need. And then obviously in North America with the shortages of formula and those kind of supply issues and problems with that. And it shows how deeply connected how we feed our babies is to so many other intersections of society. And you talked about kind of reproductive [00:38:00] rights as well, and I think that's very important to draw those parallels.

[00:38:03] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Absolutely. And yeah, thank you for bringing all that up with formulas. That's all really, really good points. And before we get into the future, where we go from here, the learnings, there's one more problem I want to, uh, bring up, because I can't not read this sentence from your book, because again, it's one of those surprising, unsurprising. And this has to do with the perception of breastfeeding in public.

[00:38:33] Anna Stoecklein: "At least a third of the UK population thinks breastfeeding in public is wrong, and more people think it's preferable for a baby to be fed in a toilet than at a table in a restaurant."

[00:38:46] Anna Stoecklein: In a toilet! People prefer a woman to do this in a toilet than in public. And I just, yeah. One, I'm purposefully saying that slowly to let it all sink in, even though [00:39:00] listeners will be unsurprised about this. But I'd love to just hear, I don't know your thoughts on it and also if from all of your research and anything there's any way to help us understand why people are so repulsed at something that they also see as incredibly natural and beautiful and all the other things...

[00:39:20] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah.

[00:39:20] Anna Stoecklein: ...how do we hold these two?

[00:39:21] Joanna Wolfarth: Right. Yeah. This is the, this is the kind of the bind that we exist within. And not only I think around breastfeeding and breast milk, but also just experiences as women in the world, we are kind of always caught in that bind. And our bodies being viewed as disgusting or abject for doing things that they, they do.

[00:39:41] Joanna Wolfarth: But yes, so yeah, breastfeeding in public, still something that is kind of up for debate, you know, in the UK we have laws protecting somebody's right to breastfeed in a public space or in restaurant or in public transport. Yet still there is a newspaper article after newspaper [00:40:00] article of women being asked to cover up, women being asked to leave.

[00:40:04] Joanna Wolfarth: There was a story quite recently in a museum in Cambridge where a woman was asked not to feed. She was sitting in a gallery space not to feed because there was no food or drink allowed in the, in the museum or something.

[00:40:17] Anna Stoecklein: I saw that!

[00:40:18] Joanna Wolfarth: It happens, it's just, it's just this ongoing issue. And so when you become a parent yourself, you know, I remember feeling so anxious about feeding in public for the first time. And every time I did thereafter, always being on, you know, kind of high alert of like, is this the time that I'm gonna be asked to leave? Is this the moment where I can get out some of the like self-righteous anger that I have by telling somebody that actually, my baby's hungry, I'm gonna feed my baby.

[00:40:43] Joanna Wolfarth: Um, but, I think it goes back to this idea that, many people view it preferable for us to breastfeed in a toilet because somehow breast milk is some kind of contagion. And I've seen people making[00:41:00] the comparison saying, well, I wouldn't urinate in public, or I wouldn't, you know, you know, I wouldn't defecate in a swimming pool, you know, and so making. Because it's a bodily fluid, right? And so, and again, you're being trapped in that it's the best thing you can do for your baby. That narrative that gets really pushed on you. And at the same time, we don't wanna see it. Don't you dare leak, make sure you've got your breast pads in. We do not wanna see your baby feeding.

[00:41:28] Joanna Wolfarth: We don't wanna think about it because it's also disgusting. And that plays out historically as well. As I said earlier, you know, this idea that breast milk was menstrual blood transformed. So it was seen as having this kind of holy, divine potential. It was good stuff. It's magical stuff, but it's also a bodily fluid from a woman's body. Therefore it is abject, it is disgusting, we don't wanna think about our bodies leaking. I think there's also something about the intimacy of the [00:42:00] act between a mother and child that some people can find discomforting. And then of course, as I said, this distinction between the maternal and the sexual and this confusion we have over the breast.

[00:42:11] Joanna Wolfarth: And many people do not want to be confronted with the possibility that a breast can be sexual and maternal, sometimes at the same time. That poses a real problem, I think for us culturally.

[00:42:23] Anna Stoecklein: So how do we move forward beyond this? I mean, I wanna ask you about some of the specific things that you found in your historical search, but you know, I guess just more pointedly, do you have any ideas, do you have any thoughts about how we overcome the stigma and how we move into the next generation, not just evolving to a different, I mean, it's always gonna be a social construct, right? That that's gonna be hard to get rid of. But the type of construct where it's more aligned with an authentic [00:43:00] experience for that individual person and less at the will of the collective society, politics, science, and, and all of that.

[00:43:08] Joanna Wolfarth: Yeah, I mean, I think one of the first things is to do what you do on this podcast, for example, and to keep telling stories and to keep talking about these things. And I always said very early on with this book that, I think one of the things when you are writing on issues, sort of women's issues, which are viewed as niche subjects, quite often there is a kind of view of, well, we don't need any more books on breastfeeding, because now we've got a book on breastfeeding.

[00:43:35] Joanna Wolfarth: Well, no, we have one book and oh, well, there's lots of books, but you know, there's not enough and there needs to be more, and there needs to be more written by, you know, across the board of a diversity of voices. And so we can really interrogate what that experience is. I think for so long there's been this kind of tyranny, for women to kind of just get on with it, to not talk about these [00:44:00] experiences, to not share them because somehow it could be seen as maybe that it detracts from the love that you have from your child if you talk about the difficulties maybe of it or, you know, people don't wanna hear about it or whatever.

[00:44:12] Joanna Wolfarth: And so I think we have to just keep telling our different stories, trying to connect to the past, trying to say that it intersects across so many different kind of points of class, race, gender, sexuality, those kind of things. But it also intersects with other issues around reproductive rights, issues of women in public space.

[00:44:35] Joanna Wolfarth: Because I write and I think a lot about, we talk about feeding in public, for example, and I realized when I was breastfeeding in public, I was breastfeeding in public for the first time as a mother, but I was bringing with me all of this baggage, 35 years of being a woman in the public sphere, in public space where we know we're being scrutinized. We know we're constantly being objectified. We know that we are not safe. We [00:45:00] are catcalled when we are 12 years old in our school uniform. You know, and that continues. And breastfeeding in public feeds into that conversation as well of just what it is to be a non cis male in the public sphere.

[00:45:16] Joanna Wolfarth: I wish that there was an easy answer to it all, but I think it is just about pointing out these things, challenging them, trying to work together and say, this isn't just an issue for women with babies. It's a bigger issue and it's an issue that society should care about. And actually that has economic benefits as well because, you know, we talk about the lack of government investment, the lack of support and help available to new parents. But, breastfeeding has a huge economic value.

[00:45:46] Joanna Wolfarth: The Wealth Health Organization estimates that every $1 invested in supporting breastfeeding yields $35 in economic benefits. So $1, $35 in benefits. [00:46:00] Now, I would hate for that kind of to be taken to create a world where all women now have to breastfeed their babies. For the good of the economics or whatever. Women should have a choice.

[00:46:14] Joanna Wolfarth: And thank God that we do have choice in how we feed our children. But the onus should not be put on the individual parent. It is something structural and it's something that society needs to care about more broadly.

[00:46:26] Anna Stoecklein: Which is again, just a recurring theme with absolutely everything that we talk about on this podcast. Don't blame the woman. It's not the woman's job to fix it. Gotta zoom out. Gotta look at the structures and systems and, and similarly, don't look at necessarily the individual man. Look at the systems and structures and all the way around.

[00:46:46] Anna Stoecklein: So stories and everything that you've laid out. And not to take us too far back since we've already kind of gone back in time, but you know, in all of your looking back in history and in art, I'm [00:47:00] wondering if there's anything that you learned that you feel we can all learn from what you found from the ancient ceramic bottles and the Greek mythology and the Victorian nipple shields and everything else.

[00:47:13] Joanna Wolfarth: I mean, all of that was revelatory to me. Victorian nipple shields made of tin and ivory. Baby bottles made of, you know, beautiful glass. But in the Victorian period they were told you only have to wash the tea t every three weeks. And you're like, ugh, that's disgusting. The baby bottles was something that just really, I, because I was writing this book whilst I was breastfeeding, so I was going through it whilst I was working on the book. And so I was dealing with my own very kind of difficult and mixed feelings around bottle feeding my own son and how that made me feel about myself and as a good mother in the, this institution of motherhood and all of those things.

[00:47:57] Joanna Wolfarth: And then I came across um, ceramic baby [00:48:00] bottles that started appearing, the earliest examples about 7,000 years old in Europe. And recent studies have looked at these bottles and found that they actually contain traces of animal milk and human milk. Now, these bottles were found in infant graves. Is that just because that's where archeologists dig, so that's where we find the evidence? Or was this an act of giving these babies something for the afterlife? It made me think about the nurturing and the care and the nourishing, and how deep those feelings are.

[00:48:35] Joanna Wolfarth: And I felt connected to this parent 7,000 years ago. Maybe they'd fed their baby, you know, maybe they were using bottles to, they probably were using bottles actually, to kind of wean slightly older babies and infants. So they were certainly using bottles for babies, but also just that sense of deep care and love and the kind of universality of that really rung tree.

[00:48:55] Joanna Wolfarth: It made me feel much less alone in my new motherhood. It made me look [00:49:00] at my own bottles drying on the kitchen worktop in a very, very different light. And it just connected me to something bigger. And I think that was the kind of most valuable part of that research.

[00:49:10] Anna Stoecklein: I really, really love that. That's kind of the question I wanted to start to end on is this, yeah, what you kind of invoke throughout the book, this idea of us being woven together through time and space. And I just wanna read a couple lines. I was gonna pick one, but they're all good. So I'm gonna read a few of them, that really pull out this idea.

[00:49:29] Anna Stoecklein: So you wrote, "There may have been nice when we felt alone, but we were always stitched together into a vast and elaborate tapestry. Single threads can be fragile but when woven together, a textile is strong."

[00:49:43] Anna Stoecklein: And then you also said that you keep coming back to this idea of threads and weaving "as if trying to construct something bigger out of my own experience" exactly as you just said, "Because milk, in whichever way it is to be delivered, is the white ink that writes our origin stories, which binds us all [00:50:00] together generation after generation, woman with woman, generation with generation."

[00:50:05] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely love that. Think it's so beautiful and really goes to show the power that we have, exactly as you point out, single threads can be fragile, but when woven together, a textile is strong. So, kind of a two-part question because you talk a lot about the politics of milk and you know, we've really, we have gotten into that a bit today, but one thing that you mention is mothering s potential as a destabilizing threat to patriarchal domination.

[00:50:37] Anna Stoecklein: We've talked a lot about how politics and social norms and all of this kind of influence mothering and the way we see breastfeeding. But I'm wondering if you can talk to that point of why you think mothering is seen as such a threat. Is it because these single threads when woven together are so strong? Is it because of, of that or what your kind of thoughts is there, and then the community [00:51:00] aspect and how you see us as powerful because of that interwoven connection.

[00:51:05] Joanna Wolfarth: Mm mm I think there's a number of ways it can be destabilizing. I think in one sense it comes back to that idea of woven together with stronger. And I think it's very evident to me that patriarchy fears the power that we have, in the way that they work so hard to divide us.

[00:51:25] Joanna Wolfarth: And we've talked a lot about breastfeeding and we've talked about formula and we've talked about the different ways that those choices we make, when we are lucky enough to have choices, cuz I realize that, you know, for some people formula is not a choice or breastfeeding is not a choice. But the fact of how we feed our children is often used as a way of dividing us, right, as if we're gonna be in camps and, you know, the breastfeeding mom is gonna judge the formula feeding mom or the bottle feeding mom is gonna judge the breastfeeding mom in public.

[00:51:53] Joanna Wolfarth: And when you talk to women, and I've talked to many, many, mothers and non-binary parents, as part of the research for [00:52:00] this book, you realize that that fear of being judged and that fear that another parent might think you are judging them is so prevalent. And I think that it is a tool used to divide us, right. But I think the reality is, that actually, if we all came together and said like, it doesn't matter how you fed your baby. You did it your way. I'm doing it my way. We need to come together to support each other. We need that community, that word that you, you did bring up, to demand better, I think the patriarchy fears us, and I think we can see how they fear us, and you can see it over history in the way that they try to control us, that they try to dominate our bodies, take away our bodily control, configure our bodies in the cultural realm as something that is disgusting.

[00:52:50] Joanna Wolfarth: And you see it playing out in kind of horror movies and, and all sorts where the lactating body is like the most abject, disgusting thing. Or asking a grown [00:53:00] adult to try breast milk is seen as such a squeamish taboo thing. I think trying to reclaim our bodies and saying, actually there is a sense of abundance in all of this in the way that the fluids that our bodies produce. There is abundance and potential. And I think that is the destabilizing force is that creative potential. And I mean, creative in a very, very broad sense. I don't just mean in terms of gestating a baby or whatever. It's really... we have a generative potential.

[00:53:34] Anna Stoecklein: Yes, the interwoven textile. I think that's a really good analogy and a good imagery to imagine us all, you know, when talking about breastfeeding and the way milk connects us, but also just outside of that and when women and when people come together, how much stronger we all are together. So that was a really beautiful something interwoven throughout the whole book.

[00:53:58] Anna Stoecklein: Um, So I'm wondering then just [00:54:00] kinda straightforward talking to the listeners, if there's anyone listening who's perhaps a new mother or may decide to become one one day, anything you might say to them as they begin to navigate this world of breastfeeding?

[00:54:13] Joanna Wolfarth: Mm-hmm. It's, I find this question so challenging because it's so hard to know in retrospect what I would've found helpful. Now I have the benefit of hindsight. But what would I have found helpful at the beginning or, or before? I think just, remember that you are not alone in any of this.

[00:54:31] Joanna Wolfarth: That you are not an isolated being in the world underneath a bell jar. You are connected and the experiences that you have, you can find support for those. There is support, find it and yeah, just kind of do the best. You know, that's, that's kind of it, like find your community somewhere, whether that's online, whether that's in person. But just know that you're not alone in what you're doing and seek support. And that breastfeeding sometimes is just a dance that you have [00:55:00] to learn with your baby because they have to learn how to do it too. And it's a relationship that you are navigating and it can take a little bit of time. So, yeah. Ask for help.

[00:55:09] Anna Stoecklein: Beautiful and you're not alone, and you can also read Joanna's book and discover you're not alone as well, feel connected, not just to those currently but generations past as well.

[00:55:20] Anna Stoecklein: If people One thing away thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:55:25] Joanna Wolfarth: I think that, I would want them to realize that how we feed our babies is something that matters to us all. It matters to humanity. It is not just an issue for people who happen to be parents or who happen to be mothers. As I said at the beginning, we were all babies once.

[00:55:43] Joanna Wolfarth: It is something that intersects across so many different parts of our lives of society, of culture, and I think that, it would probably be very illuminating for men to read more women's stories. So, [00:56:00] um, shameless plug, buy a copy of my book for a man in your life.

[00:56:05] Anna Stoecklein: No shame there. Definitely. I second that. Well, that is an excellent note to end on. Buy a copy for yourself and buy for two men in your life. I'm gonna up the ante there.

[00:56:19] Anna Stoecklein: Joanna, thank you so much for being on today it was an absolute pleasure. Thank you for your work and your book and speaking with you

[00:56:26] Joanna Wolfarth: Thank having me. It's been a pleasure.

[00:56:30] Section: Outro

[00:56:30] Anna Stoecklein: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one woman operation run by me, Anna Stoecklein. So if you enjoy listening and want to help me on this mission of adding woman's perspective to mankind's story, be sure to share with a friend. One mention goes a long way. Hit that subscribe button so you never miss an episode and make sure to rate and review the podcast while you're there.

[00:56:53] Anna Stoecklein: For more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes, follow The Story of Woman on your social media [00:57:00] platforms. And for access to bonus content, ad free listening, or to have your personal message read at the end of every episode, consider becoming a patron of the podcast. Or you can buy me a one time metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs and helps me continue to put out more and better episodes. In exchange, you'll receive my eternal gratitude and a good night's sleep knowing you're helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.